Home: the foundation for a good life Housing and Homelessness

Home: the foundation for a good life

Introduction

Housing is the foundation for a good life.

Having a place to call home that is safe, affordable, secure, healthy and fit-for-purpose, creates the conditions for people to thrive – for example, to participate and achieve in education and training, find a job and hold onto it, and engage in other health-protecting and health-promoting behaviours.

Victoria has the best performing economy in the country, but not all Victorians are sharing in the state’s prosperity. There are 25,000 Victorians who are homeless on any given night.

We are faced with this problem today because successive governments, at all levels, have largely treated the symptoms of homelessness in Victoria – for example, through programs that respond to individual-level factors or characteristics. These programmatic responses are important, but without concurrent and sustained action on the underlying structural and systemic causes of homelessness, demand-management becomes the focus, funding and practice orient to squeaky wheel crisis responses, homelessness prevention is crowded out, and the broader societal goal of ending homelessness is lost.

VCOSS wants to end homelessness.

This submission focuses on reorienting policies, funding and practice from crisis towards prevention. We will never end homelessness unless we effect this shift.

VCOSS believes that sustained action is required by all levels of government and the community focused across four priorities:

- A big build of public and community housing

- Action to end poverty, disadvantage and insecurity

- A strong services system which can prevent homelessness

- The right supports delivered at the right time

This submission draws on the vast expertise of VCOSS members, including housing and homelessness services, and other community sector organisations whose work interfaces with the specialist homelessness service system. We acknowledge that many have made their own submissions to this Inquiry, which highlight the critical work they do to support the Victorian community every day with legal, health, family and financial issues that cause or are caused by their experiences of homelessness.

This submission focuses on structural level issues, as we know that the impact of our members’ work would be maximised if there was enough housing available for their clients, and if other structural drivers of homelessness were addressed. We need a systemic reorientation to prevention.

That is what VCOSS believes will end homelessness in Victoria.

Summary of Recommendations

A big build to end homelessness

- Build 6,000 new public and community homes each year for the next decade.

- Ensure that new housing is:

- Well-located in proximity to employment opportunities, public transport connections and services

- Safe and healthy, meeting minimum standards for energy efficiency, safety and accessibility

- Stock which meets priority and under-serviced needs

- A mix of Director of Housing owned and managed public housing properties and community housing properties

- Mandate universal housing standards in all new social housing homes.

- Ensure 300 of all new social housing homes built each year are for Aboriginal Victorians.

- Require 10 per cent of new large-scale housing developments be social housing

- Boost the funding available for social housing developments, including through increased government borrowing and an expansion of existing funding pathways (such as the Social Housing Growth Fund).

- Provide access to government information on vacant land and social housing demand to inform and generate development partnership opportunities.

- Switch to a broad-based land tax.

Address the structural drivers of homelessness

- Pursue economic development strategies that prioritise employment-intensive growth and yield jobs that can be filled by disadvantaged jobseekers.

- Invest in programs that build the skills and capabilities for working-age Victorians who face barriers to sustainable employment.

- Advocate to the Commonwealth Government to increase the maximum rates of rent assistance by 30 per cent and index payment to median rent movements.

- Advocate to the Commonwealth Government to maintain increased income support post COVID-19 pandemic.

- Empower communities to design and deliver place based-responses to disadvantage.

- Provide communities with funding for “backbone support” to manage, coordinate and deliver place-based responses.

- Establish an end date for all Victorian renters to benefit from reforms under the Residential Tenancies Act and Regulations.

- Provide ongoing training and education to rental providers and renters about their updated rights and responsibilities under the Residential Tenancies Act and Regulations.

- Provide accessible information on tenancy rights to renters in different formats and languages.

- Provide quarterly wait list and allocations data from Victorian Housing Register disaggregated to provide indicators on social housing outcomes for priority populations.

- Align community housing providers’ policies with public housing policies to provide consistency for vulnerable tenants across all social housing types.

- Support the community housing sector to house tenants on very low incomes, those with complex needs, or with other vulnerabilities.

- Strengthen mechanisms for community housing tenants to contribute to good practice and development of the sector.

Ensure the community sector can prevent homelessness

- Increase default contract lengths for community services to seven years, per the Productivity Commission recommendation in “Reforms to Human Services” report.

- Pursue funding models for community service organisations that are sustainable, flexible and reduce burdensome reporting requirements.

- Provide community service organisations with a responsive funding indexation formula, that reflects the real costs of service delivery.

- Advocate to the Commonwealth Government to extend the Equal Remuneration Order supplementation or increase the base rate of grants to incorporate the current rate of supplementation.

- Expand the assertive outreach and supportive housing team model across Victoria.

- Provide opportunities for pilots and trials to be replicated and scaled, or key learnings to be applied to other programs, where evidence demonstrates their impact.

- Invest in housing as a key solution to deliver on social policy and service system reforms.

- Decriminalise the offence of begging.

- Examine and review the impact of Victoria’s current bail laws on people experiencing homelessness.

- Increase funding for the Court Integrated Services Program and other bail support programs across Victoria.

- Establish a policy, framework and guidance for first responders to engage appropriately with people experiencing homelessness and divert them out of the criminal justice system and connected disadvantage.

- Adopt a service-based, therapeutic response to issues associated with homelessness in public space.

- Increase access to diversion and therapeutic justice programs.

- Develop a framework for planning, coordinating and delivering mental health, accommodation support and social housing for people leaving hospital.

- Increase the capacity of the Judy Lazarus Transition Centre and establish an equivalent centre for women.

- Increase access to housing workers in prison.

- Establish a 12-month prison transition program, incorporating housing, health and social services, based on the ACT Extending Throughcare Pilot Program.

- Expand eligibility and funding for the Home Stretch initiative, so that every Victorian care leaver has the option to access extended care from age 18 until age 21.

- Engage services and their clients on disaster resilience, to capture the range of networks, relationships, expertise and knowledge.

- Ensure people who are homeless are included in planning, preparation and responses to emergencies.

Deliver the right support at the right time

- Support mainstream agencies with ‘first to know’ potential to identify and address risk factors for homelessness.

- Strengthen local partnerships between ‘first to know’ agencies and specialist services.

- Ensure human centred design in community service planning, funding and delivery.

- Expand the common clients framework across the whole of government to enable early intervention and coordinated support.

- Ensure every child and family can access universal parenting support.

- Fund comprehensive support services to support family preservation and reunification, including family focused therapies.

- Recognise and resource informal carers of young people experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

- Establish a statewide early intervention framework for social services to improve responses to children and young people experiencing homelessness.

- Invest in primary prevention of family violence.

- Guarantee funding for flexible support packages as a permanent service offering within the integrated response to family violence.

- Scale up models that integrate housing and responsive mental health care and support across both private and social rental tenure.

- Embed mental health support in outreach responses.

Homelessness in Victoria

A big build to end homelessness

There is a housing affordability crisis in Victoria. This is one of the most significant structural drivers of homelessness. We can only end homelessness if we have enough housing that is affordable and appropriate to people’s needs.

