The Victorian Council of Social Service (VCOSS) is the peak body for social and community services in Victoria. VCOSS supports the community services industry, represents the interests of Victorians facing poverty and disadvantage in policy debates, and advocates to develop a sustainable, fair and equitable society.

VCOSS welcomes the opportunity to provide a submission to the Inquiry into economic equity for Victorian women.

Since November 2014, the Victorian Government has demonstrated a strong commitment to advancing gender equality. This is reflected in Safe and Strong: A Victorian gender equality strategy, the Gender Equality Act 2020 and the establishment of the Gender Equality Commission, alongside broader reforms and significant investment in tackling family violence.

These are landmark reforms that will effect generational change. The Victorian Government’s Inquiry into economic equity for women can build on these strong foundations by identifying – and recommending to government – solutions to problems such as unequal pay and workplace barriers to women’s success.

There has never been a more important time to address these issues. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated existing social and economic fault lines and given rise to new forms of disadvantage.

It has had a regressive effect on gender equality.

In Victoria (and, indeed, globally), women have been over-represented in the sectors hardest hit by COVID-19. Gender Equity Victoria’s analysis found that, in the first year of the pandemic, the payroll impact on women was greater than men across many industries. Gender Equity Victoria also reported that the majority of casual workers unable to access Jobkeeper were women, and that women depleted their superannuation at a higher rate than men when withdrawing emergency COVID-19 funds.[1]

Additionally, COVID-19 has increased the burden of unpaid care. Across six lockdowns in Victoria, responsibility for childcare and supervising children’s home learning has disproportionately fallen on women.

Victorian women have also disproportionately carried care responsibility for other family members, such as aged, disabled or sick parents who are not able to draw on formal supports because of health risks, fear or access barriers.

Many Victorian women are juggling paid work commitments around these unpaid care responsibilities.

Given the short consultation timeframes for this inquiry, VCOSS has primarily focused this submission on addressing economic equity in the community services industry.

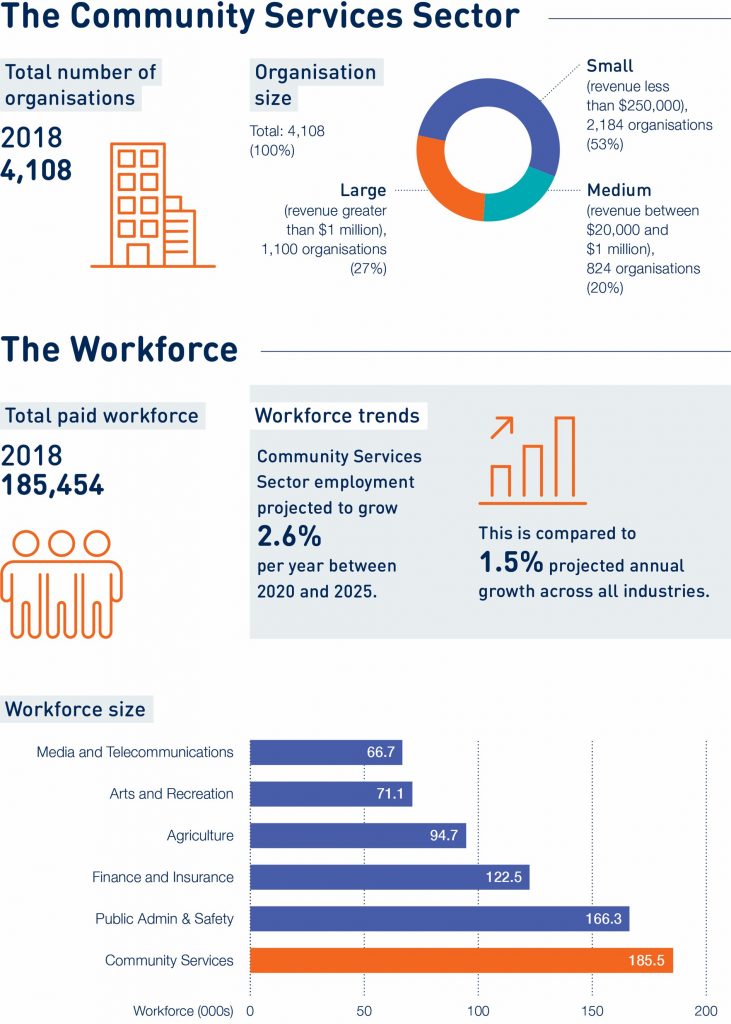

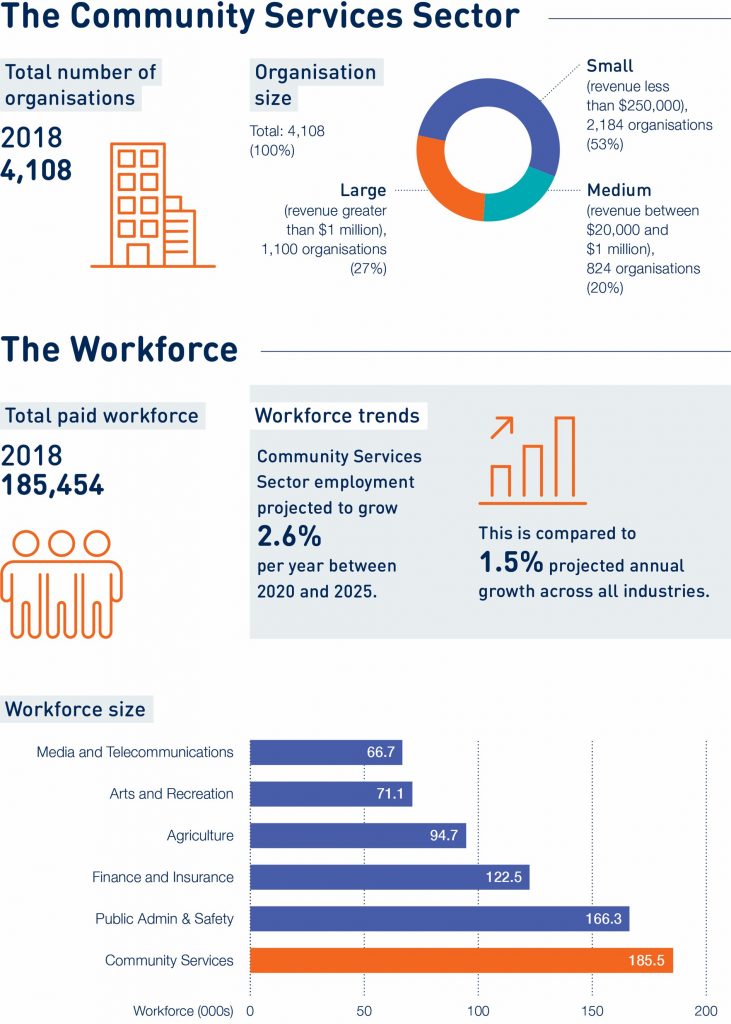

The community services industry is the state’s largest industry based on employment and third-largest based on contribution to GSP.[2] It is highly feminised industry. Women account for 83.5% of the sector’s workforce.

Workers in the sector experience lower pay and conditions in comparison to other industries. Improving pay and conditions for this workforce is essential if we are to reduce economic inequity for women in Victoria, redress systemic undervaluation of the sector, and attract and retain workers to meet growing demand for services.

