Diverse female workers meeting outside

Submission to the inquiry into the Skills for Victoria’s Growing Economy Community Sector

Submission to the inquiry into the Skills for Victoria’s Growing Economy

Introduction

The Victorian Council of Social Service (VCOSS) is the peak body for social and community services in Victoria. VCOSS supports the community services industry, represents the interests of Victorians facing disadvantage and vulnerability in policy debates, and advocates to develop a sustainable, fair and equitable society.

VCOSS welcomes the opportunity to provide input into the Victorian Government’s Skills for Victoria’s Growing Economy Review.

A high-quality post-secondary education and training system is a corner stone for social and economic inclusion.

Within this system, TAFEs and not-for-profit community-based vocational education providers with a strong focus on access and equity play a particular role in “support[ing] sustainable, socially just and inclusive societies”, as well as producing workers with the right skills and knowledge for the economy[1].

The world of work is rapidly changing. This Review is an opportunity to identify refinements to the VET system, so that it can optimally support social and economic reforms and changing skill and job demand.

Victorians need sets of transferrable ‘complex skills’ such as adaptability, creativity and problem solving to be able to move between jobs and careers as automation and areas of job growth change. The era of being a ‘lifelong’ employee linked to one employer is a thing of the past – research suggests young people today are likely to have 17 jobs over five careers in their lifetime[2].

For many Victorians, these jobs will be in the community services industry – one of the State’s fastest growing industries. The drivers for this growth are increasing demand for social assistance (including new and emerging forms of community need) and structural reform (current and pending industry transformation and growth associated with Royal Commissions into family violence, mental health, disability and aged care, as well as the introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme). Currently, workforce shortages are a significant issue – sub-sectors such as family violence, disability, aged care and early childhood education are often competing for the same talent. Victoria’s post-secondary education system needs to be adaptive and responsive to ensure we have the right workforce to deliver the promise of these reforms, and so that Victorians have the skills required to take advantage of these opportunities.

More broadly, for Victoria to have a world-class VET system, it will need to be nimble and flexible – able to accommodate significant shifts to align with the needs of priority industries (community services, and beyond) and the diverse needs of students.

This submission identifies key areas of change that will support a high-quality and agile VET system, including:

- Improvements to data capturing to enable timely and robust decision-making

- Less restrictive and more equitable funding structures to support innovation

- Greater access to subsidised courses to promote lifelong learning

- Wrap-around supports for students experiencing disadvantage

- A move towards capabilities and ‘complex skills’ over competency-based training

- Improved opportunities for on-the-job training.

Recommendations

High-quality, transparent data

- Ensure a comprehensive range of data insights are routinely collected and made available to stakeholders to support good and timely data-driven decision making

Create a nimble and flexible VET system

- Recognise the unique role of Learn Locals through appropriate funding and frameworks

- Fully fund Foundation Skills courses

- Create a compliance system that ensures quality but does not overburden VET providers

- Bridge the funding gap between the ‘volume of learning’ set by the Australian Qualifications Framework and the nominal hours the Victorian Government funds

- Bolster government funding to enable VET providers to develop and deliver courses that meet industry need in rural and regional areas

- Remove demand-driven funding and ensure VET providers have sufficient resources to support student retention

Increase opportunities for lifelong learning

- Remove restrictive eligibility criteria for government subsidised training, including the ‘two-course’ rules and the ‘upskilling’ rule

- Ensure micro-credentials are government subsidised

- Ensure micro-credentials can lead to pathways to full qualifications

- Remove dual enrolment eligibility restrictions for young people at school who want to do a VET course outside of VETiS, so they can access Skills First funding

- Provide secondary school teachers with greater opportunities to ensure their industry skills and knowledge are up-to-date

- Provide learners with clear and up-to-date information about career pathways and opportunities available through the VET system

Provide students experiencing disadvantage with tailored, wrap-around supports

- Immediately secure funding for the Skills First Reconnect program which is due to end in December 2020

- Give high-needs learners and people experiencing disadvantage access to bursaries or scholarships to pay for hidden costs and help afford the basics

- Boost retention by expanding programs that provide high-needs learners and people experiencing disadvantage with intensive support, including for literacy and numeracy, as well as access to a youth worker or support worker

- Create a Youth Jobs Plan

Give students the skills and capabilities industries and employees need

- Move away from competency-based training to focus on teaching students the capabilities they need

- Provide tailored and individualised support for young people in the justice system

Invest in industries that yield high jobs growth

- Systemically embed traineeships, apprenticeships and student placements in the VET system

- Invest in the capacity of priority industries – including the community services industry – to increase student placements, including scaling-up current examples of innovative practice

- Provide State Government wage subsidies for trainees, to create a pipeline of new workers in priority industries

- Enable industry advisory groups to leverage the best insights from sectors, by funding the participation of industry representatives

High-quality, transparent data

Recommendation

- Ensure a comprehensive range of data insights are routinely collected and made available to stakeholders to support good and timely data-driven decision making

This section of the submission responds to Terms of Reference 1.

Government policy makers, funders and regulators, industry representatives and VET providers need access to timely and high-quality data to understand the education and training needs of Victorians and to develop and implement the right system-level and institutional-level responses.

Research evidence and data can support industries to improve service delivery, outcomes for services users and harness innovative practice[3]. It also provides industry and government a mechanism to make informed decisions about how to address skills and capability gaps, and where to direct resources.

Students also need access to data to assist their decision-making – for example, students would benefit from data insights about high jobs growth industries and training options.

The Victorian Government currently places caps on commencements for specific courses, and has introduced caps on some Free TAFE offerings. Providing stakeholders with access to the data that underpins this decision-making would assist providers (for example) to understand these decisions and inform their organisational strategy and operational responses.