Across Victoria, house prices are increasing faster than incomes.[1] As a consequence, Victorians are increasingly turning to the private rental market for affordable housing. While renting used to be a transitional form of tenure on the way to home ownership, Victorians are renting for longer, resulting in very low vacancy rates, and subsequent increasing rents.

In December 2019, only 7 per cent of all new rental properties were affordable to people on low incomes.[2] Melbourne is the fifth most unaffordable major housing market in the world.[3] This market places people on low incomes at significant risk of homelessness.

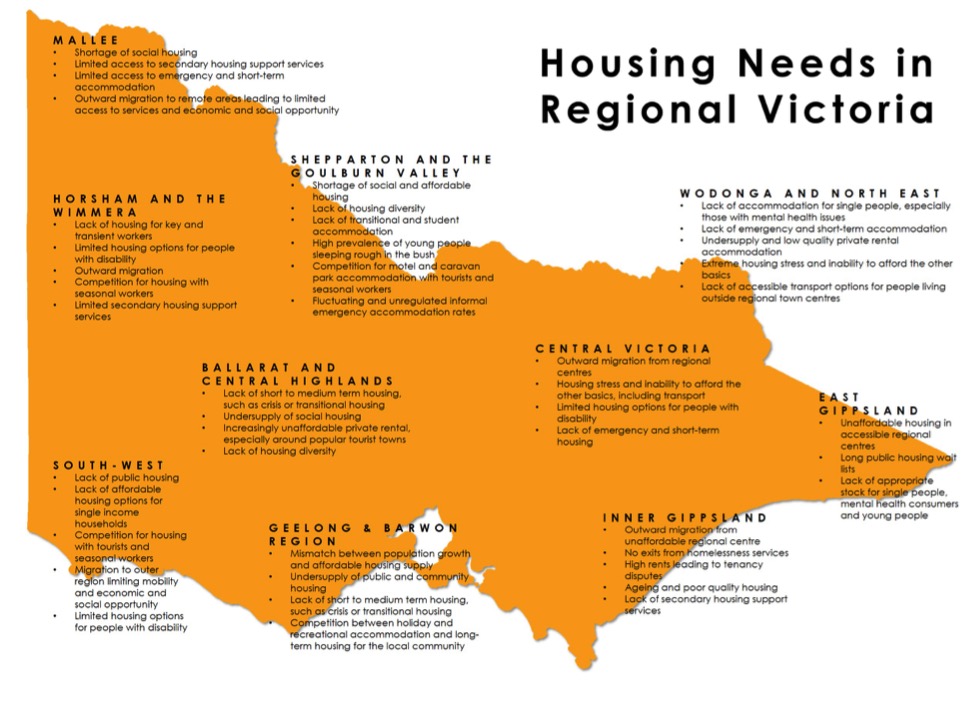

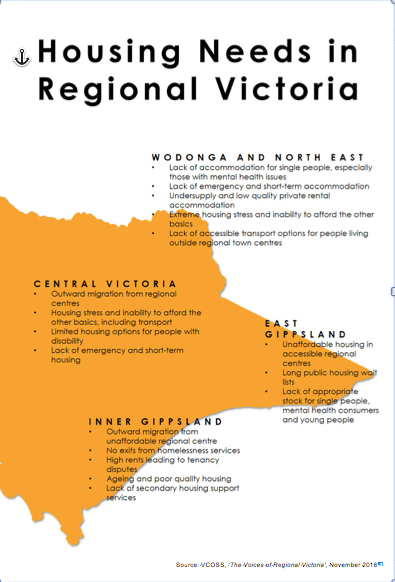

Unaffordable rent is a problem that has been worsening over time (see Figure 1). Historically, affordable housing has been more available in regional Victoria. But this is changing, and many people with low incomes cannot afford housing in regional Victoria either (see p. 8 for housing needs in regional Victoria). Tourist and seasonal workers compete for available homes, pushing people from regional centres into smaller rural communities in search of affordable housing. They can find themselves with fewer job prospects, transport options and support services.[4]

The private rental market is not delivering for vulnerable renters. For this group, affordable housing can only be guaranteed by social housing (public and community housing) and the security of tenure that social housing provides.

But the pressure on our current social housing stock is stark. More than 82,000 Victorians remain on the wait list for public and community housing[5]. It is projected to reach 100,000 by mid-2020.[6]

Social housing explained

Social housing is short-term and long-term rental housing owned and run by the government or not-for-profit agencies. It includes both public housing and community housing. It is for people on low incomes, especially those who have recently experienced homelessness or who have other special needs.

Rent for social housing is set as a proportion of income. In Victoria, public housing tenants are charged 25 per cent of their income, or the market rent, whichever is lower.

Community housing organisations usually charge tenants between 25 to 30 per cent of their income plus the value of the Commonwealth Rent Assistance that each tenant receives, or 74.99 per cent of the market rent, whichever is lower.

It is clear that the current social housing system in Victoria, both public and community housing, is unable to meet demand.

Growing public and community housing is the most significant effort required to end homelessness in Victoria. This will protect those most excluded from the private market, including people on low incomes, people with complex needs and people who experience discrimination, from homelessness. An adequate supply of social housing underpins the effectiveness of all other action highlighted in this submission.

Start construction on 6,000 new public and community homes each year for the next decade

- Build 6,000 new public and community homes each year for the next decade.

- Ensure that new housing is:

- Well-located in proximity to employment opportunities, public transport connections and services;

- Safe and healthy, meeting minimum standards for energy efficiency, safety and accessibility;

- Stock which meets priority and under-serviced needs;

- A mix of Director of Housing owned and managed public housing properties and community housing properties.

- Mandate universal housing standards in all new social housing homes.

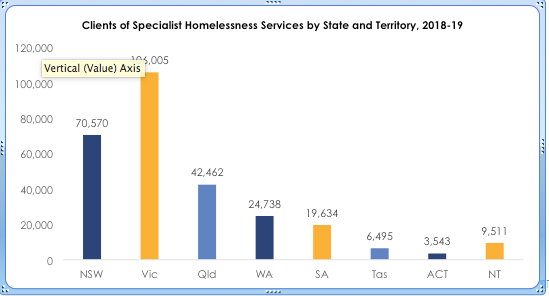

While the Victorian population, house prices and rents all increase, government investment in social housing has decreased.[7] Social housing currently makes up only 3.2 per cent of all housing in Victoria. This is well below the national average of 4.5 per cent.[8] Victoria spends the least of all Australian states and territories on social housing per person.[9] This has flow-on effects for the Victorian specialist homelessness service system, which sees the most clients annually of all the states and territories (see Figure 3).

Figure 1. Source: AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection Data 2018-19

In 2019, the Victorian Government started construction on 1,000 new social housing homes committed under the Homes for Victorians strategy. VCOSS has welcomed this much-needed investment. It is a good start. However, more is needed, given projections that there will be 100,000 Victorians waiting for homes on the Victorian Housing Register by mid-2020, and nearly 1 million Victorians already live in housing stress.[10] Of these, those on the lowest incomes live in rental properties unsuitable to their needs, live in overcrowded houses, or live in other marginal housing.