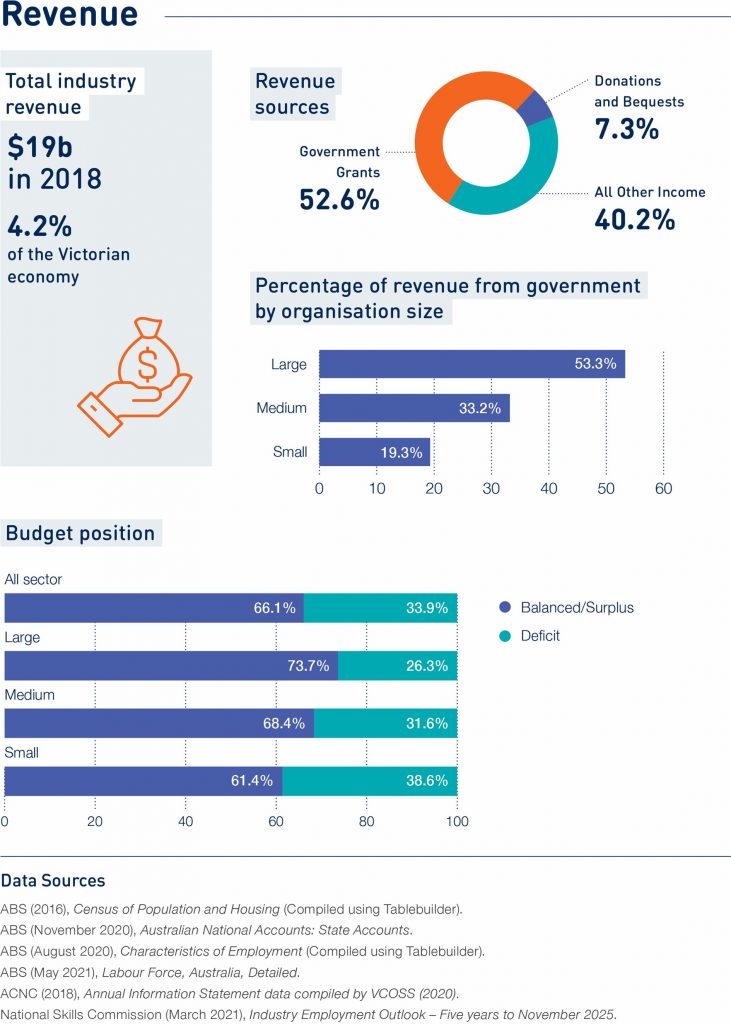

The Victorian Government has a number of levers at its disposal to effect transformational change for workers in this sector. Government funding accounts for over 52% of community service organisations’ incomes, and has a direct impact on wages, conditions and the length of employment contracts. Making changes to the way this funding is indexed – for example, introducing a fair, transparent formula that accounts for changes to key cost drivers – will have a positive flow-on effect for the economic security of workers in this highly-feminised sector. It is just one example of how the Victorian Government can improve equity for Victorian women in work.

This submission identifies a range of other opportunities for government to promote greater job security, create more pathways into work, support access to promotional opportunities for women, leverage our kindergartens, education and training sector, and strategically use the social procurement framework to advance gender equity.

The Victorian Government can also actively advocate to the Commonwealth Government to improve the childcare subsidy and reform parental leave – these two drivers would significantly boost women’s workforce participation and deliver significant economic gains.

VCOSS notes the strong leadership of the Victorian Government at National Cabinet. There is an opportunity for Victoria to work with the Commonwealth Government to effect progressive policy reform for women.

VCOSS has included as appendices to this submission, two flagship reports that focus on workforce challenges and opportunity in the sector. These are:

Additionally, VCOSS has recently produced a Working for Victoria Insights Paper for the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (DJPR), documenting worker and employer perspectives on community sector employment, including secure work, fair pay and related matters. This paper is not yet published, however, VCOSS would be pleased to share it with the Inquiry upon request and with the permission of DJPR.

Promote job security in the community services sector

Progress shared, strategic industry and workforce development priorities identified in the 10-Year Community Services Industry Plan

Continue to fund job creation in the community services sector

Better support for younger workers

Build a diverse community services workforce

Strengthen Victoria’s early childhood education and care, education and training systems

Support access to promotional opportunities in the community services sector

Improve access to affordable education and care to support women’s workforce participation

Advocate for reforms to Australia’s industrial relations system

Advocate to the Commonwealth Government to:

Leverage social procurement

The Victorian community services sector,[3] a component of the broader Health Care and Social Assistance industry, employs approximately 185,454 people.

Employment in the Victorian community services sector is highly gendered, with women accounting for 83.5% of this sector’s workforce. In comparison, women account for 49.6% of the Victorian workforce.

The Victorian community service sector predominantly employs part time workers, accounting for 42% of the workforce. It is also highly casualised, with casuals accounting for 25% of the sector’s workforce. In comparison, casuals account for 18.8% of the Victorian workforce.

Of the 46,000 casual employees in the Victorian community services sector, around 70% are women.

Further data is provided on pages 11 – 13 of this submission. Case studies on pages 14 and 15 bring to life the impacts of insecure, low paid work on workers in family violence and early childhood education and care, and the broader workforce implications. These case studies are illustrative of the experience of workers across the community services sector.

The 2019 Victorian Census of Workforces that Intersect with Family Violence (the 2019 Census)[4] was committed to in the Building from Strength: 10-year Industry Plan for Family Violence Prevention and Response (Building from Strength).

Family violence staff love their work; they just have too much of it

Results from the 2019 Census show that family violence staff, particularly those from the specialist family violence and primary prevention workforces, are highly motivated and committed to working in a family violence response or primary prevention of family violence role. Overwhelmingly, workers love the work they do, have high confidence levels in terms of training and experience, and are satisfied in their current role. They are also buoyed by a strong belief that their work is making a difference.

However, the actual amount of work they are being asked to do is negatively impacting their health and wellbeing, and a significant portion of the workforce plan to leave their role within the next 12 months.

Reasons include:

When asked about changes that could be made respondents indicated:

It is crucial to consider and address these workforce challenges in coming years to ensure that services can meet ongoing demand, maintain sustainability and ensure staff health and wellbeing.

The early childhood education and care workforce is overwhelmingly female.[5] It is experiencing significant strain and exhaustion from a culmination of pre-existing issues that have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like other parts of the community sector, the early childhood education and care workforce has long-experienced issues associated with poor mental health, exhaustion and burnout.

Long-standing issues that need to be addressed include:

The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified these issues. Recent surveys indicate significant parts of the workforce plan on leaving the sector within the next three to five years[6], mirroring workforce data from the Family Violence Census.

Community-based early childhood education and care workforce survey

Early Learning Association Australia, Community Child Care Association and Community Early Learning Australia recently surveyed 360 members to better understand the drivers of staff shortages.

Respondents were kindergarten providers and long day care centres offering kindergarten programs. The survey found staff turnover had increased or greatly increased for 50 per cent of respondents since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

More than half of all respondents indicated the following factors in contributing to staff turnover and shortages:

Over half of survey respondents use above award pay to attract or retain staff.

