To fix Victoria’s criminal justice system we need to:

A key focus of our work at VCOSS is to advocate for change that will enable Victorians to live a good life.

Good lives are lived in strong, connected communities, where people have a safe and stable place to call home, timely access to health care and social support, the opportunity to participate in education, training and employment, and have agency over their own lives.

Strong communities lead to safe communities. If people experience social exclusion, inequality and disadvantage, and cannot access the support they need, they are at risk of engaging in antisocial or offending behaviours.

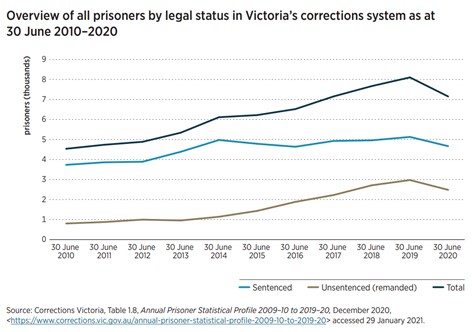

The Victorian Government has instituted many progressive social policy reforms that positively shift the dial for Victorians. However, in the criminal justice space, a range of reforms unnecessarily criminalise or incarcerate people and entrench disadvantage and exclusion. The most notable example is the 2018 bail reforms that have driven an alarming increase in the number of people in prison on unsentenced remand.

The Legal and Social Issues Committee has a track record of contributing to progressive evidence-based policy reform in Victoria. Prison has been found to be an ineffective and expensive way to respond to criminal behaviour or to keep communities safe. This Inquiry provides an opportunity to support transformational change by championing recommendations that address the root causes of offending.

Protect Victorians against poverty

Eliminate disadvantage by shifting to a wellbeing economy and adopting justice reinvestment

Prioritise the critical role of housing in preventing criminalisation and reoffending

Give people the health and social support they need in their communities

Improve access to justice with early legal assistance

Address overrepresentation of women, people with disability, children and young people, First Nations people and victims of crime

Reform the laws that are causing the most harm

Make interactions with the justice system safe, respectful and accessible

Prioritise the health and safety of all Victorians in police practice

Create more problem-solving and diversionary courts

Ensure people leave prison for good

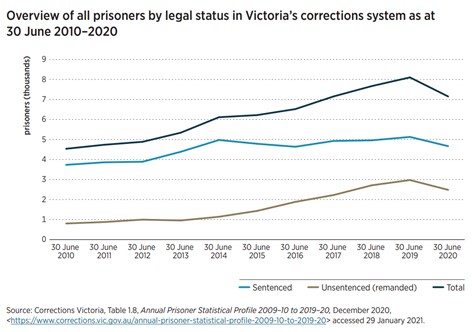

Victoria’s justice system is built around equal principles of deterrence, rehabilitation, punishment, and community safety. However, a law and order, tough on crime rhetoric fuelled by media has seen successive governments implement criminal justice system reforms that rely on punitive responses to antisocial behaviours and offending. The most stark example of this is our ever-increasing incarceration rate (see table below).

The overreliance on punishment is a narrow conception of justice and as the Victorian Ombudsman stated in 2015, prison is an ineffective and expensive way to respond to criminal behaviour or to keep communities safe.[1]

Instead, social justice principles should be used to guide criminal justice system reform. The concept of social justice acknowledges that individuals are embedded in, and shaped by, their social environment. If social inequality and exclusion drive people to engage in antisocial or offending behaviours, then a collective, whole-of-government and community response is required to prevent crime, and to intervene early to prevent further harm.

Recommendations

Social inequality and exclusion, in the form of social, economic or intergenerational disadvantage, limited education and employment opportunities and poor health and wellbeing, is a risk factor for antisocial and offending behaviours. Eliminating social exclusion requires intervention at the population, community and neighbourhood levels.

Poverty is the most stark example of social inequality. Thirteen (13) per cent of Victorians currently live in poverty.[2] Poverty exists in every Victorian community, with rates highest in regional and rural Victoria. Poverty stops people living healthy and happy lives. It can lead to isolation, to children disengaging from school, and to poor physical and mental health.