To simply maintain the current level of social housing at 3.2 per cent of all households, we would need 3,500 new public and community homes to be built each year for the next 10 years.

But to meet the demand indicated by the Victorian Housing Register, the rates of housing stress and homelessness, and match the level of social housing in other states, we need 6,000 new public and community homes to be built each year for the next 10 years.[11]

Individuals and families who need social housing in Victoria are diverse, and new social housing homes should reflect this. New homes should be well-located and the construction mix should address the current mismatch between supply and demand.

For example, there is a significant shortage of properties suitable for a single person, which may be older Victorians or individuals leaving hospital, prison or family violence situations. Presently, many individuals exit prison into emergency accommodation or rooming houses, others remain in violent situations to avoid homelessness, or cycle through the homelessness service system. At the other end of the spectrum, a lack of housing suitable for large families has resulted in increased rates of severe overcrowding.

New social housing homes should also meet the needs of an ageing population, including wellbeing, safety and access needs. The Livable Housing Design Guidelines provide aspirational targets for all new homes to be of an agreed livable housing design standard by 2020. However, it is estimated that only 5 per cent of new housing construction will meet the standards by 2020.[12] Compliance with these guidelines can deliver housing which meets the needs of people excluded in the private rental market, and can prevent homelessness and poor quality housing for older Victorians and Victorians with disability.

While there is much to be done to address the structural and systemic drivers of homelessness, and improve individual responses to homelessness, VCOSS strongly believes that building more social housing is the most effective way of preventing homelessness in Victoria.

Build homes for Aboriginal Victorians

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ensure 300 of all new social housing homes built each year are for Aboriginal Victorians.

Aboriginal[13] Victorians made up 9 per cent of all homelessness service users in 2018-19[14], despite making up only 0.7 per cent of the Victorian population. Aboriginal Victorians already disproportionately experience worse health outcomes, over-incarceration, and family violence.[15] Homelessness compounds this disadvantage.

Aboriginal homelessness is strongly associated with the experience of dispossession and dislocation.[16] As a consequence, the structural drivers of homelessness in Victoria – the critical social housing shortage, housing unaffordability and poverty – have specific adverse effects on Aboriginal Victorians. Further, mainstream social services in Victoria, including housing and homelessness services, imposes a model of support which does not meet the needs of many Aboriginal Victorians.

The newly launched Aboriginal Housing and Homelessness Framework is a critical first step to enabling an Aboriginal self-determined response to homelessness. The Government can ensure the effectiveness of this strategy by committing to building more social housing homes especially for Aboriginal Victorians.

Improve housing and land use policies to enable social housing growth

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Require 10 per cent of new large-scale housing developments be social housing.

- Boost the funding available for social housing developments, including through increased government borrowing and an expansion of existing funding pathways (such as the Social Housing Growth Fund).

- Provide access to government information on vacant land and social housing demand to inform and generate development partnership opportunities.

- Switch to a broad-based land tax.

As well as direct investment to grow social housing stock, the Victorian Government can provide a sustainable pathway out of homelessness by improving policy to facilitate social housing growth. Victoria’s current planning policy framework and system could be strengthened to address the growing gap between supply of and demand for affordable housing, including social housing.

The Victorian Government can build on action already underway, including the inclusionary zoning pilot, the use of government land for social housing, and boosting funding for social housing developments, such as the Social Housing Growth Fund. Further, the Victorian Government can explore new mechanisms to grow social housing, including increasing government borrowing.

Our current land tax policy, stamp duty is a regressive tax which encourages property speculation and dampens economic activity. As a consequence, both buyers in the market and the Victorian Treasury are subject to a volatile housing market. The system could be stabilised and made more efficient and fair by switching from stamp duty to a broad-based land tax.

Address the structural drivers of homelessness

The scale of the problem we currently face requires more than just providing supports to individuals and families experiencing homelessness. Barriers which limit people’s social and economic participation and their ability to maintain their housing and living costs can be eliminated to prevent homelessness at the structural level.

A critical structural barrier to a good life is poverty. For most people, housing is the biggest expense in their regular budget. The cost of housing is a significant contributor to poverty, and trying to maintain housing costs while living in poverty is a risk factor for homelessness. People with lower housing costs can achieve a higher standard of living than people with the same income but higher housing costs. We cannot expect to end homeless in Victoria without doing something about poverty. The VCOSS Poverty Atlas shows that 13 per cent of Victorians live in poverty.[17] Poverty exists in every Victorian community, but rates are even higher in regional and rural Victoria.

As well as preventing homelessness, addressing poverty enables a good life by giving people the means to cover their costs of living, afford essentials, take care of their health and be part of a community. To address poverty, employment and social security policy need to be reimagined and transformed. While we appreciate that these three policies are the Commonwealth’s jurisdiction, the State can play an important advocacy role, and we cannot make recommendations about ending homelessness without consideration of these issues.

People on low incomes or facing poverty and disadvantage are more likely to live in rental housing than other Victorians. Victorians experiencing disadvantage can be highly vulnerable to housing insecurity when living in rental housing, being subject to unnecessary evictions, disempowered in disputes with property owners, exposed to unnecessary costs, and vulnerable to poor housing conditions.

The recent reforms to the Residential Tenancies Act and the accompanying Regulations provide a strong foundation for making renting fair in Victoria. But there is more to be done to ensure that all Victorian renters benefit from the reforms and are protected from rental conditions which place them at risk of homelessness.

Provide support for disadvantaged jobseekers

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Pursue economic development strategies that prioritise employment-intensive growth and yield jobs that can be filled by disadvantaged jobseekers.

- Invest in programs that build the skills and capabilities for working-age Victorians who face barriers to sustainable employment.

The vast majority of people using homelessness services in Victoria are unemployed or not in the labour force,[18] which highlights unemployment as a structural risk factor for homelessness.

However, work does not automatically safeguard against homelessness. Australia has seen growth in ‘in-work poverty’. Over 11,000 people who used homelessness services in 2018-19 were in full-time or part-time employment.[19] Having insecure work or being underemployed also places individuals at risk of homelessness.

There is only one job available for every five people looking for paid work in Australia.[20] Roughly 40 per cent of all jobs in Australia are now “non-standard” (i.e. “multi-party employment relationships, dependent self-employment and various forms of non-permanent employment arrangement”).[21]

Many Victorians are now employed insecurely and there is an increasing polarisation of employment into high-skilled, high-paying jobs, and low-skilled, low-paying roles.[22] People in insecure employment generally experience less protection from termination, limited entitlements and often receive lower pay.[23]

The promotion of independent contracting through the gig economy is an example of insecure work that has flourished in recent times, alongside rising casualisation, sham contracting and labour hire.[24]

Many vulnerable people have no alternative to insecure work.[25] People who face multiple disadvantages are more likely to experience insecure work, underemployment and be at higher risk of unemployment. This includes vulnerable young people, Aboriginal people, people with disability, single parents, older people, women, people with low levels of education, people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities, migrants, people living in rural, regional, outer suburban areas, or low socioeconomic communities, and those with a history of contact with the justice system.