Services report that staff are also leaving the sector or retiring early due to:

In the kindergarten space, the recently approved Victorian Early Childhood Teachers and Educators Agreement (VECTEA) brings significantly improved pay and conditions for early childhood staff in Victorian kindergartens. The benefits are yet to be felt as implementation is just beginning, but improved conditions will likely improve wellbeing outcomes as a result. The VECTEA is a significant win for the sector, however, there is still work to be done, and it does not cover all staff who work in Commonwealth funded services.

The community sector, like many other industries, continues to face new challenges and ongoing disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Demand is high, and services have been required to adapt established service models at pace. The sector has successfully maintained continuity of support to Victorians requiring social assistance and support through adoption of telehealth and other innovative forms of remote delivery, alongside extensive changes to on-site provision (for example, services such as crisis accommodation).

Research conducted by VCOSS and the Future Social Services Institute into the community sector’s response to the first six months of the pandemic highlighted the agility of the sector. The Stories into Evidence[7] project found services were often running ahead of government in terms of anticipating issues and enacting change, for example, the identification of high-risk workplaces and creation of worker ‘bubbles’/COVID-safe rostering where services could only be delivered face-to-face.

However, 18 months into the pandemic, the cracks are showing. The costs of implementing public health measures continue to be significant and largely unsupported. They coincide with a decimation of fundraising and donation income, and are compounded by other cost pressures, such as increases in the minimum wage, the superannuation guarantee payment and new costs associated with the introduction of the Portable Long Service Leave Scheme.

Services face major sustainability challenges.

Through the Stories into Evidence research, VCOSS heard that many community sector organisations were barely coping with demand pressures prior to the pandemic. During the first six months of COVID-19, services were simultaneously working to maintain continuity of support to existing clients, deal with pent-up demand, and respond to new and emerging needs, including increased demand for family violence, mental health and alcohol and other drug services and an influx of clients who have not traditionally needed to access social support.

Whilst COVID-19’s trajectory remains unknown, it is clear that a sustainable community services sector will be the cornerstone of social and economic recovery.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Victorian Government established the $500 million Working for Victoria Fund to create employment opportunities for people who had lost work due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This important initiative created over 10,000 jobs across essential industries, including more than 1,100 in the community services sector across 54 organisations.

The Working for Victoria Fund helped meet the immediate needs of organisations to respond to a surge in demand for critical services in areas such as family violence, alcohol and other drugs and mental health.[8] The projects funded enabled organisations to build their capacity, reach new cohorts of the community, and created opportunities to help build a pipeline of new workers into the sector.

VCOSS was commissioned by the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions to produce an Insights Paper on the Working for Victoria Fund, for the purpose of informing the Victorian Government’s future job creation initiatives.

The Insights Paper is noted here as the findings are highly relevant to the Inquiry’s deliberations, as are the recommendations, which identify ways to:

“People said they have been working in the sector for 10 years but never had a permanent contract. This makes me question if this is a sector I would like to continue working if that is the case.”

“I could be working in a government job and have more job security and better pay. I have a conflict between job security or doing a job I am more passionate about.”

Short-term contracts constrain socio-economic mobility – for example, without a stable income, people are prevented from getting a home loan. The types of contracts in the community sector were of particular concern to staff in client-facing roles.

“More permanent contracts would be great – we need to reward our works to reflect the amount of effort [that] is going in. People cannot get home loans on six months contracts. Social workers, community workers, youth workers are not respected as highly as other workers. There is a need to include job security to keep really good workers in that line of work.”

Workers also noted that short-term funding in the sector impacts service delivery and the ability to meet the needs of the community.

The undervaluation of the community services sector is well documented.[9] For many years, Victoria’s community services sector has experienced underfunding through low rates of indexation and short-term funding contracts.[10]

The broader sector also experiences relatively lower pay than other industries. Average weekly earnings for the health care and social assistance sector is around $1108, below other industries at around $1207.[11] A community services sector worker earns, on average, $876 per week. This is significantly lower than other industries, for example the construction sector, where a worker earns, on average, $1,466 per week.

RMIT University’s Sara Charlesworth, Professor of Work, Gender and Regulation, in her work on the aged care workforce, has noted:

“One of the key factors that has contributed to the current wages and conditions for the aged care workforce is the gendered nature of the work.

Gender and gender (in)equality sit at the heart of the poor wages and conditions for frontline aged care workers. The workers who undertake this work are overwhelmingly female and the nature of work they perform is highly gendered, historically viewed as quintessentially ‘women’s work’”[12]

The same could be said about other workers – for example in the childcare sector, which is overwhelmingly female and has generally experienced lower wages and conditions than other industries.

Investment in social infrastructure and the care economy creates more jobs than construction

Social infrastructure refers to “the human and social capital that is produced and maintained by caring services, health and education.”[13] Investing in social infrastructure provides similar public good benefits to investing in physical infrastructure (for example, new houses, roads and bridges).[14]

However, as De Henau and Himmelweit note:

“Public spending on social infrastructure is usually seen as a cost rather than an investment, and not considered for investment-led Keynesian stimulus policies, despite having long-term economic and social benefits.”

Significantly, De Henau and Himmelweit’s research across seven OECD countries (including Australia) shows that:

“[i]nvestment in care generates more total employment, including indirect and induced employment, than investment in construction, especially for women, and almost as much employment for men.”

Investing in social infrastructure not only supports job creation, but also has benefits for gender equality.[15]

For every additional 1% of GDP spent on care industries, this would result in twice the number of jobs being created than equivalent investment in construction in Australia.[16]

This research highlights the important role that Victorian Government investment in the community services sector can have in driving job creation for the State’s economy, and the gender equality effects of such investment.

In Victoria, the number of people employed in health care and social assistance almost tripled between the mid-1990s and 2021. Ongoing demand generated by the NDIS, increased demand for childcare and Australia’s ageing population, as well as the industry’s relative resilience to the impacts of COVID-19, suggest strong continued employment growth is likely.

In the next four years to 2025 it is estimated that Victoria will add around 58,000 jobs in the health care and social assistance industry – a 12.3 per cent increase compared to state-wide employment growth of 8.3 per cent. Employment growth rates in the distinctive community service (non-medical) subsectors of the health care and social assistance industry match those of the broader industry.

Employers require targeted government support, for example, through funding more community services industry traineeships and exploring opportunities to earn and learn. However, for these to be successful they need to be co-designed with the sector to ensure they are responsive to employers’ needs. To build employer confidence and buy-in, and maximise impact, they should also apply insights from past projects. Furthermore, they should be complemented by targeted policy measures that address key sustainability challenges that constrain the sector’s ability to create secure jobs.

To support the Victorian Government’s Jobs Plan target to create 200,000 jobs by 2022 (and a total of 400,000 jobs by 2025), the Victorian Government needs to:

The urgent need for fairer indexation

Government funding for community service organisations has been indexed at about two per cent per annum over the past nine years. This rate of indexation has never been sufficient. However, the funding gap has now become a chasm as services face a raft of significant new costs. This year, the Fair Work Commission raised the minimum wage by 2.5 per cent and the superannuation guarantee increased by 0.5% as of 1 July 2021. Since 1 July 2019, a majority of community service organisations have also had to fund the 1.65% portable long service leave levy.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, organisations have also faced increasing cost pressures with lower levels of income coming in from fundraising, increased demand for services, ongoing COVID-19 outlays such as additional cleaning and personal protective equipment, and loss of the volunteer workforce.

