Early Childhood Engagement of CALD Communities Children Young People and Families

Early Childhood Engagement of CALD Communities

Impacts of COVID-19

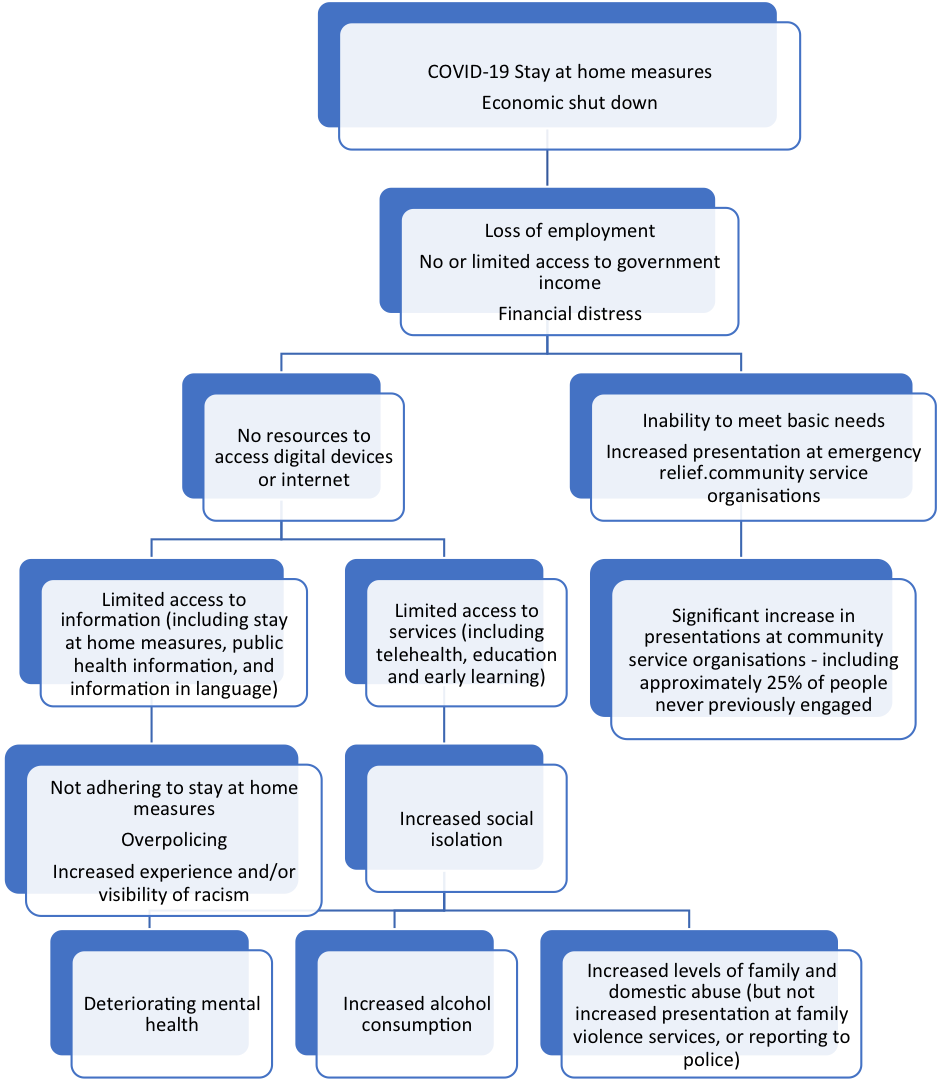

COVID-19 has caused profound social and economic dislocation, with the most vulnerable and disadvantaged Victorians feeling the impacts most acutely. VCOSS members report new and emerging culturally and linguistically diverse communities, including asylum seekers and refugees, are likely to have experienced the impacts of COVID-19 more severely than established culturally diverse communities and the broader population. The reasons are varied and include: difficulties understanding or navigating a range of systems, less established networks of support, and limited English or literacy.

Early childhood education is a key window of development in a child’s life. Two years of high-quality early learning for children who experience disadvantage or vulnerability, including low proficiency in English or being socio-economically disadvantaged, can turn the tide for building strong foundations for later learning and good life outcomes. Many Victorian children had their participation in early childhood education disrupted during the initial COVID-19 response phase. For some children, this disruption was because of economic factors. Measures were instituted by the Victorian and Commonwealth governments, for example, to introduce temporary payment relief, however, as we move into the COVID-safe environment, and relief measures cease, the return to fee-for-service early childhood education and care is a key issue of concern, given that many Victorian families will continue to experience economic hardship through this next stage of the pandemic’s trajectory.

Culturally and linguistically diverse families who experienced heightened vulnerability during COVID-19 should not have their access to a range of early learning restricted by financial barriers.

Many of the recommendations made by VCOSS in its substantive submission are amplified by COVID-19. In particular, COVID-19 highlights the critical need to formally recognise and fund communities for the role they play in providing trusted and accurate information, and the need for greater investment in outreach to ensure families are connected before times of crisis hit.