Stable paid employment provides people with an income and the ability to maintain housing that is affordable and appropriate to their needs. But the changing nature of work is putting more people at risk of insecure work and unemployment, and needing social security assistance as a result.

Lift people on social security from poverty

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Advocate to the Commonwealth Government to increase the maximum rates of rent assistance by 30 per cent and index payment to median rent movements.

- Advocate to the Commonwealth Government to maintain increased income support post COVID-19 pandemic.

Newstart was so low, it trapped people in poverty.[26]

As a result, if you were on Newstart, you could not achieve a basic standard of living. Basic daily essentials, including housing, but also food, bills, clothing and public transport, were unaffordable.

VCOSS members providing emergency relief and material assistance report they are inundated with requests for assistance by community members who do not have enough income to live on, let alone move themselves out of poverty.

As we previously discussed, housing costs in Victoria have increased significantly in recent years. But rent assistance has not kept up with the costs of renting in Victoria. About 60 per cent of people receiving Newstart and Commonwealth Rent Assistance were in housing stress, spending more than 30 per cent of their income in rent. About 40 per cent of young people receiving youth allowance spend more than half their income on rent.

VCOSS welcomes the increases to income support included in the COVID-19 stimulus packages. These long overdue increases will provide relief for people who have lost their incomes as a consequence of the pandemic. VCOSS believes that maintaining higher levels of income support in the aftermath of the pandemic is essential to protecting people from poverty and homelessness in the long-term.

Invest in place-based solutions to disadvantage

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Empower communities to design and deliver place based-responses to disadvantage.

- Provide communities with funding for “backbone support” to manage, coordinate and deliver place-based responses.

Poverty and disadvantage can become systemically entrenched in communities. People living in Victoria’s most disadvantaged communities have poorer wellbeing outcomes, including housing stress, inadequate housing and homelessness. Solving complex issues, like entrenched disadvantage, needs to start with empowering these communities and their members to thrive, and work towards a common aim of wellbeing and resilience.

Victoria is too diverse for a one-size-fits-all model when tackling complex social issues like homelessness.

Place-based approaches aim to empower people to develop local solutions and build stronger, more cohesive, connected and resilient communities. Communities know what they need and how to define themselves. More and more communities are using place-based, collaborative approaches to share responsibility for making change happen and accountability of outcomes. Some current examples include (but are not limited to) Go Goldfields in Central Goldfields Shire, GROW-21 in Geelong, and Hands Up Mallee in the Northern Mallee.

Communities have their own unique profiles, strengths and challenges. What works in one place will not necessarily work in others. To be successful, place-based responses need to be flexible and adaptable enough to suit local circumstances. This includes security and flexibility in funding that allows organisations to respond to local needs, and change and adapt. Strict contractual requirements and government bureaucracy stifle progress.

Governments can support place-based homelessness prevention responses by providing local communities with “backbone funding” for management, coordination, governance, partnership development and access to linked datasets, as well as to develop and deliver programs.

Make renting fair in all housing

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Establish an end date for all Victorian renters to benefit from reforms under the Residential Tenancies Act and Regulations.

- Provide ongoing training and education to rental providers and renters about their updated rights and responsibilities under the Residential Tenancies Act and Regulations.

- Provide accessible information on tenancy rights to renters in different formats and languages.

- Provide quarterly wait list and allocations data from Victorian Housing Register disaggregated to provide indicators on social housing outcomes for priority populations.

- Align community housing providers’ policies and public housing policies to provide consistency for vulnerable tenants across all social housing types.

- Support the community housing sector to house tenants on very low incomes, those with complex needs, or with other vulnerabilities.

- Strengthen mechanisms for community housing tenants to contribute to good practice and development of the sector.

The declining availability of social housing has seen the number of low-income households in the private rental market increase over the past two decades. Within this cohort, there are renters who are highly vulnerable to homelessness because of their significant social and economic disadvantage.[27] In such a tight market, this group faces substantial barriers to getting and keeping private rental housing. Those who can access private rental are often in the worst quality housing, subject to significant rental stress, or isolated from their networks and opportunities.

Victorian renters welcomed historic changes to rental laws in 2018. These legislative changes better reflect the reality of housing in Victoria, where more people are living in rental properties for longer. They also reflect the Victorian community’s expectation – and the State Government’s commitment – that rental housing will be affordable, safe and secure, and be responsive to the community’s needs (for example, in relation to disability, ageing, and family violence risk).

Strong laws need to be backed up by robust regulations, which the Government is currently in the process of finalising. An ongoing concern is that many of the important changes arising from this reform will not apply to all renters, including:

- Public and community housing tenants, who typically remain in their homes for many years;

- Other long term renters, such as those already on periodic agreements.

Currently, there is no “end date” for the reforms to apply to all Victorian renters. This creates a practical problem for renters and rent providers, whereby two systems with different rights and obligations operate side by side. More importantly, this gives rise to equity issues, where some renters will benefit from the reforms and others will be effectively excluded. These transitional issues should be addressed so that all Victorian renters can benefit from better conditions and protections in rental housing.

Social housing is designed to provide housing for people failed by the private market. Social housing can provide affordable housing for people on the lowest incomes or who have specific needs that the private rental market excludes.

Presently, public housing offers the most affordable rents, security of tenure and policy and procedural settings that aim to avoid evictions into homelessness, for tenants who would be at risk of eviction in other tenure types.[28]

Community housing providers should be resourced to deliver the sustained, high quality tenancy support to people experiencing vulnerability that community housing has been established to provide. Presently, the security of community housing tenure is not the same as public housing, because providers are more dependent on revenue, and are not well placed to absorb lost income from rent in arrears.

A strong community housing regulatory framework can ensure the sustainability and growth of the sector and provide appropriate oversight of the sector to government and private investors. Most importantly, it can support community housing services to be configured around the needs of people experiencing vulnerability, and help them maintain their tenancies in complex circumstances.

Ensure the community sector can prevent homelessness

All mainstream and specialist services providing social assistance have a role to play across the continuum of homelessness prevention, early intervention, response and recovery. Specialist homelessness services (SHS) are a critical part of this system, and in many cases, are the last safety net for individuals and families. SHS support people who are at risk of or experiencing homelessness to access housing, overcome the barriers to keeping a home, and foster connections to the physical, personal and community resources which create a sense of belonging and provide protective factors.[29]

The data tells us that 105 people are turned away from Victorian SHS every day because the system cannot meet their need at that time.[30] This is almost certainly an undercount. After hearing this figure at our workshop to develop this submission, a VCOSS member told us it is likely they turn away that many people from their service alone.

Social services are well-connected with some of the most vulnerable members of our community. They maintain strong relationships with people who access them and are well-placed to identify and act on the early signs of homelessness risk before a person reaches crisis point. They can also act as entry points to SHS and provide support when SHS cannot.