With the cumulative impact of both under-funding and short-term funding arrangements, set against a backdrop of exponential growth in community demand for social assistance, community service organisations are under increasing levels of strain.

Underfunding organisations leads to reduced support for vulnerable community members. This ends up costing government more, as the window for early intervention diminishes and the system is oriented to expensive crisis responses.

Unless there is fair indexation that enables the community services sector to meet the true costs of delivering essential services, organisations across the state will be forced to stand down workers and slash services. These job losses will disproportionately affect Victorian women, as the community services workforce is female dominated. It will also impact the sector’s capacity to operate COVID safely.

Over the past 18 months, community service organisations have stepped-up to support Victoria’s response to COVID-19; providing material aid to those doing it tough as well as community health services, family violence response and other critical programs to keep Victorians safe at home and work.

To continue this vital work and ensure that Victorian’s receive the services they need, funding must increase with the true cost of delivering services. A permanent indexation formula, that is fair and transparent, is needed to ensure community service organisations are sustainable and effective into the future.

VCOSS welcomes the Victorian Government’s recent establishment of a working group to progress the development of an indexation formula.

Insecure work driven by short-term funding agreements

Across the community services sector, workers are often employed in insecure work arrangements including casual or fixed term employment contracts.[17] This is due in part to government funding agreements and short-term project funding.

Short-term funding contracts undermine the community sector’s ability to deliver the best possible outcomes for clients.

As the Productivity Commission recognised in its Human Services report, standard contract lengths in the family and community services sector (typically three years or less) are “too short”.[18]

“Three‑year contracts do not give service providers adequate funding stability. Short‑term contracts can also be detrimental to service users because service providers spend too much time seeking short‑term funding, which is a costly distraction from delivering and improving services.

Short contracts can be an impediment to service providers developing stable relationships with service users, hindering service provision and the achievement of outcomes for users. The lack of certainty inhibits planning, collaboration between service providers, innovation and staff retention.”[19]

The Productivity Commission also recognised the challenges of attracting and retaining staff where there was uncertainty about whether contracts would be renewed.[20]

The Productivity Commission recommended that default contract terms should be increased “to seven years, with enhanced safeguards, to achieve a better balance between funding continuity for service providers and periodic contestability”.[21]

Similarly, a recent June 2021 report prepared by the Social Policy Research Centre at UNSW Sydney recommended to “[i]ncrease standard contract lengths for community sector grants to at least five and preferably seven years for most contracts; and 10 years for service delivery in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.”[22]

Increasing default contract terms to at least five and preferably seven years would promote job security in the sector, enabling organisations to reduce the reliance on fixed term and casual employment.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 10-Year Community Services Industry Plan articulates a vision and set of actions to help grow the Victorian community services sector.

It focuses on ensuring that the sector has a diverse workforce that can meeting growing demand, reflecting the diversity of the communities it serves and delivering services in the places where they are needed.

The workforce must have the knowledge, skills and capabilities to ensure that services are person-centred and high quality, with a focus on safety and accessibility.

The Victorian Government should prioritise key workforce priorities under the Community Services Industry Plan so that the sector can attract more people into the workforce, improve workforce retention and meet growing demand for services.

An industry-wide dataset on the community workforce

To make a real impact on people’s lives, it is vital that we shift from just measuring what is delivered – such as the number of hours of service provided to individuals and families – to a greater focus on what is achieved; for example, in relation to health, safety or education outcomes at an individual, service or population level.[23]

Although a lot of data is already being collected, much of this measures outputs, not outcomes, and is not comparable across time or funding streams as reporting requirements differ for each program. Governments and funding bodies request a lot of data, but often do not provide adequate data back to organisations.[24]

The United Kingdom’s Adult Social Care (ASC) Workforce Data Set is a leading example of an online workforce data collection service, providing important information that helps support workforce planning for the adult social care sector in England.[25] It includes information on over 20,000 care providing locations and 750,000 workers, replacing the National Minimum Data Set for Social Care (NMDS-SC) in August 2019.[26]

Modelled on the United Kingdom’s Adult Social Care (ASC) Workforce Data Set, the Victorian Government needs to develop a robust, accessible industry-wide dataset on the community workforce, comparable across sub-sectors and tracked over time to support the growth of the sector.

Investing in a regional workforce development strategy

Prior to COVID-19, the community services sector was experiencing significant levels of demand for services and workforce shortages, particularly in regional areas.

A number of organisations commented on the challenges they experienced in recruiting local workers to regional positions. They noted that, despite these roles having a high number of applicants, the people applying did not have the requisite skills or experience.

The Victorian Government needs to invest in the development of a regional workforce strategy for the community services sector, to help increase the pipeline of workers and ensure that services can be delivered to people locally.

Supporting people with lived experience to become community services industry employees

The CSIP notes the important role played by peer workforce and peer support.[27] People with lived experience can bring greater empathy and understanding to services, and service users often reflect on the benefits of having this additional support.[28] This is also a key finding of the recent Royal Commission into Mental Health.

VCOSS members have reflected on the important role that people with lived experience can play as community services industry employees, particularly in hiring people from culturally and linguistically and diverse communities, or with lived experience of volunteering. These workers play an important role in connecting with community members, and their lived experience enables them to better fulfil their role.

Developing a peer workforce should be prioritised, and people with lived experience engaged as both employees and volunteers in community service organisations across all levels, including reception staff, in personal support, as case managers and board members.[29] Strategies are needed to encourage people with lived experience to become community services industry employees and to support them in their roles.

Streamline and support paid internships and placements of students into the industry

Supporting student placements in the community services sector helps create a pipeline of new workers into the sector by providing students with practical on-the-job training.

There is immense value for organisations in hosting and employing university students as they can shape their development, leverage off their university studies and support a pipeline of workers into their organisation.

For example, in VCOSS’s Working for Victoria consultations, young workers expressed their desire to ‘get a foot in the door’ and commented that student placements focusing on developing key skills like casework would help support their career progression.

Many community organisations would like to take on students and/or interns but do not have the resources for placement administration, student supervision or training.

Programs such as ‘Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence Work’, funded by Family Safety Victoria, help participating organisations to build that capability. Investment in these types of programs should be sustained, scaled and adapted to other parts of the sector.

The Victorian Government could address unique challenges faced by small and mid-size employers by examining the feasibility of a centralised support and supervision model with VCOSS and dual sector TAFE/university partners.

The Victorian Government could also help support the uptake of paid student internships in the sector, which would provide a greater number of opportunities for students and new graduates to develop skills, gain experience, and improve their knowledge of the sector.

These short-term opportunities (three to six months) would enable people to upskill and build their professional networks.

Ensuring they are paid positions reflects good practice and helps reduce barriers for people from disadvantaged backgrounds to participate in these opportunities and gain valuable experience.

Make the community services sector a priority industry

The Victorian Government plays a central role in funding job creation in the community services sector. This is reflected not only through the 1,100 roles created through the Working for Victoria Fund, but also in the fact that it provides more than 50% of community sector funding, supporting the delivery of essential social assistance and support to Victorians.