Investing in high quality data collection enables key stakeholders to better understand the impacts and any unintended consequences of policy decisions. For example, the impact current funding rates for Foundation Skills and Certificate I and II courses has on availability and offering of these courses, or, any consequences of the reduction in eligibility waivers for accessing Skills First funding.

Create an accessible, nimble and flexible VET system

An accessible system

Recommendation

- Recognise the unique role of Learn Locals through appropriate funding and frameworks

- Fully fund Foundation Skills courses

This section of the submission responds to Terms of Reference 4 and 7.

Current funding mechanisms enable government to use subsidies to control enrolments and influence student pathways into certain occupations and industries. While the vocational education and training system has a key role to play in preparing Victorians for work, there is a risk that, in principally focusing on vocational education and training as a means by which to build ‘human capital’ for industry, we minimise the inherent social value of vocational education and training. For many highly-disadvantaged learners, participating in vocational education and training also helps build social capital, which benefits not only the individual, but their community. This is why it is so important that the vocational education and training system is accessible.

Government subsidies play a key role in making the system accessible.

The Victorian Government’s Skills First program enables eligible students to gain access to government subsidised training. However, it has not delivered on the promise that “funding subsidies will reflect the real cost of qualifications”[4]. This can impact a VET providers’ ability to provide, or recover the costs of providing, additional or more intensive supports to students to support their retention and engagement. It can also impact provision of quality courses that assist students in gaining high level skills and knowledge.

For example, Learn Local providers, which have a significant focus on supporting disadvantaged learners and learner wellbeing, are often constrained by low subsidy rates for Foundation Skills, Certificate I and Certificate II courses.

Learn Locals offer pre-accredited and accredited training and provide community-based learning environments that can be more accessible for people who find larger institutions such as TAFEs overwhelming, or as a soft entry point into the education system. Local environments and smaller class sizes can help overcome barriers including for people with limited educational experience, those for whom English is not their first language, or those who have had poor experiences with education in the past.

This Review provides an opportunity to recognise Learn Locals’ unique value and social impact, and to ensure that system reforms address critical funding challenges for not-for-profit community-based providers.

An example of the challenges facing providers is the level of funding subsidy for Foundation Skills courses. Foundation Skills courses provide an important gateway for people who have left school early, without the requisite literacy or numeracy skills, or who are experiencing other forms of disadvantage, to learn fundamental skills that can set them up for further training or employment. At the same time, students build greater confidence and connection to their social environments and communities. There are also generational impacts: for example, by developing foundational language, literacy and numeracy skills, parents can, in turn, support their children with their language and literacy.

For many Foundations Skills students, flexible and tailored support is key to their engagement and success.

From a provider’s perspective, the hourly funding rate of just $7 per hour – a rate that has not changed in years – gives them less capacity to cover the additional resources it takes to intensively support struggling learners. Low government subsidies also impact providers’ ability to offer some Certificate I or Certificate II courses.

For some learners, the low government subsidies for Foundation Skills courses and some Certificate I and II courses put these opportunities out-of-reach, creating barriers to accessing higher-level training and employment participation.

As Victoria moves to a COVID-safe environment, the funding challenges are likely to be amplified. For some high-needs learners who have struggled in the online learning environment, there may be a need for increased face-to-face support in the recovery phase. Unless the hourly rate of funding is increased, providers’ ability to respond to those needs and sustain student engagement will be constrained.

A more flexible system

Recommendations

- Create a compliance system that ensures quality but does not overburden VET providers

- Bridge the funding gap between the ‘volume of learning’ set by the Australian Qualifications Framework and the nominal hours the Victorian Government funds

- Bolster government funding to enable VET providers to develop and deliver courses that meet industry need in rural and regional areas

- Remove demand-driven funding and ensure VET providers have sufficient resources to support student retention

This section of the submission addresses Terms of Reference 4, 5 and 7.

Current funding models are prohibitive and do not allow for sufficient flexibility to enable innovative practice and new vocational education models, or for courses to be responsive to industry need[5]. Key issues include:

- Significant funding is spent on meeting compliance and to pay for overheads, reducing the funding available for other resources including course development. This can be a significant issue for small Learn Local providers in delivering accredited training.

Compliance has an important role in ensuring a high-quality VET system and protecting students from being taken advantage of by ‘dodgy’ providers. However, a balance needs to be struck to ensure compliance is not so onerous and resource-intensive that it is prohibitive and prevents flexibility, responsiveness and innovation.

- There is a discrepancy between the ‘volume of learning’[6] the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) sets for qualification levels and the number of hours that the Victorian Government funds per course. For example, a Certificate III in Community Services requires between 1200 – 2400 hours as set by the AQF[7], but the Victorian Government only funds a maximum of 620 hours. This impacts course design and delivery.

- Demand-driven funding that ‘follows’ the student distorts the incentive and ability of VET providers to cater to ‘thin markets’, creating access and equity issues. This has a particularly significant, adverse impact on course offerings in rural and regional areas.

The Victorian Government funds the Regional and Specialist Training Fund (RSTF) (which is currently under evaluation[8]) to help VET providers to bridge the gap in the training market and meet the specific skills needs for particular regions. Despite this investment, VCOSS members report there are still gaps in available VET courses in rural and regional areas. Additionally, the courses offered don’t always reflect job opportunities in the region. This creates greater disparities in access and opportunities for people in rural and regional areas to train, reskill or upskill, and to access job opportunities in their local communities without having to relocate for training.

- Currently, as funding is attached to enrolments and drip-fed to VET providers throughout the duration of a course based on the student’s ongoing engagement, this means that:

- VET providers have an incentive to boost enrolments in popular courses, irrespective of whether there is industry demand for these skills and irrespective of whether there is a viable employment pathway for graduates.