But disjointed policy and funding, as well as significant, but uncoordinated sector reforms have led to a fragmented and poorly coordinated service system, where services do not join up cohesively. Existing coordination mechanisms endeavor to address this, but issues persist. The sector is characterised by funding uncertainty and beset by stop-start activity: agencies continue to receive funding for limited services, programs or trials.

People navigating this system often face far too many wrong doors before they get the support they need. To end homelessness, we need to address the institutional and systemic failures that place people at risk of homelessness or create barriers to people accessing the support they need to exit homelessness.

Make quality services certain

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Increase default contract lengths for community services to seven years, per the Productivity Commission recommendation in “Reforms to Human Services” report.

- Pursue funding models for community service organisations that are sustainable, flexible and reduce burdensome reporting requirements.

- Provide community service organisations with a responsive funding indexation formula, that reflects the real costs of service delivery.

Managing short-term funding allocations, time-limited project grants and last-minute funding extensions is one of the biggest challenges facing the community services sector.

Funding certainty is an essential condition for social services to plan for future demand, develop best practice service delivery and be resilient to shocks, and – crucially – to provide effective support to individuals and families at risk of or experiencing homelessness.

Funding uncertainty limits the ability of organisations to deliver quality services and retain skilled staff. This means turnover and instability for workers and disrupts relationships workers have with their clients and community partners.

Funding bodies use a standard service agreement lasting four years, supplemented by many short-term contracts. These short-term arrangements often roll over repeatedly. This increases uncertainty for community service organisations and their staff, who must constantly reapply for funding, diverting time and energy from the work of delivering services.

No organisation can operate to its full potential with a series of funding cliffs always looming on the horizon.

The Productivity Commission recommends community service contracts be extended to seven years.[31] The Victorian Government should adopt this as the new standard for community sector funding.

Value the social services workforce

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Advocate to the Commonwealth Government to extend the Equal Remuneration Order supplementation or increase the base rate of grants to incorporate the current rate of supplementation.

Community service organisations benefited from the landmark Fair Work Commission decision in 2012, the Equal Remuneration Order (ERO) that addressed the gendered under-evaluation of work performed in much of the community services sector.

As a result, wages increased by up to 45 per cent over 10 years, and most governments across Australia, including the Federal Government, provided additional funding to ensure that community sector organisations could pay fair wages and maintain essential services to our communities. The funding for this additional supplementation is secured by legislation that expires next year.

The sector is deeply concerned about the impacts on the industry and the community if the Federal Government ceases paying ERO supplementation from July 2021. This will affect homelessness, families and children, domestic violence and other community services.

If the base grant for programs currently receiving ERO supplementation does not rise to incorporate the ERO payments, it will result in significant funding cuts for community sector organisations delivering federally funded programs. This will mean cuts to the services that people in communities across Australia rely on. It also means that the gains in gender equity achieved as a result of the Equal Remuneration Order will be diminished by job cuts in the community sector’s predominantly female workforce.

Community service organisations simply cannot absorb cuts of this magnitude. It will inevitably mean reductions in services to vulnerable people in the community and job losses for workers in the industry. VCOSS member organisations are already beginning to consider their options, including laying off staff, reducing hours and closing offices.

Ensure equitable access to supports that people need

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Expand the assertive outreach and supportive housing team model across Victoria.

- Provide opportunities for pilots and trials to be replicated and scaled, or key learnings to be applied to other programs, where evidence demonstrates their impact.

There have been some opportunities for SHS and community housing providers to trial the effectiveness of new models identified as contemporary best practice, arising from funding under the Royal Commission into Family Violence in 2016, the National Partnership on Homelessness in 2017 and Homes for Victorians in 2018.

However, as a consequence of trial, short-term or geographically limited funding, the support a person might get depends on where they turn. People who are lucky enough to access a best practice trial have seen good results. For others, including the 105 people who are turned away from homelessness services on a daily basis,[32] the outcomes are not as good.

For example, in 2017, eight assertive outreach and six supportive housing teams were established to respond to the increased prevalence of rough sleeping in hotspot locations. While this is a good start, this model should be delivered across Victoria.

Further, the Royal Commission into Family Violence gave rise to innovative interventions to respond to family violence related homelessness, such as the Family Violence Housing Blitz. While this has delivered significant outcomes to victim-survivors who have accessed program, without ongoing investment in such programs across the state, family violence related homelessness remains a critical problem to be addressed.

Deliver on critical sector reforms with housing

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Invest in housing as a key solution to deliver on social policy and service system reforms.

VCOSS works across a broad continuum of social policy issues. It is our experience that housing is at the heart of almost every social policy challenge. At a time of policy and service system disruption, as all levels of government work hard to address “wicked problems”, it is vital that we do not lose sight of unfinished business. Housing – a persistent social policy challenge for the past two decades – must be a central consideration in all social policy reforms. Housing is not a peripheral issue – rather, it is a key solution.

Victoria has led the world with its Royal Commission into Family Violence. Despite many gains in responses to family violence arising from this critical sector reform, family violence continues to be the main reason people seek assistance from specialist homelessness services.

The shortage of affordable housing in Victoria is preventing victim-survivors of family violence from accessing safe and sustainable housing, and perpetrators from leaving the family home. The Royal Commission into Family Violence highlighted the complex link between victim-survivor’s safety, the ability to recover from family violence and access to long-term housing.[33]

The continued implementation of the NDIS also highlights the relationship between sector reform and housing. Only 6 per cent of NDIS participants will require specialist disability accommodation. Consequently, most NDIS participants will continue to access housing in the private market, as will people with disability who are not NDIS participants. Increasing the supply of accessible social housing and aligning the NDIS with intersecting Commonwealth and State policy will ensure that the NDIS delivers on the promise for people with disability to live independent, empowered lives in homes which meet their needs and preferences.

The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System currently underway will provide the same opportunity for system-wide improvement, but will experience the same barriers to success if it does not adequately examine housing and homelessness. Housing is a precondition for successful mental health care. Without stable and secure housing, it is very difficult for people to have their other needs met.

The key to successfully sustaining the reforms will be long-term investment in housing.

Break the link between homelessness and justice involvement

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Decriminalise the offence of begging.

- Examine and review the impact of Victoria’s current bail laws on people experiencing homelessness.

- Increase funding for the Court Integrated Services Program and other bail support programs across Victoria.

- Establish a policy, framework and guidance for first responders to engage appropriately with people experiencing homelessness and divert them out of the criminal justice system and connected disadvantage.

- Adopt a service-based, therapeutic response to issues associated with homelessness in public space.

- Increase access to diversion and therapeutic justice programs.

People who are homeless often live their daily lives in public space, since they do not have the privilege of privacy.

As a result of this, they are disproportionately exposed to punitive, enforcement based responses to their circumstances. This includes fines and charges for public space offences, such as begging, camping and conduct in public spaces, including on public transport.

A person experiencing homelessness may not be able to pay a fine because they cannot afford to or because they cannot access the necessary systems, such as the fines website. They may not be able to defend a charge without access to timely legal support.