At the population level, having an adequate income is a critical protection against poverty. Our national safety net is currently failing to provide that protection. For example, Victorians reliant on the base rate of the JobSeeker income support payment live well below the poverty line. – For example, a single person without children is $166 per fortnight under the poverty line.

Another critical protection against poverty is secure work. Employment participation contributes to individual and community well-being. Stable paid employment provides people with an income and contributes to their sense of identity and wellbeing. It enables people to put a roof over their head and pay for food, transportation, clothing, energy, childcare, health care, and access to information technology.

Not every Victorian has the security of stable employment. There are high rates of unemployment and underemployment concentrated in some groups, including young people, people who have been early school leavers, Aboriginal people, people with disabilities, people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities, people with enduring health issues (including drug and alcohol or chronic health conditions), and people who have a criminal record.

VCOSS considers that creating pathways to participation for disadvantaged jobseekers is a key element of effective prevention, early intervention and reintegration.

The Victorian Government is already playing an important role through Jobs Victoria. The investment in new non-punitive, place-based supply-side measures – for example, mentors, advocates and counsellors – is already supporting many disadvantaged jobseekers into work, including Victorians who have had justice-system involvement.

Additionally, through the Jobs Victoria Fund, a successor to the Working for Victoria Fund, DJPR is continuing to invest in demand-side measures, through the provision of targeted, tiered wage subsidies to employers (albeit at a significantly lower rate of subsidy than Working for Victoria).

VCOSS urges sustained Victorian Government investment in employment support for disadvantaged jobseekers and initiatives that support the creation of high-quality jobs.

For those in work, the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) is the most prominent lever to strengthen employment protections for all workers. Significant reforms are needed to ensure that all workers in Australia can access the minimum employment rights to ensure that they can not only meet their basic needs but can flourish and fully participate in life.[3]

The pandemic has reinforced that minimum employment entitlements benefit not just individuals, but the whole community. The Victorian Government can advocate that the Commonwealth reform the Fair Work Act 2009 to improve protections for insecure and casual workers and independent contractors.

Recommendations

Victoria can also take steps to eliminate social inequality and exclusion by reorienting the state’s economy to a wellbeing economy. In broad terms, wellbeing economies put the pursuit of key social outcomes – like delivering the basic needs for food, housing, health, safety and a good education – on par with the pursuit of good balance sheets. Governments are required to clearly articulate specific social goals and match them with concrete targets and timelines, then publicly report on progress at set intervals. These are embedded through the delivery of wellbeing budgets.

Justice reinvestment is a proven approach to tackling community and neighbourhood level disadvantage that is highly compatible with wellbeing budgeting. Justice reinvestment involves re-directing resources that would normally be spent on prisons towards local, community-based initiatives that prevent people from engaging in offending behaviours. A justice reinvestment approach uses data to identify need and provides local communities with the resources, time and space to come together and build resilience and cohesion to make the local area safer, smarter and healthier.

The Maranguka Justice Reinvestment Project in Bourke, New South Wales, is one of the most successful examples of justice reinvestment. Historically, the town has had crime rates well above the NSW average, and consistently experiences the highest recorded crime rates in NSW for domestic violence, sexual assault and breach of bail.

An evaluation conducted after five years found that incidences of domestic violence had dropped by about a quarter and reoffending had reduced. A third more young people are finishing high school. Other results include:

The Victorian Government should work with communities to identify areas of need in Victoria where a justice reinvestment pilot would be effective. To help guide this work, and ensure the efficient and equitable use of resources, the Government should establish a justice reinvestment framework. As well as coordinating funding and providing a foundation for strong governance arrangements, the framework would be an enabler for building shared evidence on effective practice.

Recommendations

Safe, stable and affordable housing plays a critical role in preventing contact with the criminal justice system, reducing contact with the criminal justice system and supporting successful reintegration for people following contact with the justice system.

As VCOSS told this Committee in the Inquiry into Homelessness in Victoria:

The Victorian Government’s Big Housing Build is a welcome and much needed investment in social and affordable housing. However, most of the growth in this program is through community housing, which may not be accessible to people who are justice-involved or who have been criminalised.