- Some VET providers may not have the resources to provide wrap around supports that assist struggling students to overcome barriers to improve retention.

- Another challenge is that, because funding ‘follows’ the student, smaller providers do not have the same resources that larger providers can use to support students and drive up retention.

These constraints not only directly impact students’ ability to access the best courses for their needs, but impacts the ability of teachers to be responsive and innovative, and provide relevant, high-quality teaching.

Victoria’s VET system needs a new funding model that moves away from demand-driven funding and provides sufficient flexibility for VET courses and teachers to be responsive and ensure equitable access to a range of opportunities for all students, regardless of where they live.

Increase opportunities for lifelong learning

Recommendations

- Remove restrictive eligibility criteria for government subsidised training, including the ‘two-course’ rules and the ‘upskilling’ rule

This section of the submission will respond to Terms of Reference 4 and 7.

In order for the VET system to be truly responsive to the changing world of work and the growing reality that people are more likely than ever to change careers, restrictive eligibility criteria for access to Skills First funded training needs to be addressed.

Two-course rules

Students should be able to access affordable training options that best meet their needs, regardless of their circumstances.

Current eligibility criteria mean students can only:

- commence a maximum of two government-funded courses in a calendar year

- undertake a maximum of two government-funded courses at any one time

- commence a maximum of two government-funded courses at the same level in their lifetime.

These restrictions only factor course commencement, not completion. This is a problem in itself – if a student enrols in a government-subsidised VET course and attends one day before withdrawing, this counts as a course commencement.

In addition, students can only commence one Free TAFE course with the tuition fee waiver.

These rules create barriers to accessing training that disproportionately impact high-needs learners and people experiencing disadvantage. For example, experiences of homelessness, mental ill health, family violence, or changed caring responsibilities may impact a student’s ability to complete a course. This means some learners may ‘use up’ their two course commencement at one level in a lifetime, making access to government funded training and meaningful employment unachievable.

The rules also fail to respond to contemporary labour market needs. The two-course rule creates barriers to re-skilling or upskilling for Victorians who are seeking to re-enter the workforce and/or who are seeking to change careers, with a disproportionate impact on women who are returning to work after having children. These rules reduce economic participation and do not support lifelong learning.

Anecdotally, VCOSS members report students may also enrol in a full course to gain access to the government subsidy but with the intention of only obtaining a micro-credential within the qualification. The complex nature of the VET system means students are not always aware of the ‘two-course’ rule restrictions, or they may not fully understand the implications of using one subsidised course to complete a discreet unit.

Upskilling rule

Currently, students cannot access a subsidised training place to gain new skills and retrain if their nominated course does not lead to a ‘higher’ qualification. The exception to this rule is if a student can obtain an eligibility waiver.

Currently, eligibility waivers for TAFEs and Learn Locals are capped at 10 per cent of student enrolments per calendar year. This means only 10 per cent of enrolled students who commence a course (in contrast to completing a course) are able to access an eligibility waiver to gain a subsidised training place. This has recently been reduced from 20 per cent. Under this restriction, if a student drops out, TAFEs and Learn Locals are unable to offer a subsidised place to another student who requires an eligibility waiver.

Policy settings including the two-course rules and access to subsidised training, alongside a lack of awareness and representation of careers and training options obtained through the VET system, including in secondary schools, has led to a mismatch between skills obtained and jobs available. University pathways are often the ‘default’ post-secondary pathway for secondary school students[9].

There is a pressing need for not only better career information, but for eligibility criteria for subsidised training places to be flexible and accessible so Victorians can retrain and upskill at any point in their lives. This will be particularly relevant as Victoria transitions to a COVID-19 recovery phase and more Victorians decide to retrain as unemployment rates rise.

Upskilling also enables workers to gain specific skills and knowledge to support their existing work, or to transition between sectors. For example, a professional with a Bachelor of Psychology or Social Work may wish to undertake a Certificate IV in Alcohol and Other Drugs to gain specific knowledge and expertise to deepen their practice and provide specialised support.

‘Upskilling’ rules undermine the importance and value of VET qualifications. Policies that restrict learners from obtaining a government-subsidised training place for a VET course because they have an existing Bachelor degree from university structurally undermines the value of VET and perpetuates the problem of VET qualifications being seen as ‘lower’ qualifications or skills relative to those gained through university education.

These rules also create barriers to having a workforce that is adaptable and flexible and impacts workforce transitions, including into high job growth areas such as community services.

Recommendation

- Ensure micro-credentials are government subsidised

- Ensure micro-credentials can lead to pathways to full qualifications

This section of the submission will respond to Terms of Reference 2, 4 and 7.

Employers increasingly regard micro-credentials as an effective way to bridge skills gaps in the workforce[10]. While micro-credentials have the potential to help Victorians gain the right skills and capabilities and may improve access to reskilling and upskilling, any changes made need to ensure they do not undermine the integrity of VET qualifications and qualified workforces.

The role, intent and purpose of micro-credentials should be clearly defined and understood as a tool to support lifelong learning and support upskilling and workforce transition. VCOSS understands this work is currently underway as part of the VET Reform Roadmap[11].

Key aspects that should inform the role of micro-credentials that is currently taking place at the national level include:

- Ensuring the funding model is not prohibitive and does not disadvantage access for low-income learners (i.e. the costs are not pushed back onto students as many short courses or micro-credentials currently are)

- Ensuring micro-credentials do not undermine the professionalism of the community services sector, for example, by being used as an entry point into the sector without pathways to full qualifications.