Homelessness is a social issue, not a criminal issue. Responses to homelessness should reflect this.

It is an unnecessary burden on the justice system to subject people to fines they cannot afford to pay, and charges that a person who is housed would likely never be subject to. Reform to Victoria’s summary offence laws, including the offence of begging, could prevent people experiencing homelessness from this unnecessary and ineffective contact with the justice system. Further, first responders, such as Victoria Police, need additional training and support to respond to situations involving homelessness in public space in a non-adversarial, therapeutic way.

In 2017–18, nearly 30 per cent of people in Victoria’s prisons were on sentences of less than 12 months. Imprisonment affects people’s ability to maintain their housing. Preventing people from imprisonment enables them to sustain their housing, continue engagement with health and social services, and stay connected to their natural supports in their communities. Earlier intervention to divert people from the justice system is required. This includes ensuring access to integrated legal, social and health services to support people to address their legal issues. Further, access to diversion and therapeutic justice should be increased.

Contact with the justice system has the potential to be a positive intervention in a person’s life, if an effective, problem-solving approach is taken. The Drug Court and the Court Integrated Services Program are both good examples of this. Such models should be expanded across Victoria, including to regional Victoria. Non-adversarial justice responses such as these connect users to the health and social supports they may not have been able to access otherwise.

The recent changes to Victoria’s bail laws is contributing to the ever-increasing remand population in Victoria’s prisons. VCOSS members report that their clients may be remanded, even for minor offences, simply for not having a home to be bailed to. The Bail Act should be examines and reviewed to address this unintended consequence. Further, the Victorian Government should invest in the provision of bail accommodation and supports so that custody is the last option for people who have not been sentenced.

Guarantee no exits into homelessness

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Develop a framework for planning, coordinating and delivering mental health, accommodation support and social housing for people leaving hospital.

- Increase the capacity of the Judy Lazarus Transition Centre and establish an equivalent centre for women.

- Increase access to housing workers in prison.

- Establish a 12-month prison transition program, incorporating housing, health and social services, based on the ACT Extending Throughcare Pilot Program.

- Expand eligibility and funding for the Home Stretch initiative, so that every Victorian care leaver has the option to access extended care from age 18 until age 21.

Currently, state institutions, including hospitals, prisons and out-of-home-care, are failing to protect vulnerable people leaving their care from exiting into homelessness. 5,000 people presented to homelessness services in 2018 – 19 at risk of homelessness after leaving a state institution.[34]

Hospital

The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System has rightly identified the pressure on the number and availability of psychiatric units and beds. VCOSS members report that this results in the practice of people being discharged before they have recovered, into homelessness. Some 500 people each year are discharged from acute mental health care into rooming houses, motels, rough sleeping or other forms of homelessness.[35]

Housing that is affordable, safe, secure and stable is “protective of health, including mental health”.[36] It is also a key enabler for mental health recovery. The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System will deliver significant reform to improve access to services, improve service navigation and models of care.

For the eventual reforms to be effective, there will need to be investment in discharge planning, post-release support and follow-up and appropriate housing and support models, comprising of:

- Permanent supportive housing teams providing flexible, multidisciplinary and ongoing support;

- Housing first responses to people with complex needs;

- Specialist mental health support focused on intensive recovery.

Some states and territories have developed coordinated approaches to addressing mental health and homelessness. For example, NSW has a Housing and Mental Health Agreement and related action plan, providing an overarching framework for planning, coordinating and delivering mental health, accommodation support and social housing for people with mental illness who are living in social housing, homeless or at risk of homelessness.

Prison

Similarly, nearly half of all people leaving prison expect to be homeless, or exited to emergency accommodation. Over the past five years, the number of Victorians who have exited from prison into homelessness has grown by 188 per cent.[37]

There is no question that people are affected by any length of time in prison. Successfully returning to the community after prison begins with supporting people to prepare for transition well before they leave. This provides stability and enables strong, trusting relationships to be built that act as a protective factor against reoffending.

A person leaving prison may need financial, legal, welfare, employment and housing assistance to support their transition. They may also be engaged with a health program in prison. Post-release, they may have to arrange their own entry into equivalent services in the community – but the supports a person can access are highly variable because of a lack of coordination, information sharing and referrals between custodial and community supports and resource constraints.

To prevent people from becoming homeless when they leave prison, these interconnected cost, coordination and access problems must be addressed, in order to deliver the wraparound, stepped care that is effective for people leaving prison and returning to the community.

Comprehensive support is already offered in other jurisdictions and there are policy models that could be adopted here in Victoria. For example, the ACT Government supports people for 12 months after they leave prison, including helping them find a place to live, access mental health counselling and undergo alcohol and drug treatment, if required. The program has reduced recidivism, with participants reporting increased self-esteem, improved confidence, a greater quality of life and an enhanced ability to achieve goals. The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System also presents an opportunity to drive greater system coordination for people with justice system involvement and multiple and complex support needs.

Out-of-home care

While preventing children and families from entering out-of-home care should be the primary goal of the system, every effort is also needed to secure brighter futures for vulnerable children and young people who cannot live at home. Children and young people in out-of-home care are one of the community’s most vulnerable social groups.[38]

Young people living in out-of-home-care have often experienced significant trauma and disruption in their live. Formal care ends at 18 in Victoria, and most young people leaving care at 18 then transition to living independently. Many young people leaving care have no family or financial assistance. As a result, the transition to independence following care is often into homelessness.

Young people leaving out-of-home care are at risk of homelessness due to the lack of access to public and community housing, discrimination on the basis of age or lack of rental references; and the unaffordability of the private rental market.[39]

Where young people have reliable social connections, access to employment education and training opportunities, and financial support and assistance to access and maintain stable housing, they have a better chance at becoming independent adults, and are protected from crises.

Support the sector in the face of climate change and emergencies

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Engage services and their clients on disaster resilience to capture the range of networks, relationships, expertise and knowledge.

- Ensure people who are homeless are included in planning, preparation and responses to emergencies.

Having insecure housing or no home at all makes you more physically vulnerable to extreme weather and disasters. Further, people without a secure home can be invisible in emergency planning, preparation and responses.[40]

People who do not fully recover from a disaster are at increased risk of homelessness. This is because much of the response and support following an emergency event is provided on a short-term basis. Organisations report that without long term support, people who are displaced by disasters are at risk of longer term homelessness.[41]

The 2019-20 bushfires and the escalating COVID-19 pandemic highlight that organisations need support to prepare for emergencies, including business continuity, and strategies to assist people experiencing homelessness, to meet surges in demand. The bushfires led to surges in demand for accommodation and support in East Gippsland, a region where social housing stock is already at capacity, and social services do not have the resources to manage demand. The public health strategies underway to contain COVID-19, particularly self-isolating in your own home, are not effective for people without a home or living in marginal housing. Further, many people experiencing homelessness also have underlying health conditions and may not have ready access to health services, which places them at significant risk of the worst effects of the virus.