To ensure that housing is provided for those most in need, VCOSS recommended that the Victorian Government invest in a pipeline of new social housing stock, comprising both public and community housing, under the yet to be finalised Ten Year Strategy for Social and Affordable Housing.

Further, the Victorian Government should consider additional support and resources required for community housing providers to make allocations to people who are justice-involved or who have been criminalised. The Victorian Government can facilitate this by quarantining a portion of future stock for people involved in the justice system and by inviting bids from or incentivising the community housing sector to deliver specialist housing.

All new public and community homes should be designed to prioritise safety (including cultural safety and freedom from violence), and be made accessible, with appropriate space to accommodate children/dependents and/or the provision of necessary supports. For people who have been criminalised, it is necessary for housing and support to be provided separately to ensure that people can exercise choice and control over their own life, without their housing provider having an undue level of influence (for example, VCOSS members note poor outcomes for people they support when Corrections Victoria is both the housing and support provider).

A third of all Victorians rent homes in the private market, including many who would be eligible for public and community housing but who do not have access due to supply constraints. People who are at risk of, or who have experienced, justice involvement face unique challenges in the private market, including unaffordability, poor quality or unsuitable homes, and stigma and discrimination, and may face challenges with meeting their tenancy obligations that place them at risk of eviction.

An ambitious suite of renting law reforms commenced in March this year, which make renting fairer through changes including more secure tenure and protections against evictions. The Victorian Government should work with community to establish a mechanism to monitor implementation of the reforms and consider any additional protections or supports that might be required to ensure people who are justice involved can maintain private rental housing.

Recommendations

Ensure community sector organisations have the capacity to deliver effective early intervention supports and the right supports that respond to people at risk of criminalisation or who have complex needs by:

As the Victorian Ombudsman noted in a 2015 investigation, there is a clear link between disadvantage and justice system involvement.[6]

This investigation, along with a growing body of research in recent years, highlights that people who become justice involved or criminalised often face a range of health and social issues that may not be identified, or, if identified, have not been treated,[7] when they encounter the justice system. For example:

Providing the support people need early in their communities is a critical way to prevent people from becoming involved in the justice system. At a workshop to inform this submission, VCOSS members noted the following features of effective early intervention practice when working with people who have been criminalised or who have complex, co-occurring needs:

However, due to short-term and precarious funding, as well as disruptions arising from critical but sometimes uncoordinated sector reforms, workers and agencies may not have capacity to deliver supports that prioritise these features. As a consequence, people face barriers getting the support they need at the earliest opportunity, and may instead only access support when facing crisis, or critically, never access support before becoming justice-involved. The Victorian Government can effect transformational change by providing fairer funding and longer-term contracts, as well as enhancing the way concurrent, intersecting flagship reforms are implemented. There is an opportunity for enhanced coordination and integration of key reforms.

Noting that many people currently involved in Victoria’s criminal justice system present with mental health and AOD issues, Government must address barriers to accessing community-based mental health and AOD support.

As this Committee noted in the Inquiry into the Use of Cannabis in Victoria, the AOD sector is underfunded and faces significant workforce shortages.[15] Despite the crossover between the AOD and the mental health service systems, the two systems are uncoordinated, which creates issues for services users. VCOSS welcomes the Victorian Government’s commitment to establish a state-wide mental health and AOD service to promote clinical cooperation between the two systems. However, with significant investment already committed to reform the mental health system in line with the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, the Victorian Government will need to undertake robust modelling of AOD service demand, and plan and resource services to address workforce issues that may arise with mental health system reform.

Recommendations

People most vulnerable to legal problems often have fewer skills and resources to deal with them without assistance. Targeted legal assistance, delivered at the right time and the earliest possible opportunity, can help resolve problems that can otherwise escalate, leading to more problems, greater disadvantage and higher costs.

Community justice partnerships put lawyers into places where people can access them easily during their everyday lives, such as community health services, family violence services or schools. People experiencing legal problems are more likely to confide in a GP, a social worker or their teacher than go to a lawyer.

