Image: Margaret Simons (Twitter @MargaretSimons)

Back into poverty Budget

Back into poverty

VCOSS welcomes the opportunity to provide input to the Senate Community Affairs Legislative Committee on the Social Service Legislative Amendment (Strengthening Income Support) Bill.

The amendment proposes an increase to the permanent rate of JobSeeker of about $25 per fortnight. That will not be enough to keep people out of poverty and will have long-term impacts on people’s health, wellbeing and prospects of employment.

To alleviate poverty, VCOSS strongly advocates the government increase the rate from the proposed $44 per day to at least $65 per day and commit to ongoing indexation of payments in line with wage movements at least twice per year.

The rate of JobSeeker should raise people above the poverty line

13 per cent of Victorians currently live in poverty.[1] Poverty exists in every Victorian community, with rates highest in regional and rural Victoria. Poverty stops people living healthy and happy lives. It can lead to isolation, to children disengaging from school, and to poor physical and mental health.

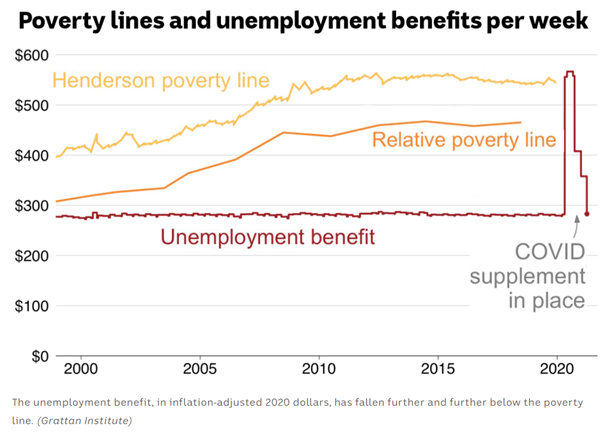

Receiving JobSeeker is the biggest risk factor for living in poverty. In January 2021 there were approximately 333,000 JobSeeker recipients in Victoria[2] or approximately 10 per cent of the Victorian labour force of 3.4 million people.

The proposed increase to the base rate of JobSeeker will leave these Victorians living well below the poverty line. For example, a single person without children will be $166 per fortnight short of the poverty line.

The Coronavirus Supplement lifted people out of poverty

The Australia Institute estimates that 425,000 Australians were lifted out of poverty due to the Coronavirus Supplement alone.[3] JobSeeker recipients told VCOSS that when they received the Coronavirus Supplement they were able to buy fresh food, eat three meals a day, and pay their bills for the first time.

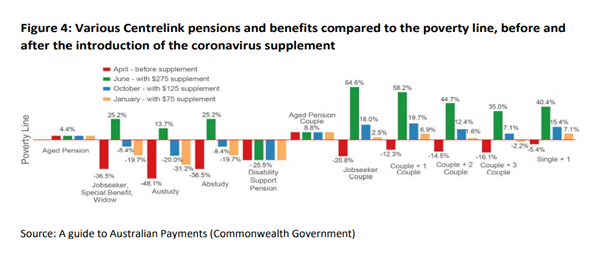

All income support recipients, excluding disability support pensioners, “found themselves moving from incomes well below the poverty line to incomes above it, sometimes substantially so” as a result of the Coronavirus Supplement.[4]

People in households with two partners unemployed were the biggest beneficiaries, seeing their incomes rise collectively from between 10 to 20 per cent below the poverty line to between 35 per cent and 65 per cent above it.[5] This resulted in a rise in living standards for many JobSeeker recipients.

The proposed JobSeeker rate will send many families back to a life of poverty, forced to choose between medical care or energy bills, food or school supplies.

It’s hard to get a job when you live in poverty

Getting people back into work, post-COVID-19, is a worthy goal. But an inadequate rate of income support actually makes it harder for people to get work. It is more difficult to travel to interviews, pay for childcare, afford job-searching resources like the internet and devices, or look after your health, making the job hunt virtually impossible.