In order to give substance to ‘community services as a priority industry’, the Victorian Government’s DJPR should consider quarantining a proportion of the funds for the community sector in relevant industry programs. For example, government quarantined a proportion of funds ($50 million) for agricultural and food production industries in regional Victoria as part of Working for Victoria. A similar commitment made to the community sector would recognise the sector’s significant economic contribution and capacity for job creation.

Increase the rates of subsidy under the Jobs Victoria Fund

The Victorian Government is providing $250 million in wage subsidies to assist Victorian businesses and organisations to employ at least 10,000 people who are looking for work through its Jobs Victoria Fund.[30] The Jobs Victoria Fund is the successor to the Working for Victoria Fund.

Organisations were very supportive of the Working for Victoria Fund and were keen to see government continue to invest in job creation, particularly in the community services sector.

Whilst the new Jobs Victoria Fund has been welcomed by organisations, many noted that the current subsidy levels of $10,000 or $20,000 are insufficient to support the sector to take on new employees or continue employing Working for Victoria staff. Higher level of subsidies are needed to support job creation and meet increased demand for community services.

While organisations would like to see a 100 per cent wage subsidy, they recognise that government is unlikely to provide this level of subsidy in the future. However, increasing the Jobs Victoria Fund wage subsidy levels from up to $20,000 to up to $50,000 would engage more community sector employers. At this level of increased subsidy, more community service organisations are likely access the Fund to take on new workers and help grow the pipeline of workers into the sector.

Ensuring that young workers can access employment opportunities and get their ‘foot in the door’ is essential to building economic security and providing the foundations of a good life.

Youth unemployment and underemployment have been persistent policy challenges, even in good economic times. This has intensified during COVID-19, with almost 80,000 more young people out of work.[31]

The Brotherhood of St Laurence Youth Unemployment Monitor found “Young women suffered higher initial job losses, with the sudden closures in largely female-dominated industries such as hospitality, accommodation and retail.”[32] While some jobs have been recovered, the Youth Affairs Council of Victoria has observed that “History shows that youth employment will be the last to recover from this economic crisis.”[33]

In the community services industry, which was relatively more resilient to job losses than other female-dominated industries, impacts for young women workers included disrupted pathways to first jobs (for example, because it was more difficult to complete student placement hours) and reduced participation because of unpaid care responsibilities (for example, supporting young siblings with home learning).

Another dimension of the unpaid care issue (unrelated to COVID-19) is that young women who choose to have children will often take time out of the paid workforce for parental leave, and often return to work part-time in order to balance competing responsibilities.

Evidence shows that women on average have lower superannuation balances as a result of taking time out of the workforce and working part-time following parental leave. Women often are the secondary income earners due to the need to care for children and other family members.

Later sections of this submission identify opportunities to strengthen Australia’s federal parental scheme.

The analysis provided over the page focuses on how to best support younger workers into employment, and is drawn from the insights VCOSS obtained through the Working for Victoria project and other projects such as the VCOSS Community Traineeship Pilot Program (CTPP).

VCOSS’s experience is that young people may need extra support to navigate barriers and retain their employment, as new employees in the community services sector.

Barriers to employment (and training) may include those directly related to work (such as developing a resume, preparing for interviewing, developing work-readiness skills, purchasing appropriate clothing, paying for a computer, or accessing transport), as well as other life challenges such as mental ill-health, homelessness and parenting.

Supported traineeship programs like VCOSS Community Traineeship Pilot Program (CTPP) (funded by Jobs Victoria – through the Victorian Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (DJPR)) have shown the value and importance of young people who are newly employed in the community services sector having access to a support worker for the first 12 months of employment. This is in addition to access to financial resources, which may be used for things like the purchase of computers, paying for transport or paying for counselling services.

Support workers in the CTPP have been able to:

Without this assistance some young people may resign or disengage from work, training and the program.

It is particularly important that young people can connect to their support network within the first month of employment.

Support workers also work with host employers to ensure that young people are supported in the workplace and to address any barriers to engagement; for example, if the young person would benefit from part-time hours rather than full-time. The support worker role is crucial in that it supports and enables effective communication between all stakeholders, ensuring the young person remains at the centre.

Through these supports, young people have shown a significantly higher rate of formal training completion than those in traditional traineeship programs (average of around 70% compared to approximately 57%), and many have also gone onto further employment post-traineeship, with their host employer. Over the course of the first year of employment, the young people have generally indicated that they feel more confident as workers and more resilient to manage change, and have an enhanced identity as a community services worker.

To set new workers up for success, this also requires good orientation and supervision policies as part of structured support and the resources to deliver on that.

Through the Family Safety Victoria workforce development program ‘Enhanced Pathways to Family Violence Work’, which was project managed by VCOSS in its pilot phase in 2018-19, VCOSS and Domestic Violence Victoria/Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria identified that – in order to set new workers up for success – they need a clear statement of their individual role, responsibilities and objectives; an understanding of internal decision making and accountability processes; an understanding of how their work contributes to attainment of organisational vision and goals; and an understanding of how their work contributes to the implementation of organisational strategic and operational plans.

Additionally, new workers and supervisors need to have access to regular supervision sessions; understand the expectations of supervision; and have access to debriefing, as required. New workers also need to receive regular verbal and written feedback on their progress in meeting their individual objectives; be included in team meetings; feel welcomed and a part of the team/organisation; and have any special needs attended to in the workplace. This is resource contingent.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Through the Working for Victoria project, VCOSS partnered with the Ethnic Communities Council of Victoria (ECCV) to deliver a workshop involving women over 45 years who shared their experiences of being employed with community service organisations through the Working for Victoria Fund.

Most of the participants reported significant difficulties in obtaining secure employment in Australia. Many had worked in short-term, casual or gig roles and had been unable to secure permanent employment (particularly in the industries they were qualified for or had significant international work experience).

Many of the women over 45 years reflected on the difficulties balancing their career and family responsibilities and discussed the challenges of caring for young children and finding family-friendly employment.

Some of the common barriers identified by participants to finding employment in Australia included:

Some workers also experienced additional intersectional challenges based on their sex, age and disability. Many of the women over 45 years reflected on the difficulties balancing their career and family responsibilities and discussed the challenges of caring for young children and finding family-friendly employment.

The majority of workshop participants had tertiary qualifications. Many participants had overseas qualifications but found they were not recognised by Australian employers. This was particularly challenging for women over 45, who told us that at their life stage it was unrealistic to begin studying again.

The Victorian Government’s Recruit Smarter report found that jobseekers from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds experience a range of barriers to finding work, including unconscious bias.[34]

As a result, many jobseekers from diverse backgrounds experience higher levels of underemployment and unemployment.[35]

Unconscious bias and discrimination in hiring practices was noted as a barrier by a number of Working for Victoria employees.[36] Other barriers also discussed include overseas qualifications, skills and experience not being recognised, employer demands for local experience, lack of networks and lack of English language skills.