In response to COVID-19, the Commonwealth Government has announced subsidised university short courses for priority areas[12], alongside new skill sets for the aged and disability sectors[13]. It is important that any crisis response to ensure vulnerable members of the community receive the care and support they deserve, does not set a precedent to forego full qualifications as the community moves into the COVID-recovery phase.

Full qualifications should remain the way skills and knowledge are developed[14], with micro-credentials providing a pathway for learners with existing skills to obtain discreet new skill-sets to support changing industry need.

Recommendation

- Remove dual enrolment eligibility restrictions for young people at school who want to do a VET course outside of VETiS, so they can access Skills First funding

- Provide secondary school teachers with greater opportunities to ensure their industry skills and knowledge are up-to-date

VCOSS highlighted key areas for reform between the secondary schooling and VET systems in our submission to the Review into Vocational and Applied Learning Pathways in Senior Secondary Schooling[15]. These include:

- dual enrolment constraints that prohibit enrolled secondary school students from enrolling in a government-subsidised VET course (unless part of VET delivered in school or a school-based apprenticeship or traineeship). This acts as a particular barrier for young people who may be experiencing disadvantage or be at risk of disengaging from school.

- some teachers have only completed a short professional development course in the VET Delivered in Secondary School subject they deliver, while others have extensive industry experience. This can impact the quality of the education young people receive.

Recommendation

- Provide learners with clear and up-to-date information about career pathways and opportunities available through the VET system

This section will respond to Terms of Reference 6.

The VET system is complex to understand and difficult to navigate. VCOSS members report challenges for students in secondary school and post-secondary school in understanding the range of career pathways, jobs and industries available to them.

To improve pathways and connections between educational institutions and providers, information needs to be accessible, easy to navigate, and well promoted. The Victorian Skills Gateway has some important foundational information to help guide students and prospective students about course options and career pathways, however, it is underutilised, has a number of inaccuracies and does not appear to be widely known.

A comprehensive and up-to-date website would make it easier for students, families and carers, and career practitioners to understand the VET system and how it interacts with other education and training pathways, as well as career opportunities. It should include comprehensive pathways that individual courses or units can lead to, ways to transition to and from educational institutions to gain the skills students need, what these different institutions are and the role they play within the education and training eco-system, and show aspirational career pathways that a qualification can lead to. This should include a platform to showcase the achievements and success stories of individuals from a range of industries, highlighting the varying pathways taken – stepping as far back as the opportunities of undertaking VCAL or VET in secondary school.

Clearer information about career pathways and opportunities through the VET system also need to be communicated and promoted in secondary schools so young people can align their strengths and interests with opportunities that sit beyond university education.

Provide students experiencing disadvantage with tailored, wrap-around supports

recommendations

- Immediately secure funding for the Skills First Reconnect program which is due to end in December 2020

- Give high-needs learners and people experiencing disadvantage access to bursaries or scholarships to pay for hidden costs and help afford the basics

- Boost retention by expanding programs that provide high-needs learners and people experiencing disadvantage with intensive support, including for literacy and numeracy as well as access to a youth worker or support worker

This section will respond to Terms of Reference 2.

To create an inclusive and thriving society and to meet the skills and capability needs of industries, employers, government and the community, Victorian industries need diverse workforces that reflect the community.

Everyone benefits from diversity and inclusion in the workplace[16], however, there are some cohorts who experience a range of barriers in accessing and engaging in the education and training needed to find meaningful employment.

VET is an important pathway to employment for people experiencing structural disadvantage. These cohorts include people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people with disability, people with lived experience (for example, of mental ill health or family violence), who live in rural and regional areas and those from low socio-economic backgrounds.

Their experience of disadvantage may create barriers to finishing their studies[17] and students may require extra support to improve retention and course completion. Financial aid and personalised support makes a difference[18]. Examples of personalised support that reduce barriers include dedicated mentoring, intensive literacy and numeracy support, assessment adjustments, counselling or warm referrals to a range of social services (such as family violence or housing and homelessness agencies)[19].

Reasonable adjustments, including adjustments to assessments and course material, are particularly important for students with disability to ensure they are able to participate and engage in their education on the same basis as their peers.

A range of initiatives should be considered to remove barriers to participation and support course completion. These could include bursaries or scholarships to financially support students to cover hidden costs and to support those who can’t afford the basics.

The Victorian government initiative ‘Skills First Reconnect’ program is vital in supporting high-needs learners and individuals who are long-term unemployed to reengage with education and training[20]. However, VCOSS understands funding for this program is due to finish at the end of 2020. Given the time it takes to engage with eligible participants, VCOSS members report some Reconnect providers are not taking on new referrals after the end of June 2020. Skills First Reconnect forms a vital connection with another Victorian Government initiative, the Navigator program. This program is designed to provide intensive case management to reengage young people aged 12 to 17 back into education. As Navigator is oversubscribed and subject to long-wait lists, young people that may otherwise fall through the cracks are picked up through Skills First Reconnect. While Skills First Reconnect services the community from ages 17 to 64, VCOSS members report young people particularly benefit.

In the context of COVID-19, programs like Skills First Reconnect need a funding boost more than ever, as well as funding security moving forward, to ensure disadvantaged and high-needs learners get the support they need to reconnect with education and training pathways.

Future Social Service Institute approach

The Future Social Service Institute (FSSI) is a partnership between VCOSS and RMIT University, supported by the Victorian Government. FSSI drives innovation in education, training and applied research to enable the growth and transformation of the social services sector.

Some of the ways it does this include:

- Developing and piloting new educational approaches, training and workforce development models, and improved pathways

- Developing, testing and evaluating models to improve students’ experience of learning, including improved retention

- Developing innovative new curriculum products to strengthen service provision.