Embedding lawyers in community settings gives people a chance to address their legal needs before they spiral out of control. It means non-legal professionals receiving information from someone can work with lawyers to jointly address that person’s needs.

Community legal centres have experienced a surge in demand since the start of the pandemic, at the same time as courts are experiencing significant backlogs in hearing matters. The Victorian Government should work with the community legal sector to model future demand and fund the sector to meet this demand. Further, per the recommendations of the Access to Justice Review, the Victorian Government should provide ongoing funding for integrated legal and non-legal supports, to address service gaps and silos, and ensure Victorians can access more effective legal help.

recommendations

A majority of women who become justice-involved have experienced trauma, including childhood and adult victimiisation, sexual abuse, involvement with child protection, and family violence.[16]

These experiences of gendered violence can drive women to engage in offending behaviour, for example, self-medicating with illicit drugs or resisting violence through physical force, resulting inand being misidentified as the predominant aggressor. These experiences place women at risk of criminalisation and create barriers to accessing services that can respond to trauma or complex needs.[17]

While the implementation of the Royal Commission into Family Violence recommendations have improved both specialist and mainstream services responses to victim survivors of family violence, there is a need for increased resourcing of primary prevention and long-term recovery supports.

Further to these recommendations, VCOSS is a member of the Smart Justice for Women Coalition and we endorse the recommendations it has made to this Inquiry to address the overrepresentation of women in Victoria’s criminal justice system.

Recommendations

People with disabilities are overrepresented in the criminal justice system, as victims, accused persons, defendants and witnesses.

The Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability heard that overrepresentation can be attributed to issues including:

People with disabilities also experience the “criminalisation of disability”, when conduct associated with people’s impairment, health condition or trauma are interpreted as difficult or defiant behaviours, leading to disproportionate interactions with police.[18]

Currently, there is no consistent approach to screening for people with disabilities at any stage of criminal procedure. Implementing a systemic approach to disability screening would inform more appropriate responses in policing, courts and prison. In particular, screening for disability provides an opportunity to engage community-based services as a more appropriate alternative to custody.[19]

The Victorian Government has implemented a Communication Intermediaries Pilot Program trial to assist victims of crime and witnesses with communication difficulties to give evidence to police and in court. While there have been some constraints with implementing this program remotely during the COVID-19 restrictions, Government should commit to completing the trial, and consider making the program available in all courts if successful.

recommendations

Victoria Police are reluctant to collect and release data on policing practices between different cultural or linguistically diverse groups.[20] Despite this, a significant body of evidence indicates that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are less likely to be provided with opportunities for diversion[21], more likely to be charged with public nuisance offences[22] and more likely to be targeted for offences such as being drunk in a public place[23].

A commitment to addressing systemic racism and ending impunity is crucial for moving towards a more just, equal and safe future for everyone. Discrimination and racism in policing practices, particularly in relation to, must be acknowledged and immediately addressed, and any reforms must be led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Recommendations

Currently, children as young as 10 can and do experience the full force of the criminal justice system.

When a child demonstrates anti-social or offending behaviour, an opportunity emerges for appropriate social supports to make a positive intervention in their life. Responses to child offending should:

Supports should be provided across an integrated continuum, prioritising and investing in prevention, early intervention and therapeutic and restorative justice as the most effective ways to respond to child and young offending/re-offending.

VCOSS believes that a system-wide response is required to tackle the systemic failings which underpin children’s involvement in the justice system. There is a need to better integrate policies and practices across child and family welfare, education, disability, health, police, legal and youth justice systems. Community should be involved in design and implementation, including Aboriginal and culturally diverse communities. This would increase the effectiveness of interventions by addressing community-identified problems, drawing on existing community strengths and resources, and being culturally responsive.[24]

Reorienting responses to child offending from punitive to therapeutic will require a significant boost in funding for effective programs. This can be achieved by adopting a framework that ensures equitable funding for programs across the continuum and better integration between systems. Presently, a significant barrier to protecting children from offending and reoffending is the lack of access to an appropriate program that meets their needs and is a proportionate response to the nature of their offending behaviour.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are over-imprisoned, making up about 60 per cent of the young children in youth justice facilities, despite being only about 5 per cent of the population (aged 10-17).[25] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to experience the ongoing impacts of colonisation, trauma, dispossession and racism. The over-incarceration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people is both a result of this ongoing trauma and exacerbates it.