Deliver the right support at the right time

In 2018-19, 91 per cent of people who presented to a homelessness service were assisted to remain in their housing.[42] Conversely, only 19 per cent who presented to a homelessness service already homeless were assisted into housing.[43]

The difference in these outcomes makes two things clear: it is extremely difficult to access housing once you are homeless, and the right supports at the right time can mean the difference between becoming homeless or not.

The nature of policy and funding and a chronic lack of affordable housing has forced the sector into providing crisis driven responses to homelessness. Our members tell us that they are increasingly triaging their clients according to the level of risk. This means that where they have two presenting clients and one is homeless and one is housed, they prioritise the client who is homeless, despite knowing that assisting the housed client to stay housed would prevent them from becoming homeless.

The right time to deliver support is before an individual or family are in the midst of homelessness crisis. Instead, best practice support prioritises:

- Early intervention approaches to support individuals and families at imminent risk of homelessness or who have recently become homeless;

- Eviction prevention approaches to keep people at risk of eviction in their home;

- Ongoing flexible support for people who have experienced homelessness to exit quickly and never experience it again.[44]

Across the social services sector, there are programs delivering best practice support for people to hang onto their housing. While there is no single program that alone will end homelessness, the right supports delivered at the right time can prevent individuals and families from becoming homeless.

Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, ‘Typology of Homelessness Prevention’, 2018

Mobilise ‘first to know’ agencies

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Support mainstream agencies with ‘first to know’ potential to identify and address risk factors for homelessness.

- Strengthen local partnerships between ‘first to know’ agencies and specialist services.

‘First to know’ services and agencies are positioned to play a greater role in preventing homelessness.

Most people also come into contact with mainstream services – like hospitals, GPs, schools, or maternal child health services – at various points in their life. Such services are universally accessible, non-stigmatising and provide a diversity of support options. They can be the ‘canary in the coalmine’ – they have line of sight to emerging risk factors for homelessness. Some examples are:

- Financial counsellors or emergency relief providers can identify a family at risk of rental stress;

- School and youth services can be the first point of contact for young people having trouble living in the family home;

- Community health agencies support their clients with the many personal factors that may make maintaining a home difficult, such as chronic disease, drug and alcohol use, and mental illness.

When risk factors are identified, these services provide a “soft entry” pathway to more specialised services as needed.

To effect a systemic re-orientation to prevention, government and community will need to identify those services that do not currently have a well understood role in this space. Further, these services may not realise their own potential for contributing to preventing homelessness and would require support to capitalize on their ‘first to know’ potential.

Mobilising ‘first to know’ agencies would require substantial cooperation, collaboration and networking between different service providers at the local and regional levels so that a broad range of risks and issues can be responded to.

For example, the Melbourne City Mission (MCM) Detour Innovation Action Project involved the local Centrelink office and social work staff working in partnership with MCM, local government, local schools and Kids Under Cover. MCM staff were co-located at Centrelink, so that Centrelink staff could warm refer young people applying for UTLAH allowance, which was often a precursor to early home leaving and homelessness for young people.

Deliver supports that meet people’s holistic needs

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ensure human centred design in community service planning, funding and delivery.

- Expand the common clients framework across the whole of government to enable early intervention and coordinated support.

The most vulnerable users of homelessness and social services in Victoria may be experiencing multiple issues, such as financial difficulties, mental ill-health or family violence, alongside a housing issue. Service integration means that they can more easily access the full range of support they require,[45] and can access support they may not have been aware of or engaged with otherwise.

While we recognise that services are provided by different agencies, systems, and levels of government, a person using services should not experience them as different systems. Human centred design of social services can ensure this, by including users in planning and implementation.[46]

For example, programs that integrate housing and mental health support save money and reduce hospital admissions and length of stay. They also contribute to tenancy stability, improve people’s wellbeing, social connectedness and lead to modest improvements in involvement in education and work.[47]

Similarly, programs that integrate legal advice with other support, such as financial counselling and social work, can prevent homelessness by addressing legal and non-legal issues at the same time, and support people to hang onto their housing in the face of evictions.

The multidisciplinary teams established under the Victorian Homelessness and Rough Sleeper Action Plan have been effective in integrating housing and support for people with complex needs. Expanding this model across Victoria, and investing in similar models for other cohorts will ensure that people’s holistic needs are at the centre of service delivery.

Give children and young people the best chance

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ensure every child and family can access universal parenting support.

- Fund comprehensive support services to support family preservation and reunification, including family focused therapies.

- Recognise and resource informal carers of young people experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

- Establish a statewide early intervention framework for social services to improve service responses to children and young people experiencing homelessness.

A safe home is essential to children and young people’s wellbeing. Children and young people who experience homelessness are at risk of disengaging from education, experiencing poor health and wellbeing and developmental and behavioral issues. Further, children who experience homelessness are at significant risk of being homeless in adolescence and adulthood.[48]

10,000 young Victorians are homeless on any given night.[49] They may be in temporary crisis accommodation, alone or with their family, couch surfing or increasingly, living in severely overcrowded housing.

Family conflict, including breakdown or violence, poverty, and experiences of child protection and out-of-home care are key drivers of child and youth homelessness. Preventing this involves delivering the right supports to families early to prevent families from breaking down and family members leaving the family home into homelessness.

Nearly 15,000 young people presented to specialist homelessness services for assistance.[50] Young people experience significant barriers to getting the support they need when they are at risk of or experiencing homelessness, since young people require different approaches to supports than adults. Through programs such as Reconnect, specialist homelessness services have demonstrated their capacity to achieve good, sustainable outcomes for young people who are at risk of homelessness or in the early stages of homelessness. However, early intervention opportunities often exist before engagement with homelessness services.

To improve responses to young people accessing mainstream social services, and statewide early intervention framework for young people experiencing homelessness should be established.

As a consequence, young people experiencing homelessness may choose not to get support from this system and may instead choose to access informal support. This might involve seeking advice and information through their existing networks and relationships, rather than from services, or choosing to couch surf for emergency or temporary accommodation, instead of through housing providers.[51] These informal supports should be better recognised and resourced to ensure an effective response to young homelessness.

Keep women and children safe and housed

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Invest in primary prevention of family violence.

- Guarantee funding for flexible support packages as a permanent service offering within the integrated response to family violence.

Victoria’s Royal Commission into Family Violence recognised that women and children deserve dignity, safety and respect, and demonstrated a community-wide commitment to eliminating family violence.

The Royal Commission found that the best outcome for many victim-survivors of family violence, and an effective measure to prevent homelessness, is to be supported to stay at home. Safe at home responses need further investment in housing for perpetrators to leave the family home, and sustained funding for flexible support packages.

For victim-survivors who cannot benefit from safe at home responses, such as those who would not be able to afford the cost of their housing on a single income, increasing the supply of public and community housing and ensuring access to affordable and safe housing is essential to ending homelessness amongst victim-survivors of family violence.

Invest in housing and support to enable mental wellbeing

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Scale up models that integrate housing and responsive mental health care and support across both private and social rental tenure.

- Embed mental health support in outreach responses.