An example relevant to the Victorian Government’s review into Skills for Victoria’s Growing Economy is the Certificate III in Individual Support that FSSI is currently delivering

These courses incorporate wrap around support that provides holistic and effective support for disadvantaged members of the community. The model is based on building on the capabilities of people and communities rather than a punitive welfare model, by providing up-front investment that leads to positive longer-term outcomes in supporting people into a career and increasing workforce participation. For many of these students, whose backgrounds vary across age and cultural backgrounds, they may not have completed or engaged in their studies without a reinvestment model that provides the supports they need to thrive.

Key elements that lead to effective support and positive long-term outcomes include:

- Collaboration between key stakeholders that support the wellbeing of students and their engagement in the course, including VET providers and teachers, wellbeing supports, and a supporting organisation who acts as the ‘backbone’ and navigates the ‘joining up’ piece in collaboration. This organisation needs to have trust and credibility

- Building additional resources into the model to be responsive to a particular student’s or cohort’s needs

- For example, not every student may need literacy and numeracy support, however, for those who do, it will be a vital part of their success in completing the course. Integrating additional resources for this kind of support within a substantive qualification rather than redirecting every student to a Foundation Skills course can improve retention and provide an extra draw-card for students as the qualification leads to clear employment pathways

- A financial support fund to assist students in overcoming additional barriers throughout the course, such as covering the cost of travel, or providing a digital device, is another example of integrating additional resources to be responsive to student’s needs

- Provision of a support worker, youth worker, or life coach, to support students, maintain their engagement in study, and to help navigate complex parts of the system including enrolment and student placements or traineeships

- Curriculum co-design to take a person-centred approach and to facilitate rich discussion and development of ‘complex’ skills. For example, creating new units or modules that use videos as a discussion prompt that enables students to focus on the ethics and human rights implications of their studies. This can be particularly important in the community services sector.

This kind of model can significantly improve retention rates. For it to be successful, it needs to be appropriately resourced, including for coordination, and additional funding for VET providers and teachers who provide significant support beyond their paid hours.

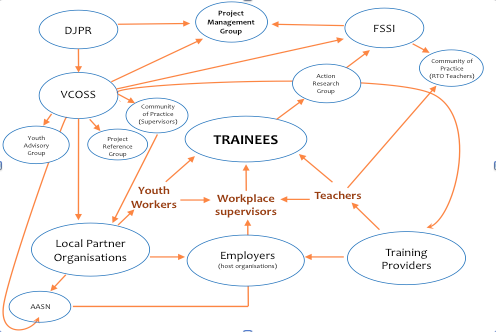

Community Traineeship Pilot Program

The Community Traineeship Pilot Program managed by VCOSS and funded through Jobs Victoria supports young people experiencing barriers to labour market participation to undertake a community services qualification, while supporting community service organisations to host traineeships and meet their future workforce needs[21].

Both trainees and employers are provided with support through a Local Partner Organisation (LPO), which employs a youth worker and works directly with trainees to keep them engaged in the program[22]. The role of the youth worker is vitally important in supporting the trainees to navigate and overcome challenges that arise during their placement – for example, mental ill health, family violence or homelessness. Youth workers attend the TAFE classes with trainees, and are also available to support employers and workplace supervisors to navigate any difficult conversations with trainees, for example, not arriving to work on time.

In addition, LPOs manage a Flexible Wrap Around Support fund that can be used to reduce barriers to engagement. This fund has been used to pay for things such as a myki top-up or money for petrol to get to work through to emergency accommodation or groceries.

This traineeship model is designed to foster collaboration between a range of key stakeholders to make sure the young people don’t fall through the cracks. These key stakeholders include employers, LPOs, youth workers, VET providers and teachers, and the trainees, who are all working together. At the same time, this model has a strong focus on peer support by bringing the trainees together and helping them connect, for example by placing the trainees in classes run specifically for them.

There is immense and long-lasting value in undertaking a holistic approach to support young people out of disadvantage and into meaningful career pathways by providing up front resources (both human and financial). The long-term costs of not providing this support and not ‘catching’ young people who may have disengaged from education and training or are experiencing long-term unemployment, can have significant and long-lasting social as well as economic impacts[23]. In other words, the cost of not providing this support is much too high.

Community Traineeship Pilot Program concept map demonstrating how key stakeholders interact

The national rate for traineeship retention is approximately 50 per cent[24]. The Community Traineeship Pilot Program saw a retention rate of 80 per cent for the first cohort, with more than 50 per cent gaining further employment with their employer post traineeship completion.

Early learnings from the program indicate not only high rates of retention but increased levels in the resilience of the young people who participated in the program, as well as higher levels of independence in proactively seeking support, and positive and empowering changes to their identify. The Future Social Services Institute continues to undertake the developmental evaluation component of this program.

Future considerations for this model include providing additional funding to VET providers to resource the additional collaborative aspects of the program. With adequate funding for VET providers, this model can be place-based by supporting young people to undertake training with a VET provider in their local area.

Recommendation

- Create a Youth Jobs Plan

Youth unemployment is stubbornly high and already high levels of unemployment and under-employment are likely to be exacerbated, with young people are being disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic[25].

To support a renewed VET system, the Victorian Government can create a Youth Jobs Plan to support young people facing increasingly precarious employment opportunities. Co-designed with young people and their communities, this plan can bring together government, educators, jobseeker supports and employers to reduce Victoria’s high youth unemployment rate. A Youth Jobs Plan could support existing frameworks such as the recently released Youth Justice Strategic Plan that calls for young people in Youth Justice to be linked in with mentoring and training as well as support to increase job readiness[26].