In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, the planning, design and implementation of alternative justice responses should be community-led.

Further to our recommendations, VCOSS is a member of the Smart Justice for Young People Coalition and we endorse the recommendations it has made to this Inquiry to address the overrepresentation of children and young people in Victoria’s criminal justice system.

Recommendations

A 2012 literature review on the ‘victim-offender overlap’ identified studies reporting that more than half of victims of crime become offenders and vice versa.[26] This is a higher rate for women in the justice system, where between 70 to 90 per cent of women in prison are victim-survivors of family violence, sexual abuse or child abuse.

Supporting victims to recover in a way that is therapeutic and does not contribute to further trauma can prevent victims from becoming perpetrators.

Since the 2018 review of the Victims of Crime Assistance Act, some improvements have been made to victim support, including the establishment of a welcome new financial assistance scheme. However, victims continue to experience barriers to accessing support, due to the complexity in navigating the range of assistance options available.

As the Centre for Innovative Justice noted in their Victim Services Review, victims of crime should be supported to find and access assistance and be empowered to make informed decisions about which assistance would meet their needs. This could be achieved by establishing a more coherent and effective Victim Support System, comprising coordination of existing victim services into a single model that victims can step through as their needs change over time, as well as improved access through digital service delivery and improved integration of victim assistance in existing community services, [27] including community legal centres.

Recommendations

Over the past decade, a range of reforms to Victoria’s criminal law have been implemented that increase punitive approaches to offending and restrict judicial discretion:

These reforms have not made our community safer. The Bail Act 1997(Vic) reforms introduced a reverse onus test, intended to capture serious, violence offenders. Instead, the changes have had a disproportionate impact on women who have engaged in low-level, non-violent offending, in particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, and people experiencing homelessness, and has resulting in the alarming increase in the number of people incarcerated on unsentenced remand. Consistent with a long-standing recommendation by the Victorian Law Reform Commission, the Victorian Government should repeal the reverse onus test and replace it with a presumption in favour of bail unless there is a specific and immediate risk to the safety of another person.

Rehabilitation should be prioritised as the primary factor for any sentencing decision. The sentencing hierarchy should also be reviewed to provide additional options for community-based treated and rehabilitation. VCOSS supports the recommendation by the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service (VALS) for a new requirement that courts take into consideration the unique systemic and background factors affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The Victorian Government should reinstate the presumption that parole would be granted at the earliest eligibility date unless there was a compelling reason why this should not occur. Further, Adult Parole Board decisions should be more transparent and subject to public accountability.

The criminogenic effects and other long-term trauma and disadvantage associated with justice system involvement is well documented.

Until prevention and early intervention are prioritised and adequately resourced, change will be required to reduce harm for those that do encounter the criminal justice system. We acknowledge the inherent tension between therapeutic approaches and the carceral nature of the criminal justice system. Despite this, steps can be taken to make contact with the justice system a more positive and less harmful intervention in people’s lives.

Recommendations

As previously discussed, many people who encounter the justice system have experienced disadvantage, vulnerability and trauma. All criminal justice system personnel – including police, courts and service providers – must have capability to provide safe and respectful responses to those they interact with.

The Blue Knot Foundation suggests that trauma-informed practice could be incorporated into the justice system by ensuring all personnel have training to apply the following core principles[29]:

Additionally, justice system personnel should be required to regularly undertake training in:

Community organisations have deep and broad knowledge of the challenges and barriers faced by people who may be vulnerable or experiencing disadvantage and justice-involved, and have established, trusted relationships with community. We stand ready to assist justice system workforces to develop their skills in this area.

The capacity of judges and magistrates to ensure fair hearing and safety for alleged offenders can also be improved by establishing a judicial diversity strategy, as the UK recently introduced.