The impacts of an inadequate rate of JobSeeker may be particularly acute in Victoria. Victoria experienced a more prolonged COVID-19 related lockdown than any other Australian state or territory. As a result, Victorians have been hit harder by job losses than people living in other states and territories.

For example, between the week ending 14 March 2020 and the week ending 30 January 2021, payroll jobs in Victoria decreased by 3.7 per cent, the largest decrease out of all the states and territories.[6] Victoria’s unemployment rate is 6.3 per cent – the third highest in the nation, behind Queensland and South Australia.[7]

The system should enable and empower people to work and participate in society, and set them up to succeed. Overly strict and punishing compliance regimes may do more harm than good. Forcing people to apply for inappropriate jobs, or those they are not qualified for, to meet unreasonable mutual obligations does nothing to help people move into decent and secure employment.

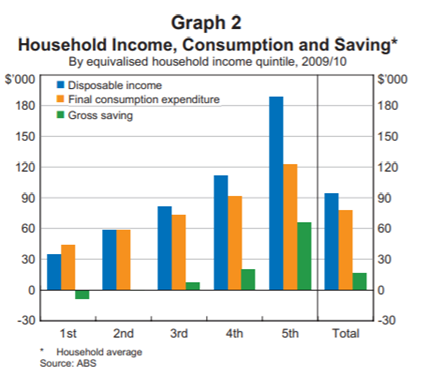

As well as making it harder for people to find jobs, the decision will likely have economic impacts. Most people who received the full Coronavirus Supplement last year reported they spent it on household bills, supplies and groceries. As the diagram shows, the lowest income quintile are in fact “dis-savers”, spending more than what they earn.[8]

That’s economic stimulus during a time when many Australian businesses are struggling. If the rate is low, people will have less money to spend on basics in local economies.

Demand for community services will increase if JobSeeker is inadequate

The inadequate rate of JobSeeker will place additional pressure on community service organisations. Prior to the pandemic, demand in the community services sector was already high and growing. Three-fifths of community sector staff surveyed in 2019 reported the number of clients that their service was unable to support had grown in the last twelve months.[9]

Many community organisations are reporting increased demand from people affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.[10] This includes a large group of Victorians who have never needed support from the community sector before.[11]

Rates of financial hardship are growing. Many Victorians are already accessing credit, savings and superannuation to spend on essential goods, and are worried about their ability to pay bills.[12]

When the JobSeeker rate is cut, and other COVID-19 measures end (like the evictions moratorium), there will be further increases in demand for Government and community services. This will mean stretched services, exhausted workers, longer waiting lists and people unable to get help when they need it.

To discuss this submission further, please contact Brooke McKail, Manager Policy and Research on brooke.mckail@vcoss.org.au

[1] VCOSS, Every suburb, every town: mapping poverty in Victoria, November 2018.

[2] Department of Social Services, JobSeeker Payment and Youth Allowance Recipient – month profile, January 2021.

[3] Grudnoff, M, Poverty in the age of coronavirus. The impact of the JobSeeker coronavirus

supplement on poverty, Australia Institute Discussion Paper, Australia Institute, July 2020.

[4] Dr David Hayward, Liss Ralston and Hayden Raysmith, Social policy during the coronavirus recession: a fairytale with an

unhappy ending? A case study of Victoria, VCOSS Occasional Paper, 2020.

[5] Ibid.

[6] ABS, Weekly Payroll Jobs and Wages in Australia, 13 February 2021

[7] ABS, Labour Force, Australia, 18 February 2021,

[8] A Beech, R Dollman, R Finlay and G La Cava, The Distribution of Household Spending in Australia, Reserve Bank of Australia, March 2014.

[9] ACOSS, Demand for Community Services Snapshot, December 2019.

[10] VCOSS and FSSI, Stories into Evidence: Covid-19 adaptations in the Victorian community services sector, 2020, p.7.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Consumer Policy Research Centre, COVID-19 and Consumers: from crisis to recovery; Monthly Insights Report: October – December 2020, 2020.