Key recommendations that are particularly relevant in the context of COVID-19 include:

- Build on existing community and social capital to increase awareness of early years services

- Provide accessible resources to address language and literacy barriers

- Fund a ‘community connector’ or ‘peer workforce’ model

- Integrate the use of bicultural and bilingual workers in mainstream services

- Provide additional funding for interpreters

Key recommendations moving forward to ensure culturally and linguistically diverse families can access early years services are:

- Consult with people from CALD backgrounds to understand how they feel culturally safe, using an intersectional lens

- Support families experiencing vulnerability who may be facing cost or eligibility barriers to access affordable early years services

- Ensure every child can access early childhood education, regardless of where they live or the time of year

- Increase collaboration between services to promote ‘hubs’ and soft access points

- Create spaces for parents to build connections by participating in group settings

- Ensure services are run in culturally safe and familiar places such as shopping centres and libraries

- Invest in greater collaboration between outreach services to reach places where families gather

Access to timely, accurate and trusted information

VCOSS members report some culturally and linguistically diverse communities, in particular new and emerging communities, struggled to access updated and relevant information about the pandemic, particularly during the early stages of stay at home measures when information was changing regularly.

Barriers for new and emerging communities can include limited English, different stages in the establishment of structures and support systems, and difficulties understanding and navigating government systems or community agencies.

VCOSS highlighted in our substantive submission that there is a need to build on existing social capital and connection within communities. COVID-19 has highlighted that how information is disseminated, accessed, and trusted in diverse communities can differ significantly to the rest of the population. When information is changing regularly, it needs to flow through trusted and legitimate channels and through communities directly. This can be achieved through word of mouth, faith leaders, community leaders and associations, or community radio.

In some communities, particularly those who have experienced prejudice or overt racism through public discourse, or whose social and political contexts in their country of origin differs significantly to Australia, there can be a distrust of the media and governments. This makes the connection to timely, translated and accurate information from communities directly even more important during a pandemic.

While translation is important, VCOSS members report who the message reaches needed more consideration. For example, posters in communal spaces of a public housing block has limited reach when families are not able to utilise those communal spaces.

Other issues relating to the dissemination of information included assumptions of literacy, having to navigate webpages in English to reach translated information, and subsequent policing or over-policing of communities by police or neighbours when information did not flow quickly enough to children and families who were then not adhering to stay at home measures.

Strategies that would have supported culturally and linguistically diverse communities to better access the information they needed, particularly new and emerging communities, include:

- Ensure information and advice is provided through a range of media, including television, online, apps and radio and in a range of accessible formats including pictorial and oral

- For example, VCOSS members noted ad campaigns on mainstream television networks by diverse Australian celebrities, sports stars or popular culture figures would have helped to disseminate public health messages. VCOSS members report even where these messages are in English, there is significant community reach through communities seeing themselves reflected through diversity which creates talk, attention and circulation of the video amongst communities.

- Directly engage multicultural, refugee and asylum seeker organisations to support the dissemination of information

- Engage leaders of culturally and linguistically diverse communities, who are trusted sources of information, to distribute advice through their communities

- Formal and informal community networks undertook significant work in reaching their communities to provide accurate and trusted information. This role of ‘connecting’ quickly and directly, rather than waiting for information to be released in language, meant community members were doing translations on the spot. This was often the only accessible information available to people with limited or no English, literacy, or understanding of government systems (for example, to log on to the DHHS website for updated information).

- Ensure schools and universities provide information in a range of languages and formats.

Accessing services

Through stay at home measures, the shutdown of many services and closure of public and community spaces, families not already engaged in services are more likely to have faced barriers throughout the pandemic. In particular, newly arrived members of the community who have limited English and a limited understanding of the service system are at heightened risk of social isolation and missing out on key supports, due limited access to up to date and accessible information, or limited access to devices and the internet.

Local councils and community sector organisations have a range of innovative ways they bridge connection with families in ‘place’ in their local communities, who may be hard to reach in non-pandemic times. This became increasingly difficult during COVID-19. For example, families who may ordinarily be connected to services through ‘soft entry points’ such as shopping centre playgroups, or through community hubs where services are co-located have been unable to access these points of connection due to the closure of many services and no face to face contact, limiting important informal opportunities to connect.

Policing and issuing of fines for people who breached directions may have had a disproportionate impact on culturally and linguistically diverse families.

For many culturally and linguistically diverse families, stay at home measures exacerbated existing inequalities. For example, large families in overcrowded or severely overcrowded housing had limited space to study, learn or work and no access to public spaces such as libraries for relief. VCOSS members report some families in severely overcrowded housing who sought relief from going outside to the local park or open space were then approached by police, further compounding stress.