As the former High Court Justice Michael McHugh said – “when a court is socially and culturally homogenous, it is less likely to command public confidence in the impartiality of the institution.”[30]

There is strong interest amongst VCOSS members in the Victorian Government developing a strategy to increase diversity amongst judges and magistrates – including cultural and linguistic diversity, a range of gender identities, diversity of lived experience and personal background, and diversity of legal experience, especially by appointing more judges and magistrates from the community legal sector – to increase trust in the institution, and to ensure differing perspectives across the system. VCOSS encourages the Victorian Government to consider this positive proposal, and to explore it further with communities through a public consultation process.

Recommendations

The criminalisation of people who are vulnerable or disadvantaged is inextricably linked to police practice.

The decriminalisation of public drunkenness and the implementation of a new health-based model demonstrates an approach that prioritises the health and safety of Victorians and is a welcome shift away from a reliance on punitive, police-led responses. The Victorian Government should commit to the adoption and implementation of a health-based, harm-minimisation response to drug use, and explore further opportunities for drug decriminalisation.

Victoria Police can also incorporate more community policing approaches into police practice, including establishing better connections with local community organisations.[31] For example, VCOSS members acknowledge good outcomes for community when police use the Police, Ambulance and Clinical Early Response (PACER) model in first responses. In this model, police have wide discretion to draw on clinicians – including social workers, lawyers and advocates – when first attending callouts for incidences involving public nuisance, drug and alcohol use and mental health episodes. However, our members note that due to this wide discretion, there are inconsistencies in the use of the model. Itrelies greatly on individual police members’ relationships with local service providers.

Victoria Police members should be required to increase their knowledge of and relationships with local service providers. Further, they should make better use of models like PACER and increase their use of both warm referrals and e-referrals to engage services providers in their responses.

Without adequate training to engage with vulnerable members of the community (as discussed in the previous section), poor justice outcomes may emerge for those who are subject to over-policing and misuse of police power. Police who do abuse the trust of Victorians and undermine the integrity of the justice system must be held accountable. Existing accountability mechanisms are failing to change systemic behaviour or build community confidence in police. The Victorian Government should implement a system of independent investigation of police misconduct.

Recommendations

The Victorian Government can invest in more specialist problem-solving and diversionary courts to reduce crime and prisoner numbers. Where traditional, adversarial approaches fail, problem-solving courts deal with the behaviours causing offending, and they work: Drug Court recidivism rates are 34 per cent lower.[32] The Victorian Drug Court should be expanded to keep people out of prison through treatment and rehabilitation. Similarly, the Neighbourhood Justice Centre has significantly improved community order compliance and reduced recidivism.[33] Offenders appearing before the Neighbourhood Justice Centre (NJC) are less likely to reoffend and has cut Yarra area crime rates by 12 per cent in two years.

The establishment of the Specialist Family Violence Court in Shepparton and the expansion of the Drug Court to Shepparton and Ballarat are welcome initiatives to ensure access to justice and problem-solving approaches for regional and rural Victorians.

The Victorian Government can use data and population health planning to prioritise responses in areas across Victoria with most need. For example, despite having one of the highest rates of family violence in Melbourne, there is not a Family Violence Court in or near Broadmeadows. Data-driven planning would also inform the resourcing and integration of specific community services that would assist the Court response.

Recommendations

The current approach to managing people exiting prison means that people who leave prison are punished well beyond their sentence. This is indicated by:

Better outcomes for people leaving prison begins with access to appropriate health and social supports in prison. Currently, there is no publicly available, linked data on people who move through Victoria’s prisons, which constrains efforts to make system improvements. As Coroner Hawkins recommended in a recent investigation,[34] the Victorian Government should make this data available to support reform.

Despite a high prevalence of people with disabilities in Victoria’s prisons, there are barriers to accessing the National Disability Insurance Scheme and necessary disability supports. The Victorian Government should improve the interface between the NDIS and justice system across Victorian prisons, and better co-ordinate and integrate service systems to ensure all people with disability are fully supported while in prison and when transitioning out of prison.

Further, the Government should develop a protocol to identify whether people entering prison are NDIS participants, or are potentially eligible to be participants, and facilitate access requests at the earliest opportunity, in partnership with the Commonwealth government and NDIA.