A Youth Jobs Plan can leverage the historical work of Local Learning and Employment Networks (LLENs) in providing brokerage and innovation to help disadvantaged young people successfully navigate into a career. For instance, LLENs bring together employers, school, training providers and community services to strengthen young people’s education, training and employment outcomes. LLENs, who now primarily facilitate Structured Workplace Learning for secondary school students, have a proven track record of supporting their community with place-based solutions to catch young people who may otherwise fall through the cracks. However, to facilitate this work, LLENs would need to be provided with the resourcing to effectively support young people under a Youth Jobs Plan.

Give students the skills and capabilities industries and employees need

Recommendation

- Move away from competency-based-training to focus on teaching students the capabilities they need

This section will respond to Terms of Reference 2 and 5.

The VET system needs to be equipped to prepare people of all ages for the changing world of work, including those in transitioning industries and people seeking to upskill, beyond specific skills designed for a specific task. This will require a significant shift from competency-based training towards capabilities. These changes will support the VET system to meet the needs of industry, employers, government and the community into the future. They will also support teachers to better prepare job-ready graduates.

There is growing agreement that capabilities such as the ability to respond to opportunities and problems creatively and experimentally are vital for the future world of work[27], and change needs to start taking place in schools as well as further education and training systems. These skills, sometimes called ‘soft skills’ but here referred to as ‘complex skills’, are hard to learn and hard to teach – however, they are vital to creating a nimble and flexible workforce that will be able to adapt to changing workforce need[28].

Competency-based training can minimise the importance of ‘complex skills’, and course design, funding and broader compliance issues restrict the ability of VET teachers to be innovative as they do not allow teachers the time to teach students these more complex capabilities.

Competency-based training can also miss the broader educational benefits of undertaking further training beyond job-readiness and employment outcomes[29]. For example, a student may wish to undertake a foundation level course that will not lead to an employment outcome, but which will improve their language and communication skills. This can in turn help parents assist their children with learning, creating significant flow-on effects, and foster greater social and community connectedness.

Provide people in youth justice centres with meaningful education

Recommendation

- Provide tailored and individualised support for young people in the justice system

Education is a key mitigating factor to poor life-outcomes and long-term unemployment[30]. There is a disproportionate representation of young people in the juvenile justice system who were suspended or expelled from school, and the majority of people in the criminal justice system have not finished school[31].

Many young people in youth justice centres have experienced high rates of abuse and trauma, and there are high rates of intellectual disability in the youth justice cohort[32]. These young people often need tailored responses to their learning needs. This should include environments that reflect similar learning needs and support to ascertain the level and abilities of each young person so they get the support they need to learn.

VCOSS members report education offerings for young people in youth justice centres, including those undertaking the Victorian Certificate of Applied Learning, is often constrained by security or resourcing decisions. While these are important considerations, young people in youth justice centres, including those on remand, need to feel safe and appropriately supported to engage in education.

VCOSS members also report young people in justice centres need access to more hands-on applied learning opportunities, generally undertaken through the VET system, to improve their skills and opportunities for when they exit the system. There is also evidence that this is a meaningful and proven approach for older people in the justice system[33].

Invest in industries that yield high jobs growth

Recommendation

- Systemically embed traineeships, apprenticeships and student placements in the VET system

This section will respond to Terms of Reference 3.

The deep and ongoing connection between the VET system and industry is critical to ensuring vocational education and training is able to equip learners with the vital skills and capabilities required to meet areas of high job growth.

This Review is an opportunity to recast the way in which connections are made between schools, students (both secondary school and VET) and employers.

The value of on-the-job training is significant. It can be an effective way to teach and to learn, can lead to better alignment with the skills sought after in the workplace or industry, and gives students the opportunity to obtain an understanding of the workplace[34].

Internationally, countries such as Germany and Switzerland have dual-track training systems in secondary schools that embed traineeships and student placements within large employers. Students undertake “in-company training” for three to four days per week alongside school education. Training undertaken in a company teaches students specific profession-related skills, which is supplemented by several weeks of training from broader industry bodies to fill any gaps in the specialised training, while studying the essentials (such as literacy and numeracy) at school[35]. This helps meet skills demand while matching careers with student capabilities and interests.

There are key elements of these models that could be adopted in Victoria to strengthen the partnerships between education settings and industry, taking place both at a secondary school level and within the VET system for post-secondary students.

The VET system in Australia consults with industry, such as the Victorian Skills Commissioner, however, there are ongoing concerns that the VET system can be slow to respond to industry need. There are also concerns that there is a deficit in the diversity of representation of industry in consultations that shape training products, which can at times lead to courses allocating vital subjects as electives rather than core subjects. VCOSS members report many organisations do not have the resources to invest in the time needed to meaningfully engage in an ongoing way.

Systemically embedding traineeships, apprenticeships and student placements in the VET system could motivate employers to take a more active role in supporting the training of their potential future workforce. At the same time, structural change would address existing challenges for students in finding suitable placements to complete their qualifications. It would also motivate more employers and industry to have a stake in ensuring courses are up-to-date and relevant to industry need to support the relevance of the on the job training they are providing to students.

This model would enable students to earn a wage while studying, which means many students can finish their qualification with no debt, have money in their pocket, and be in high demand for their skills. This could be an appealing and motivating factor for young people pursuing this pathway in secondary school, and uplift the reputation and appeal of the VET system more broadly. Added benefits include breaking down financial barriers to studying, including those who may be seeking to retrain, and supporting business with capable trainees and apprentices.

VET providers would also need to be funded to deliver on these changes by updating course design.