While the Victorian Government announced students would have access to onsite learning if they did not have an appropriate learning environment at home, VCOSS members report some culturally and linguistically diverse families were denied access to onsite learning, despite living in severely overcrowded housing and having access to limited or no internet or digital devices. Culturally and linguistically diverse communities were not in the government’s ‘priority cohort’ for receiving devices, sim cards or dongles. Learning from home was also a challenge for parents with limited English who could not understand how to use technology or how to support their children’s learning.

While early childhood education and care services remained open, and became free during COVID-19, adults were given limited access to these spaces to minimise the risk of COVID-19 transmission. This meant that even where families were still engaging in services onsite, parents and families were unable to gather in spaces for social connection and support. For families without access to appropriate technology, this severely restricted pathways for social connection and wellbeing support.

VCOSS members also report some new and emerging communities who did not have a detailed understanding of the service system were at a disadvantage in accessing broader supports, including telehealth or online playgroups.

The barriers presented in the shutdown of services highlights the importance of families already being engaged in a range of early years services to support connection and wellbeing throughout times of crisis. Outreach services and deeper integration of services is vitally important to ensure all families are able to deeply connect with their local communities. Existing engagement supports follow-ups and check-ins from services – but, if services don’t know who may be vulnerable and who may be missing out on support, this constrains the ability for targeted outreach and connection during a pandemic.

Engagement: an early learning sector strength

One of the key strengths of the early learning sector is its engagement and connection with families. One VCOSS member, a peak body for early learning services, reported that a number of services (predominantly kindergartens) with culturally and linguistically diverse families had positive engagement with families and children during COVID-19, including through the use of ‘remote learning’ resources.

Strong relationships and trust between services and families was fundamental to the ability of services to work positively with families in informing them about stay at home measures, accessing their services (be it on-site or through learning from home), and understanding the needs of each child and their families. Building relationships, trust and engagement also enabled services to:

- Utilise existing communication channels such as email and apps to stay connected with children and families

- Understand the needs of children and their families and use a range of strategies to sustain engagement and meet these needs, including:

- providing tailored activities to suit the learning from home environment – from providing one activity a day to a range of activities to engage a child for many hours, and drawing on items usually found in the home to support activities

- learning about other challenges families were facing such as supporting learning from home for school-aged children, managing work, including job loss, supporting extended family, and being generally exhausted.

Access to digital devices and technology did not appear to be a significant issue for these families for the purposes of remote early learning.

Many services reported having existing staff from a diversity of cultural backgrounds with a number of languages spoken, helping to build trust, cultural safety and understanding between services and families. Some services are reporting 100 per cent reengagement of culturally and linguistically diverse families back to their services.

VCOSS notes that these learnings and positive experiences are only a small sample of a large and diverse early learning sector. However, this does highlight the strength of the early learning sector in engaging families who are linked in with their services.

It also highlights the importance of integrating bicultural and bilingual workers and growing the diverse workforce to reflect the diversity in the community. This helps with the accessibility and understanding of early learning, and supports services in understanding how they can create culturally safe environments for children and families.

Asylum seekers and refugees

VCOSS understands there has been a significant increase in presentation of refugee and asylum seeker families with children to emergency relief support services during COVID-19.

Many asylum seekers and refugees experienced heightened financial vulnerability during the pandemic. Being ineligible for the Commonwealth’s JobKeeper subsidy meant many asylum seeker and refugee workers were amongst the first to be laid-off when businesses closed, and without access to appropriate government income support, many families have relied on community service organisations to meet basic needs like covering the costs of housing and purchasing food.

Increased financial vulnerability had significant flow-on affects including exacerbating the digital divide and therefore ability of families to engage in services or gain appropriate supports (for example telehealth, remote learning), which then in turn had impacts on isolation and wellbeing.

Impacts experienced by asylum seekers and refugees during COVID-19

Many of these impacts have been experienced by the broader population, including culturally and linguistically diverse members of the community who have permanent residency, Australian citizenship or other substantive visas. However, little to no access to government income support and more precarious employment means the experience of these impacts for asylum seekers and refugees are more severe.

Key challenges faced by asylum seeker and refugee families relating to accessing services and education include:

- Financial vulnerability and subsequent inability to meet basic needs or purchase devices or internet for accessing information, services and remote learning.

- Stigma in accessing or to be seen to be accessing support services, including in rural areas.

- Digital exclusion and impacts on remote learning.

- Not understanding the restrictions, and also the support and assistance they are eligible for or are able to access. For example, some families were reluctant to request devices for remote learning as they worried they would have to pay for it.

VCOSS members also reported the intersection between cultural and lived experience and technology barriers were complex. For example, as supported playgroups were not able to run in person during COVID-19, some services moved to online digital playgroups. VCOSS members report a distrust in technology and surveillance as well as defined gender roles, acted as a barrier for some families to engage in these digital playgroups. This occurred even where there was enthusiasm from the mother, due to the husband’s distrust of technology and surveillance.

These barriers demonstrate the need for culturally and linguistically diverse communities to have greater input into emergency planning and for greater resources to become available to support access and engagement in services so that families are well connected during times of crisis.