Corrections Victoria offer a range of transitional planning and support programs, including through Assessment and Transition Coordinators and the ReLink, ReConnect and ReStart programs. These programs provide vital transitional planning and support to people exiting prison and provide an opportunity to understand and map a person’s needs in relation to housing and other supports upon release.

However, only 20 per cent of people leaving prison have access to any supports from Corrections Victoria pre- and post-release.[35] Further, there are significant gaps in discharge planning, support and continuity of care when people are released that prevent successful reintegration and recovery.

In Norway, people leaving prison are provided with a range of supports under the “Reintegration Guarantee”, which includes support to obtain housing, work, school, health care debt counselling, and includes a framework to coordinate all government and community stakeholders involved in providing supports.[36] The success of this model is demonstrated by their status of having one of the lowest recidivism rates in the world, at 20 per cent,[37] compared to 44 per cent in Victoria.[38]

The Victorian Government should establish a program modelled on the Norwegian “Reintegration Guarantee”, that incorporates the following principles:

VCOSS supports Coroner Hawkins’ recommendation that the Department of Health adopt formal responsibility for improving the health outcomes of people leaving prison and should coordinate housing and other social supports with Department of Families, Fairness and Housing.

[1] Victorian Ombudsman, Investigation into the Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Prisoners in Victoria, September 2015, p 2.

[2] VCOSS, Every suburb, every town: mapping poverty in Victoria, November 2018

[3] VCOSS, A secure and decent living – VCOSS Submission to the Senate Inquiry into Job Security, April 2022.

[4] KPMG, Maranguka Justice Reinvestment Project – Impact assessment, November 2018.

[5] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, The health of Australia’s prisoners 2018, May 2019, p viii.

[6] Victorian Ombudsman, Investigation into the rehabilitation and reintegration of prisoners in Victoria, September 2015, p 2.

[7] Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Final Report Volume 1: A new approach to mental health and wellbeing in Victoria, February 2021, p 355.

[8] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, The health of Australia’s prisoners 2018, May 2019, p vi.

[9] Ibid p vii.

[10] Ibid p vii.

[11] Ibid p 77.

[12] Victorian Ombudsman, Investigation into the rehabilitation and reintegration of prisoners in Victoria, September 2015, p87.

[13] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, The health of Australia’s prisoners 2018, May 2019, p viii.

[14] Ibid, p vi.

[15] Parliament of Victoria, Inquiry into the use of Cannabis in Victoria – Final Report, August 2021, p 78.

[16] Centre for Innovative Justice, Leaving Custody Behind – Issues Paper, July 2021, p 23.

[17] Ibid, p 24.

[18] Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability, Overview of responses to the Criminal Justice System Issues Paper, December 2020, p 3.

[19] Australian Human Rights Commission, People with disability and the criminal Justice System, 20 March 2020, p 30.

[20] M McGowan and C Knaus, ‘Essentially a cover-up’: why it’s so hard to measure the over-policing of Indigenous Australians, The Guardian, 13 June 2020.

[21] N Papalia, Disparities in Criminal Justice System Responses to First-Time Juvenile Offenders According to Indigenous Status, May 2019.

[22] Sentencing Council Queensland, Connecting the Dots, March 2021.

[23] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Prisoners in Australia (2018) Table 1.

[24] K Richards, L Rosevear and R Gilbert, Promising interventions for reducing indigenous juvenile offending: Brief 1, Australian Institute of Criminology, March 2011.

[25] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Youth detention population in Australia 2018, December 2018.

[26] W G Jennings et al, On the overlap between victimisation and offending: A review of the literature, Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 2012, p 17.

[27] Centre for Innovative Justice, Strengthening Victoria’s Victim Support System: Victim Services Review, November 2020, p 14.

[28] Victorian Government, ‘Record Recruitment Drive Boosts Police Numbers’, Media release, 15 July 2019 https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/record-recruitment-drive-boosts-police-numbers/

[29] Blue Knot Foundation, Trauma and the law: Applying trauma-informed practice to legal and judicial contexts, 2016, p 5.