Recommendations

- Invest in the capacity of priority industries – including the community services industry – to increase student placements, including scaling-up current examples of innovative practice

- Provide State Government wage subsidies for trainees, to create a pipeline of new workers in high jobs growth industries

- Enable industry advisory groups to leverage the best insights from sectors, by funding the participation of industry representatives

This section will respond to Terms of Reference 3.

The community services industry is not only a large employer in Victoria, but is one of the state’s fastest growing industries. With a range of social policy reforms including the roll out of universal three-year-old kinder, family violence, mental health, aged care and NDIS reforms, the community services industry will require a steady flow of job-ready graduates to meet workforce and community demand for vital services[36].

Student placements and traineeships are an integral part of ensuring students gain the appropriate skills and knowledge to be job-ready. There is growth across the education sector from senior secondary schools, to universities, and VET providers, to provide students with an opportunity to undertake some form of student placement. For the community services industry, this is also being fuelled by the Victorian Government’s Free TAFE initiative.

The community services industry is predominantly publicly funded[37] and, in this way, differs from other industries. Supporting students to engage in placements, traineeships or apprenticeships takes time and costs money. Private sectors who have additional resources obtained through selling their services are more likely to have the capacity to invest in the extra staff and supervision training it takes to support traineeships, apprenticeships or student placements. VCOSS members report many community service organisations face staff shortages and have limited capacity to accommodate student placements due to limited resources. This is further compounded by high-demand for services and short-term or inadequate funding which contributes to high staff turn-over.

To create workforce growth and maintain and enhance workforce quality, the community services industry needs government investment to support a pipeline of workers with a wide range of skills. Government investment is needed to support the sector to ensure appropriate quality and safeguarding – for example, ensuring services commissioned by government are funded such that there are adequate positions for supervision and investment in the professional development of the workforce (for example, supervision training).

Wage subsidies also play an important role in supporting community service organisations to take on trainees. However, current subsidies or incentives at the Commonwealth level are insufficient to support community sector organisations to meet the costs of a traineeship wage. The Community Traineeship Pilot Program funded by Jobs Victoria, provides $3425 upfront to an employer when they employ a trainee. This, in combination with Commonwealth subsidies makes a more realistic contribution to meeting the costs of employing and supporting a trainee. These subsidies have often been a deciding factor in whether or not an organisation has been able to commit to taking on a trainee in this program.

The Victorian government should work alongside the Commonwealth government to consider their joint role in ensuring community sector organisations have access to genuine wage subsidies to help grow a pipeline of workers.

COVID-19 has proven the VET sector can respond rapidly to address an identified skill need[38], however, organisations need the time and resources to contribute during and beyond times of pandemic. Resourcing constrains the capacity of smaller and mid-size community sector organisations to participate in relevant industry stakeholder groups that provide input into national training packages. This can have significant consequences for the formation and relevance of qualifications, including whether or not vital subjects are listed as ‘core’ parts of a qualification, and whether or not qualifications are ‘fit-for-purpose’ for smaller organisations. The government should fund a diverse range of community services organisations (of varying sizes and which cater to key cohorts) within each sub-sector to release appropriate staff (including frontline staff) to attend industry consultations.

Programs such as Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence Work project, and pilots like the new Higher Apprenticeships Pilot Project that supports the social services sector workforce to increase leadership and management capacity and capability[39] will be important in supporting the growing community sector.

Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence Work project

Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence Work project[40], now in its third year, acknowledges the importance of addressing workforce supply challenges and supporting organisations with funding, training and other resources to build the pipeline of workers needed[41].

Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence Work is a project funded by Family Safety Victoria and is designed to:

- Strengthen pathways for new workers into the specialist family violence and community services sector

- Build capabilities of students and graduates to be more “work-ready”[42].

In 2019, VCOSS invited Expressions of Interest for community service organisations on behalf of DHHS and Family Safety Victoria (FSV) as part of Stage 2 of the project. Successful participating organisations received a range of supports to build their organisation’s capacity and capability to support student placements and contribute to a pipeline of future workers. To facilitate this, organisations received:

- a funding support package to contribute to the costs associated with participating in the project (which could include costs associated with staff training and backfill)

- dedicated support from a project Capability Building Coordinator who:

- assists organisations to build their capacity to provide student placements (including use of a web-based administration system to support placement management)

- supports organisations to develop formal partnerships with education providers (VET and universities)

- works with staff and training providers to ensure all identified staff attend training to build their capacity in supervision and increase their understanding of family violence practice. This can include identifying any additional training options where relevant

- supports supervisors to build their supervision capability and understanding of family violence practice through facilitation of a Community of Practice

- fosters a workplace culture of learning by supporting the organisation’s implementation of the Best Practice Clinical Learning Environment Framework and relevant tools

- introduces and supports the implementation of the ‘Orientation to Family Violence Practice Guidelines’.[43]

Government could adapt and scale-up this model to support other growing community services industries.

[1] L Wheelahan, G Moodie, E Lavigne & F Samji, Case study of TAFE and public vocational education in Australia: preliminary report, Education International Research, October 2018, p. 13

[2] Foundation for Young Australians, The New Work Order, 2015.

[3] VCOSS, 10 Year Community Services industry Plan, August 2018.

[4] Victorian Department of Education and Training, Skills First: Real training for real jobs, The Education State, August 2016, p.5.

[5] A Jones, Vocational education for the twenty-first century, University of Melbourne, August 2018.

[6] Australian Qualifications Framework Council, Volume of Learning: An Explanation, May 2014.

[7] “The volume of learning allocated to a qualification should include all teaching, learning and assessment activities that re required to be undertaken by the typical student to achieve the learning outcomes.” Australian Qualifications Framework Council, Volume of Learning: An Explanation, May 2014, p.1.