Identifying ways in which these barriers can be overcome is crucial to helping support more people from diverse backgrounds into employment. Not only is diversity important for the workforce, it is also good for the economy and the community. Research shows that diverse workplaces are “more efficient, better at problem solving, more creative and more resilient in economic and financial downturns.”[37]

The Victorian Government should revisit its Recruit Smarter report to identify ways in which it can help reduce unconscious bias. This should include, for example, promoting its guidelines on best practice for inclusive recruitment to Victorian businesses and organisations.

Victoria’s Overseas Qualifications Unit (OQU) offers free and confidential assessment services to have people’s qualifications recognised in Australia. Ensuring that people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities are aware of the OQU and that organisations have good linkages into different communities will help promote the service and support more people to have their overseas qualifications recognised.

The Victorian Government’s $169.6 million dollar investment in free kindergarten for 2021 as part of the government’s response to COVID-19 was intended to:

For many working families, the number of hours and days currently provided by kindergartens in Victoria makes it difficult to utilise this service and meet work commitments.

Whilst each service is different, kindergarten programs often run across three days a week for 5 hours a day, or across 2 days a week at 7.5 hours. In some cases, services may provide 2 x 5.5 hour sessions and 1 x 4 hour session.

Whilst many Long Day Care services provide embedded kindergarten programs, the Victorian Government could consider undertaking a scoping exercise to examine ways of utilising existing infrastructure, the trust early learning providers already hold within their communities, and explore ways of extending care for children before and after care to boost workforce participation.

For example, small, stand-alone kindergartens who offer high-quality early learning but may be facing sustainability constraints could facilitate the delivery of occasional care before and after a kindergarten program. This would make better use of existing infrastructure, support provider viability, and give greater options for female workforce participation in areas of need.

RECOMMENDATION

The Free TAFE initiative has removed the major cost barrier to training in priority industries – many of which are in the community services with female-dominated workforces.

The Victorian Government can increase access to Free TAFE for women and boost completion rates by:

Peripheral costs to education such as the cost of textbooks, a digital device or other course materials and equipment, pay for childcare or transport, or pay for a Working with Children Check can create barriers to engaging in education.

Government can extend existing scholarships available to parts of female-dominated industries for Bachelor level students[39] by investing in an equivalent scholarship program to remove cost barriers and support women to access Free TAFE.

In addition, low VET completion rates[40] indicate more could be done to support retention and completion. TAFEs already provide a range of student supports but some students have complex needs that exceed what is currently provided. With additional funding, TAFEs could increase access to personalised supports to boost student completion – such as mentoring, counselling, literacy and numeracy support, assessment adjustments and warm referrals to specialist supports (such as family violence or housing and homelessness agencies).[41]

RECOMMENDATION

The Victorian Government can increase access to affordable training for women by removing ‘two-course’ rule restrictions and ‘upskilling’ rule restrictions.

The government-commissioned Macklin Report identified these rules were complex and hard to navigate for learners and providers alike, and, “are not fit for a future in which all Victorians need to engage in lifelong learning”, don’t support career changes and are not responsive to economic shifts.[42]

These rules create specific barriers for women. For example, there are many reasons why a student may not complete a course, including experiences of homelessness, mental ill health, family violence, or changed caring responsibilities. These can disproportionately impact women because women are more likely to:

These rules also create barriers for women in re-skilling, upskilling or changing careers after returning to work after having children.

While government has invested in funding and initiatives to increase access to training for women and others disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic,[45] the Victorian Government should implement the full suite of recommendations made in the Macklin Report to ease eligibility restrictions. [46]

RECOMMENDATION

In the female-dominated community services sector, women are under-represented in senior leadership. Around 87% of the community services workforce identifies as female (compared to 47% of the total workforce). The sector is also strongly characterised by part time employment (64% are employed PT, compared to 32% of the total workforce).[47] However, only 60% of senior leadership positions are occupied by women [48], and a review of job ads found only 25% are offered as part time.

Part time or co leadership can expand the participation of women in the community services sector. However, there are gaps in knowledge about this form of leadership; no resources to build organisational or individual capacity; and no models of good practice for the sector.

A further constraint is persistent negative stereotypes about part time work. Across all industries, women are seeking greater flexibility in working arrangements, including part time work.[49] However, there is a perception that uptake of flexible work demonstrates a lack of commitment to the job. Some research suggests that women who access flexible arrangements are more likely to be viewed as unsuitable for management roles and less likely to be promoted.[50] There is evidence that colleagues of those who work part time or flexibly view this negatively.[51]

In the community services industry, these factors limit women’s ability to take on leadership roles and means the sector is failing to leverage available talent.

This is concerning given:

This area of women’s leadership and development – part-time and co leadership – is largely unexplored in Australia. The Victorian Government can help advance this space by supporting VCOSS and Gender Equity Victoria to elicit insights and design and test a model to support more part-time and co leadership positions in the sector.

This project would contribute to improvements in the economic security of Victorian women by:

RECOMMENDATION

Whilst early childhood education and care is an essential service that supports families’ workforce participation, the Commonwealth Government’s current childcare subsidy levels remain unaffordable for around 40% of families[54] and 48% of low-income families.[55]

Whilst the Commonwealth Government has proposed reforms to the childcare subsidy (due to take effect in July 2022), these do not go far enough in addressing concerns around affordability and the effective marginal tax rates that many women experience if they increase their hours at work.

Evidence suggests “that high effective marginal tax rates deter women, especially those with young children, from working more.”[56]

In some cases, women can face:

“high effective marginal tax rates – as much as 95% for those in low-income households – on income from extra days worked. This is because the extra earnings interact with policies including income tax rates, the Medicare levy and losing family benefits, combined with the net cost of child care.”[57]

Analysis by the Grattan Institute regarding the impact of the new childcare policy on workforce participation rates notes that the new policy will lower these “workforce disincentive rates”.

They modelled the current and proposed impacts of the new childcare subsidy scheme:[58]

The Grattan Institute notes that the:

“The mother will now lose 75% on the fourth day and 90% on the fifth day.”

When education and care is unaffordable, children are more likely to miss out on high-quality early learning that sets them up for success in the years before school and women’s employment is constrained.

The Commonwealth should develop a new funding model that recognises the rise in dual income working families and delivers a childcare system that is accessible, affordable and supports family and community needs and choice. A new design should be responsive to:

Delivering a new funding model would provide greater economic stimulus by increasing female workforce participation and have the twin benefit of driving up participation in early childhood education and care. It would also provide government with greater opportunity to support pay and conditions and look at funding levers to improve service quality.

The Victorian Government can help advance this issue through advocacy to the Commonwealth Government.

RECOMMENDATION

Australia’s industrial relations laws have not kept pace with modern society and changing labour market conditions. The industrial relations system assumes a traditional, full-time employer-employee relationship however only approximately 50% of workers fall in this category.

Paid parental leave

Australia’s national parental leave scheme comprises:

Many workers are also able to access additional leave provided by employers through their enterprise agreements, with a number of leading Australian businesses providing up to 26 weeks of flexible paid parental leave.[59]

The Victoria Public Service has also recently negotiated a new agreement with staff for 16 weeks for primary carers and 4 weeks for secondary carers (and additional 12 weeks if they take over the primary responsibility for the care of the Child within first 78 weeks).[60]

While many organisations, government and businesses are removing the distinction between primary and secondary carers from their enterprise bargaining agreements, Australia’s federal parental scheme has not been significantly revised since it was first introduced in 2011.