A home is the foundation for a healthy life, including mental wellbeing. It plays a key role across the continuum of mental illness prevention, early intervention, response and recovery.

People with mental illness often live in unstable housing situations, characterised by frequent moves, insecure housing and inadequate accommodation. Private and public rental housing is very difficult for people with mental illness to access, because of cost, availability, discrimination and stigma.

Homelessness causes mental ill-health. About one-third of people who seek help from homelessness services report a diagnosed mental illness.

Being homeless limits people’s ability to access mental health services. People may be unable to make and keep appointments or answer phone calls. Clinical ‘catchment areas’ are assigned based on a person’s home address. If someone is homeless, they may not be assigned to any area.

Programs that integrate housing and mental health support save money and reduce hospital admissions and length of stay. They also contribute to tenancy stability, improve people’s wellbeing, social connectedness and lead to modest improvements in involvement in education and work.[52]

Some states and territories have developed coordinated approaches to addressing mental health and homelessness. For example, NSW has a Housing and Mental Health Agreement and related action plan, providing an overarching framework for planning, coordinating and delivering mental health, accommodation support and social housing for people with mental illness who are living in social housing, homeless or at risk of homelessness.

[1] Ibid, p15.

[2] Department of Health and Human Services, ‘Rental Report – December Quarter 2019’, March 2020.

[3] Victorian Parliamentary Library and Information Service, ‘The Cost of Living: An Explainer’, April 2018, p15.

[4] VCOSS, ‘The Voices of Regional Victoria: VCOSS Regional Roundtables Report’, November 2018, p3.

[5] Parliament of Victoria, Inquiry into the Public Housing Renewal Program (Final Report), June 2018.

[6] Based on analysis by the Victorian Public Tenants Association, ‘Budget Submission 2020-21’, November 2019.

[7] Productivity Commission, ‘Vulnerable Private Renters: Evidence and Options’, September 2019, p2.

[8] Department of Health and Human Services, ‘Housing Assistance: Additional Service Delivery Data 2018 – 19’, September 2019.

[9] Productivity Commission, ‘Report on Government Services 2020 – Part G, Section 18’, January 2020.

[10] The ABS estimates that 962,500 Victorians live in households paying more than 30% of their income towards housing costs. See Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4130.0 – Housing Occupancy and Costs, 2015-16, Table 13.5 Household Estimates, Selected household characteristics, States and Territories, 2015-16.

[11] Derived from DELWP, Victorians in Future 2019 (VIF2019), July 2019, p8 and DHHS, Housing Assistance: Additional Service Delivery Data 2018 – 19, September 2019, p8.

[12] Disabled People’s Organisations Australia, ‘Status of Women and Girls with Disability in Australia’, 2019.

[13] The term ‘Aboriginal’ is used in this submission to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

[14] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Specialist Homelessness Services Annual Report 2017–18: Indigenous Clients’, 2018.

[15] State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services, ‘Korin Korin Balit-Djak; Aboriginal Health, Wellbeing and Safety Strategic Plan 2017–2027’, 2017.

[16] Aboriginal Housing Victoria, ‘The Victorian Aboriginal Housing and Homelessness Framework’, February 2020.

[17] VCOSS, ‘Every suburb, every town: mapping poverty in Victoria’, November 2018.

[18] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Specialist Homelessness Services Data Tables 2018-19’, December 2019.

[19] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Specialist Homelessness Services Data Tables 2018-19’, December 2019.

[20] Joshua Healy & Daniel Nicholson, ‘The costs of a casual job are now outweighing any pay benefits’ in The Conversation, September 2017

[21] Australian Council of Trade Unions, ‘Australia’s insecure work crisis: changing it for the future’, 2018

[22] OECD, ‘OECD Employment Outlook 2017’, June 2017, p.85.

[23] International Labour Organization, ‘Digital labour platforms and the future of work: Towards decent work in the online world’, October 2018, p.xviii.

[24] Frances Flanagan, ‘Theorising the gig economy and home-based service work’, Journal of Industry Relations, November 2018, p2.

[25] OECD, ‘OECD Employment Outlook 2014’, June 2014, p.151.

[26] ACOSS and UNSW Sydney, ‘Poverty in Australia 2020’, March 2020.

[27] Productivity Commission, ‘Vulnerable Private Renters: Evidence and Options’, September 2019, p4

[28] Guy Johnson, Rosanna Scutella, Yi-Ping Tseng & Gavin Wood, ‘How do housing and labour markets affect individual homelessness’, November 2018.

[29] Council to Homeless Persons, ‘Position Paper on the Victorian Homelessness Action Plan Reform Project: A Framework for Ending Homelessness’, 2013.

[30] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Specialist Homelessness Services 2018-19: Victoria’, September 2019.

[31] Productivity Commission, ‘Introducing Competition and Informed User Choice into Human Services: Reforms to Human Services’, October 2017.

[32] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Specialist Homelessness Services 2018-19: Victoria’, September 2019.

[33] Royal Commission into Family Violence, ‘Report and Recommendations: Volume II’, March 2016, p38.

[34] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Specialist Homelessness Services Annual Report 2018-19’, September 2019.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Debra Rickwood, ‘Pathways of Recovery: Preventing Further Episodes of Mental Illness (Monograph)’. November 2005.

[37] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘The Health of Australia’s Prisoners 2018’, May 2019.

[38] Andrew Harvey, Patricia McNamara, Lisa Andrewartha, Michael Luckman, ‘Out of care, into university: Raising higher education access and achievement of care leavers’, La Trobe University, May 2015.

[39] AHURI, ‘The Risk of Homelessness for Young People Exiting Foster Care,’ June 2018.

[40] VCOSS, ‘Easing the Crisis: Reducing Risks for People Experiencing Homelessness in Disasters and Emergency Events’, May 2016, p7.

[41] Ibid, p7.

[42] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Specialist Homelessness Services Annual Report 2018-19’, September 2019.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, ‘Typology of Homelessness Prevention’, 2018.

[45] QCOSS, ‘Housing and Homelessness Service Integration Literature Review’, March 2016.

[46] Ash Centre for Democratic Governance and Innovation, ‘Design Thinking for Better Government Services’, July 2018.

[47] AHURI, ‘Housing, Homelessness and Mental Health: Towards System Change’, November 2018, p1.

[48] Paul Flatau, Elizabeth Conroy, Catherine Spooner, Robyn Edwards, Tony Eardley and Catherine Forbes, ‘Lifetime and intergenerational experiences of homelessness in Australia,’ AHURI Final Report No. 200, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne, February 2013.

[49] Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness 2016 – State and Territory of Usual Residence, All Persons’, July 2018

[50] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Specialist Homelessness Services Annual Report 2018-19, September 2019.

[51] Shorna Moore, ‘Couch Surfing Limbo: Legal, Policy and Service Gaps Affecting Young Couch Surfers and Couch Providers in Melbourne’s West’, WEstjustice, August 2017.

[52] AHURI, ‘Housing, Homelessness and Mental Health: Towards System Change’, November 2018, p1.