[8] Victorian Department of Education and Training, Regional and Specialist Training Fund, <https://www.education.vic.gov.au/training/providers/funding/Pages/rst.aspx>, accessed 26 May 2020.

[9] Youth Action, A NSW for Young People: Beyond 2019, 2019.

[10] NCVER, Focus on Micro-credentials, December 2018, <https://www.voced.edu.au/focus-micro-credentials>, accessed 28 May 2020.

[11] Australia Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment, VET Reform Roadmap, <https://www.employment.gov.au/vet-reform-roadmap>, accessed 27 May 2020.

[12] Federal Minister for Education, ‘Short courses providing new skills to Australians’, Media release, 14 May 2020.

[13] Federal Minister for Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business & Federal Assistant Minister for Vocational Education, Training and Apprenticeships, ‘New skill sets to support aged and disability sectors’, Media release, 21 May 2020.

[14] Business Council of Australia, Future-proof: Australia’s future post-secondary education and skills system, August 2018, p.39.

[15] VCOSS, An aspirational Vocational and Applied Learning System, April 2020.

[16] Deloitte Access Economics, The economic benefits of improving social inclusions, a report commissioned by SBS, August 2019.

[17] NCVER, VET Qualification completion rates 2017, August 2019.

[18] Future Social Service Institute, Submission to Joint Standing Committee on National Disability Insurance Scheme – Market Readiness, 8 March 2018.

[19] Youth Action – Uniting – Mission Australia, Vocational Education and Training in NSW: Report into access and outcomes for young people experiencing disadvantage – Joint report, February 2018.

[20] Victorian Department of Education and Training, Skills First Reconnect program, <https://www.education.vic.gov.au/about/programs/Pages/reconnect-program.aspx>, accessed 26 May 2020.

[21] VCOSS, Unlimited Potential. CTPP Employer VET Flyer, viewed at https://vcoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/CTPP-Employer-VET-Flyer-Web-Upload.pdf

[22] For more information about the program structure and funding incentives, see VCOSS, Jobs Victoria Community Traineeship Pilot Program: Expressions of Interest for Host Organisations Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) viewed at https://vcoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/v2-FAQ-Document-for-EOIs.pdf

[23] A Powell, F Salignac, A Meltzer, K Muir & M Weier, Background report on young people’s economic engagement, Report for Macquarie Group Foundation, Centre for Social Impact, February 2018.

[24] NCVER, VET Qualification completion rates 2017, August 2019.

[25] S Dimov, T King, M Shields & A Kavanagh, ‘The young Australians hit hard during COVID-19’, Pursuit, University of Melbourne, 25 May 2020.

[26] Victorian Department of Justice and Community Safety, Youth Justice Strategic Plan 2020-2030, May 2020.

[27] Deloitte Access Economics, Soft skills for business success, DeakinCo., 2017.

[28] OECD, Future of Work and Skills, Paper presented at the 2nd Meeting of the G20 Employment Working Group, 15-17 February 2017.

[29] S Hodge, The problematic role of CBT in Australian VET, University of Melbourne, August 2018.

[30] KJ Hancock & SR Zubrick, Children and young people disengaged from school, University of Western Australia, June 2015 (updated October 2015), p.5.

[31] J Watterson & M O’Connell, Those who disappear: The Australian education problem nobody wants to talk about, University of Melbourne, Melbourne Graduate School of Education, Report No. 1, 2019.

[32] J White, K Te Riele, T Corcoran, A Baker, P Moylan R Abdul Manan, Improving educational connection for young people in custody, Final Report, Victoria University, University of Tasmania, Deakin University, June 2019.

[33] B Collins, ‘Prison education program helps Kimberley inmates learn how they can get out and stay out’, ABC Kimberley, 31 May 2020.

[34] Deloitte Insights, ‘The path to prosperity. Why the future of work is human’, Building the Lucky Country #7, 2019.

[35] M Bax, ‘How does dual training work?’, Bildungs Perten Netzwerk, <https://www.bildungsxperten.net/wissen/wie-funktioniert-eine-duale-ausbildung/>, accessed 6 April 2020.

[36] VCOSS, 10 Year Community Services industry Plan, August 2018.

[37] N Cortis & M Blaxland, The profile and pulse of the sector: Findings from the 2019 Australian Community Sector Survey, ACOSS, 2020.

[38] Federal Minister for Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business, ‘Fast tracking the upskilling of Australian workers on Covid-19 safety’, Media release, 4 May 2020.

[39] Future Social Service Institute, Higher Apprenticeships Pilot Project, <https://www.futuresocial.org/higher-apprenticeships-pilot-project/>, accessed 31 May 2020.

[40] Importantly, community service organisations partnered with the government to build, design and implement this project, ensuring it had ‘buy-in’ from the sector and that is was fit-for-purpose. For example, Stage 1 of the Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence project was led by DHHS on behalf of Family Safety Victoria (FSV), in partnerships with VCOSS, Domestic Violence Victoria, Domestic Violence Resource Centre and the Future Social Services Institute. VCOSS invited Expressions of Interest for community service organisations on behalf of DHHS and FSV in Stage 2 of the project.

[41] Family Safety Victoria, Building from strength: 10 year industry plan for family violence prevention response, Government of Victoria, 2017.

[42] VCOSS, Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence Work Project, <https://vcoss.org.au/sector-hub/key-projects/enhanced-pathways-to-family-violence-work-project/>, accessed 24 May 2020.

[43] VCOSS, Expressions of Interest for prospective participating organisations: ‘Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence Work’ – Stage 2, <https://vcoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/FINAL-WEBSITE-UPLOAD-EPFV-stage-2-EOI-INFO-PACK.pdf>, accessed 24 May 2020, p.6.