Take up of Dad and Partner Pay also remains very low.

In line with the Productivity Commission recommendations that parents need 6-12 months in order to support the best outcomes for their children,[61] VCOSS recommends that the Victorian Government advocate to the Commonwealth to introduce at least 26 weeks of paid parental leave under the National Employment Standards.

The Victorian Government can also leverage its Social Procurement Framework to encourage businesses and organisations employers to adopt stronger paid parental leave policies (discussed below).

Fixed term contracts

The use of fixed term contracts not only negatively impact workers, it also undermines organisations’ ability to retain experienced workers and deliver the services that vulnerable and disadvantaged members of the community rely on.

Insecure work arrangements is a key barrier to supporting the growth of the community services sector.

To provide an additional pathway for permanency for employees, the Victorian Government should advocate to the Commonwealth Government to amend the Fair Work Act 2009 to place a cap on the number of consecutive fixed-term contracts at 24 months or two consecutive contracts – whichever comes first.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Advocate to the Commonwealth Government to:

Introduce at least 26 weeks of paid parental leave under the National Employment Standards for each parent.

Amend the Fair Work Act 2009 to place a cap on the number of consecutive fixed-term contracts at 24 months or two consecutive contracts – whichever comes first.

As federal, state and local government departments and agencies are the largest purchaser of goods, services and construction projects in Australia, they have an important role in driving the use of public expenditure to improve social and economic outcomes.[62]

Social procurement refers to organisations using their buying power to generate social value above and beyond the value of the goods, services, or construction being procured.[63]

Victoria’s Social Procurement Framework (Framework) was released in 2018 and was the first whole-of-government commitment to social procurement in Australia.[64] It sets a clear expectation that social procurement is standard practice for the Victorian Government.

“Women’s equality and safety” is one of seven social procurement objectives included in Victoria’s Framework.[65] The two nominated social outcomes for Victorian Government suppliers are adoption of family violence leave; and gender equality suppliers.[66]

Under the model approach for government buyers, suppliers are required to complete a gender equitable business practice self-assessment checklist, and provide a current workforce profile. The key components of the checklist include:

Th Victorian Government should consider adding parental leave to this list, recognising the important role that paid leave plays in supporting primary carers balance their work and caring responsibilities.

While most working women can access the 18-week Commonwealth funded parental leave payment, only 50% of working parents can access employer-funded schemes.[67]

Many organisations, government and businesses are removing the distinction between primary and secondary carers. For example, the VPS has just negotiated a new agreement with staff for 16 weeks for primary carers and 4 weeks for secondary carers (and additional 12 weeks if they take over the primary responsibility for the care of the Child within first 78 weeks).[68]

Leveraging social procurement to encourage more businesses and organisations to increase their paid parental leave payments for primary and secondary carers would help improve gender equality for all Victorian women.

RECOMMENDATIONS

[1] Gender Equity Victoria, Towards a Gender Equal Recovery 2021/22, Submission to the 2021-22 Victorian State Budget, p.6

[2] Based on Gross Value Added – Chain volume measures, Victoria (2019-2020). Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (November 2020), Australian National Accounts: State Accounts

[3] Includes child care services and other social support services (including aged care assistance, disabilities assistance, marriage guidance, welfare counselling and youth welfare services) as well as residential care services (including aged care and respite, hospice, crisis care, mental health, and children’s residential services.

[4] Victorian Government, 2019-20 Census of workforces that intersect with family violence: Summary findings report, https://www.vic.gov.au/summary-findings-report-2019-20-workforce-census

[5] Victorian Skills Commissioner, Sector Snapshot: Victoria’s Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) Sector, December 2020.

[6] Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority, National Children’s Education and Care Workforce Strategy: Public consultation findings May 2021, 2021; United Workers Union, Exhausted, Undervalued and Leaving: The crisis in Early Education, August 2021.

[7] VCOSS and the Future Social Service Institute were commissioned by the Department of Health and Human Services in late June 2020 to gather, test, analyse and interpret critical intelligence from a diverse range of front-line service providers working across a range of service areas including disability, mental health, homelessness, Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs), children and families, family violence, aged care, youth and justice. The Stories Into Evidence report documented the Victorian community services sector’s response to the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, it identified adaptations to service delivery and practice, and emergent changes in service-user demand and community need.

[8] Future Social Services Institute and Victorian Council of Social Service, 2020, Stories into Evidence:

Covid-19 adaptations in the Victorian community services sector, p. 10.

[9] Valuing Australia’s community sector: better contracting for capacity, sustainability and impact, https://www.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ACSS-2021_better-contracting-report.pdf

[10] Government funding accounts for over 52% of community service organisations’ incomes, and has a direct impact on worker’s wages, conditions and the length of their employment contracts.

[11] ABS, Survey of employee earnings and hours, 2018.

[12] Edited Statement of Professor Sara Charlesworth, RMIT University, to the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality & Safety October 2019, Statement made in Response to Questions from the Royal Commission.

[13] Jerome De Henau and Susan Himmelweit, The gendered employment gains of investing in social vs. physical infrastructure: evidence from simulations across seven OECD countries, IKD Working Paper No. 84, April 2020

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] McKell Institute Queensland, Understanding Insecure Work in Australia, https://mckellinstitute.org.au/app/uploads/McKell-Institute-Queensland-Understanding-Insecure-Work-in-Australia-1-2.pdf, p.5.

[18] Productivity Commission, Introducing Competition and Informed User Choice into Human Services: Reforms to Human Services, https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/human-services/reforms/report/human-services-reforms.pdf, p.245

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid, p.246.

[21] Ibid, p.235.

[22] Blaxland, M and Cortis, N (2021) Valuing Australia’s community sector: Better contracting for capacity, sustainability and impact. Sydney: ACOSS.

[23] 10-year Community Services Industry Plan, September 2018, https://vcoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CSIP-Sept-2018-FINAL-single-page-web-version.pdf, p. 22

[24] Ibid.

[25] Skills for Care, Adult social care workforce data, https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/adult-social-care-workforce-data.aspx

[26] Ibid.

[27] 10-year Community Services Industry Plan, September 2018, https://vcoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CSIP-Sept-2018-FINAL-single-page-web-version.pdf, p.18.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Victorian Government, Jobs Victoria, https://jobs.vic.gov.au/about-jobs-victoria/our-programs/jobs-victoria-fund

[31] Youth Affairs Council of Victoria and Young Workers Centre, Youth employment plan needed as 20,000 new graduates enter job market, 23 November 2020

[32] Brotherhood of St Laurence, ‘COVID the greater disrupter. Another blow to youth employment’, Youth Unemployment Monitor, December 2020

[33] Op. cit.

[34] Department of Premier and Cabinet Victoria, Recruit Smarter: Report of Findings, p.3.

[35] Ibid.

[36] See VCOSS, Working for Victoria Insights Paper, July 2021.

[37] Department of Premier and Cabinet Victoria, Recruit Smarter: Report of Findings, p.4.

[38] The Education State, Early Childhood Education Free Kinder Frequently Asked Questions, November 2020.