[30] Former High Court Justice Michael McHugh in a speech to the Western Australian Law Society, 2004.

[31] M Segrave and J Ratcliffe, Community Policing: A descriptive overview, March 2004.

[32] KPMG, Magistrates’ Court of Victoria, Evaluation of the Drug Court of Victoria, 2014, p. 4.

[33] S Ross, Evaluating neighbourhood justice: Measuring and attributing outcomes for a community justice program, 2015, p. 5.

[34] Coroners Court of Victoria, Finding into death without inquest (Shae Harry Paszkiewicz), February 2021.

[35]Ibid.

[36] Confederation of European Probation, Norwegian Reintegration Guarantee aims to provide ex-prisoners the right tools for resocialization.

[38] Sentencing Advisory Council, Released prisoner returning to prison, 2020.

[37] BBC, How Norway turns criminals into good neighbours, July 2019.

(1/1) ErrorException |

|---|

| in download-attachment.php line 6 |

| at RegisterExceptionHandler->handleError(8, 'Trying to access array offset on value of type bool', '/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/partials/download-attachment.php', 6, array('slug' => 'partials/download-attachment', 'args' => null, 'return' => false, 'wp_query' => object(WP_Query), 'templates' => array('partials/download-attachment.php'), 'template_file' => '/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/partials/download-attachment.php', 'page' => 0, 'year' => 2021, 'monthnum' => 9, 'name' => 'strong-communities-are-safe-communities', 'category_name' => 'justice-and-human-rights', 'error' => '', 'm' => '', 'p' => 0, 'post_parent' => '', 'subpost' => '', 'subpost_id' => '', 'attachment' => '', 'attachment_id' => 0, 'pagename' => '', 'page_id' => 0, 'second' => '', 'minute' => '', 'hour' => '', 'day' => 0, 'w' => 0, 'tag' => '', 'cat' => '', 'tag_id' => '', 'author' => '', 'author_name' => '', 'feed' => '', 'tb' => '', 'paged' => 0, 'meta_key' => '', 'meta_value' => '', 'preview' => '', 's' => '', 'sentence' => '', 'title' => '', 'fields' => array(array('file' => false), array('file' => false)), 'menu_order' => '', 'embed' => '', 'category__in' => array(), 'category__not_in' => array(), 'category__and' => array(), 'post__in' => array(), 'post__not_in' => array(), 'post_name__in' => array(), 'tag__in' => array(), 'tag__not_in' => array(), 'tag__and' => array(), 'tag_slug__in' => array(), 'tag_slug__and' => array(), 'post_parent__in' => array(), 'post_parent__not_in' => array(), 'author__in' => array(), 'author__not_in' => array(), 'search_columns' => array(), 'ignore_sticky_posts' => false, 'suppress_filters' => false, 'cache_results' => true, 'update_post_term_cache' => true, 'update_menu_item_cache' => false, 'lazy_load_term_meta' => true, 'update_post_meta_cache' => true, 'post_type' => '', 'posts_per_page' => 30, 'nopaging' => false, 'comments_per_page' => '50', 'no_found_rows' => false, 'order' => 'DESC', 'field' => array('file' => false), 'file' => false))in download-attachment.php line 6 |

| at require('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/partials/download-attachment.php')in Core.php line 74 |

| at Core::get_template_view('partials/download-attachment')in single-post-content.php line 12 |

| at require('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/partials/single-post-content.php')in Core.php line 74 |

| at Core::get_template_view('partials/single-post-content', null, true)in single-post.php line 21 |

| at include('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php')in WordPressControllersServiceProvider.php line 23 |

| at WordPressControllersServiceProvider->handleTemplateInclude('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php')in class-wp-hook.php line 324 |

| at WP_Hook->apply_filters('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php', array('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php'))in plugin.php line 205 |

| at apply_filters('template_include', '/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-content/themes/vcoss/single-post.php')in template-loader.php line 104 |

| at require_once('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-includes/template-loader.php')in wp-blog-header.php line 19 |

| at require('/home/vcossorg/public_html/wp-blog-header.php')in index.php line 17 |