[39] Department of Education and training, Financial support to study and work in early childhood, <https://www.education.vic.gov.au/childhood/professionals/profdev/Pages/scholarships.aspx>, accessed 12 August 2021.

[40] Public Accounts and Estimates Committee, 2021-22 Budget Estimates – Training and Skills and Higher Education, 21 June 2021, pp. 11-12; National Centre for Vocational Education Research, Australian vocational education and training statistics: VET qualification completion rates 2018, 2020.

[41] Youth Action – Uniting – Mission Australia, Vocational Education and Training in NSW: Report into access and outcomes for young people experiencing disadvantage – Joint report, February 2018.

[42] J Macklin, Future Skills for Victoria, Driving collaboration and innovation in post-secondary education and training, Victorian Government, 2020, p.105.

[43] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Specialist homelessness services annual report, 11 December 2020, <https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/specialist-homelessness-services-annual-report/contents/summary>, accessed 12 August 2021.

[44] Australian Human Rights Commission, Risk of Homelessness in Older Women, 4 April 2019, <https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/age-discrimination/projects/risk-homelessness-older-women>, accessed 12 August 2021.

[45] Victorian Department of Education and Training, Public Accounts and Estimates Hearing – Budget 2021-2022. Minister Tierney presentation, 21 June 2021.

[46] J Macklin, Future Skills for Victoria, Driving collaboration and innovation in post-secondary education and training, Victorian Government, 2020, pp.103-104.

[47] ABS, Welfare workforce – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (aihw.gov.au), 2018.

[48] ACOSS, NFP_Boards_and_Gender_Diversity_2012_final.pdf (acoss.org.au), p.18.

[49] Centre for Ethical Leadership, Ethical Leadership, 2013.

[50] Gloor et al., An inconvenient truth? Interpersonal and career consequences of “maybe baby” expectations – ScienceDirect, 2018

[51] Ibid.

[52] WGEA, Gender Equity Insights series.

[53] Centre for Ethical Leadership, Ethical Leadership, 2013.

[54] K Noble & P Hurley, Counting the cost to families: Assessing childcare affordability in Australia, Mitchell Institute, Victoria University, 2021.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Miranda Stewart, Mothers have little to show for extra days of work under new tax changes, 20 June 2018, https://theconversation.com/mothers-have-little-to-show-for-extra-days-of-work-under-new-tax-changes-98467

[57] Ibid.

[58] The Coalition’s child-care subsidy plan: how it works, and what it means for families and the economy, 3 May 2021, https://theconversation.com/the-coalitions-child-care-subsidy-plan-how-it-works-and-what-it-means-for-families-and-the-economy-160173

[59] For example, see KPMG, KPMG introduces 26 weeks of flexible paid parental leave, 2021, https://www.consultancy.com.au/news/3581/kpmg-introduces-26-weeks-of-flexible-paid-parental-leave#:~:text=Professional%20services%20firm%20KPMG%20has,of%2026%20weeks%20paid%20leave.&text=The%20firm%20has%20also%20extended,cultural%20flexibility%20around%20public%20holidays.

[60] Victorian Public Service Enterprise Agreement 2020, https://www.dtf.vic.gov.au/funds-programs-and-policies/victorian-public-service-enterprise-agreement-2020

[61] Australian Government Productivity Commision, Paid Parental Leave: Support for Parents with Newborn Children No 47, 28 February 2009.

[62] University of Melbourne, Maximising the Potential of Social Procurement, https://government.unimelb.edu.au/research/regulation-and-design/Home/Maximising-the-Potential-of-Social-Procurement

[63] The State of Victoria Victoria’s social procurement framework 2018, accessed 11 October 2018

[64] Victoria’s social procurement framework, 2018, https://www.buyingfor.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-08/Victorias-Social-Procurement-Framework.PDF

[65] The Victorian Government, Detailed guidance for women’s equality and safety, https://www.buyingfor.vic.gov.au/detailed-guidance-womens-equality-and-safety

[66] Ibid.

[67] (Baird et al, 2021).

[68] Victorian Public Service Enterprise Agreement 2020, https://www.dtf.vic.gov.au/funds-programs-and-policies/victorian-public-service-enterprise-agreement-2020

(1/1) ErrorException |

|---|

| in download-attachment.php line 6 |

| at RegisterExceptionHandler->handleError(8, 'Trying to access array offset on value of type bool', '/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/partials/download-attachment.php', 6, array('slug' => 'partials/download-attachment', 'args' => null, 'return' => false, 'wp_query' => object(WP_Query), 'templates' => array('partials/download-attachment.php'), 'template_file' => '/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/partials/download-attachment.php', 'page' => 0, 'year' => 2021, 'monthnum' => 8, 'name' => 'supporting-the-community-services-sector-post-covid-19', 'category_name' => 'uncategorized', 'error' => '', 'm' => '', 'p' => 0, 'post_parent' => '', 'subpost' => '', 'subpost_id' => '', 'attachment' => '', 'attachment_id' => 0, 'pagename' => '', 'page_id' => 0, 'second' => '', 'minute' => '', 'hour' => '', 'day' => 0, 'w' => 0, 'tag' => '', 'cat' => '', 'tag_id' => '', 'author' => '', 'author_name' => '', 'feed' => '', 'tb' => '', 'paged' => 0, 'meta_key' => '', 'meta_value' => '', 'preview' => '', 's' => '', 'sentence' => '', 'title' => '', 'fields' => array(array('file' => false), array('file' => false)), 'menu_order' => '', 'embed' => '', 'category__in' => array(), 'category__not_in' => array(), 'category__and' => array(), 'post__in' => array(), 'post__not_in' => array(), 'post_name__in' => array(), 'tag__in' => array(), 'tag__not_in' => array(), 'tag__and' => array(), 'tag_slug__in' => array(), 'tag_slug__and' => array(), 'post_parent__in' => array(), 'post_parent__not_in' => array(), 'author__in' => array(), 'author__not_in' => array(), 'search_columns' => array(), 'ignore_sticky_posts' => false, 'suppress_filters' => false, 'cache_results' => true, 'update_post_term_cache' => true, 'update_menu_item_cache' => false, 'lazy_load_term_meta' => true, 'update_post_meta_cache' => true, 'post_type' => '', 'posts_per_page' => 30, 'nopaging' => false, 'comments_per_page' => '50', 'no_found_rows' => false, 'order' => 'DESC', 'field' => array('file' => false), 'file' => false))in download-attachment.php line 6 |

| at require('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/partials/download-attachment.php')in Core.php line 74 |

| at Core::get_template_view('partials/download-attachment')in single-post-content.php line 12 |

| at require('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/partials/single-post-content.php')in Core.php line 74 |

| at Core::get_template_view('partials/single-post-content', null, true)in single-post.php line 21 |

| at include('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php')in WordPressControllersServiceProvider.php line 23 |

| at WordPressControllersServiceProvider->handleTemplateInclude('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php')in class-wp-hook.php line 324 |

| at WP_Hook->apply_filters('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php', array('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php'))in plugin.php line 205 |

| at apply_filters('template_include', '/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php')in template-loader.php line 104 |

| at require_once('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-includes/template-loader.php')in wp-blog-header.php line 19 |

| at require('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-blog-header.php')in index.php line 17 |